Introduction

The Müller-Brown potential serves as the original “adversarial example” for optimization algorithms.

Designed in 1979 to break naive path-finding methods, this deceptively simple 2D surface features deep minima, high barriers, and tricky saddle points. For nearly five decades, it has served as a ground-truth benchmark for computational chemistry.

Today, it finds new life as a testbed for machine learning. In the 1970s, chemists struggled to find transition states, saddle points where standard gradient descent fails catastrophically. Modern machine learning engineers face a strikingly similar challenge: escaping saddle points in high-dimensional loss landscapes. The Müller-Brown potential was the original stress test for these algorithms, and it remains a perfect, low-cost sandbox for benchmarking modern optimizers.

Whether you’re training neural network potentials or benchmarking reinforcement learning agents for exploration, the Müller-Brown potential offers a fast, noise-free, and mathematically exact environment.

In this guide, we’ll implement a high-performance version in PyTorch, tackling the engineering trade-offs between analytical derivatives vs. Autograd, and demonstrating how to achieve 3-10x speedups via JIT compilation.

The Problem: Finding Saddle Points in the 1970s

In the 1970s, finding energy minima was straightforward: follow the gradient downhill. But finding transition states proved much more challenging. These saddle points are maxima along the reaction coordinate but minima in all other directions, like standing at the top of a mountain pass.

Standard first-order optimizers, whether 1970s simplex methods or modern SGD and Adam, are designed to minimize loss functions blindly. Point them at a saddle point, and they slide into the nearest valley. The gradients vanish or point in misleading directions. Specialized algorithms were needed to navigate this mixed landscape of ups and downs.

The computational reality made this worse. Early quantum chemistry programs like ATMOL and Gaussian made energy calculations possible, but each computation was expensive. Gradients required even more resources, and second derivatives were rarely computed.

This created a catch-22: sophisticated algorithms were needed to find saddle points, but researchers couldn’t afford to test them on real molecular systems. Every calculation represented a major investment of time and computational resources.

Müller and Brown’s Solution

Müller and Brown’s insight was to create a simple analytical test function that captured the essential difficulties of real chemical systems without the computational cost. Their potential offered three key advantages:

- Negligible computational cost - Evaluate millions of points instantly

- Analytical derivatives - Exact gradients and Hessians available immediately

- Realistic challenges - Multiple minima, saddle points, and curved pathways

The clever part was the deliberate design to break naive approaches. Early methods often assumed linear paths between reactants and products. The Müller-Brown potential has a curved minimum energy path that punishes this assumption. Try to take shortcuts, and algorithms climb over high-energy barriers.

The Mathematical Foundation

The Müller-Brown potential combines four two-dimensional Gaussian functions:

$$V(x,y) = \sum_{k=1}^{4} A_k \exp\left[a_k(x-x_k^0)^2 + b_k(x-x_k^0)(y-y_k^0) + c_k(y-y_k^0)^2\right]$$

Each Gaussian contributes a different “bump” or “well” to the landscape. The parameters control amplitude ($A_k$), width, orientation, and center position.

The Standard Parameters

The specific parameter values that define the canonical Müller-Brown surface are:

| k | $A_k$ | $a_k$ | $b_k$ | $c_k$ | $x_k^0$ | $y_k^0$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -200 | -1 | 0 | -10 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | -100 | -1 | 0 | -10 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 3 | -170 | -6.5 | 11 | -6.5 | -0.5 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 15 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | -1 | 1 |

Notice that the first three terms have negative amplitudes (creating energy wells), while the fourth has a positive amplitude (creating a barrier). The cross-term $b_k$ in the third Gaussian creates the tilted orientation that gives the surface its characteristic curved pathways.

View Interactive Müller-Brown Potential Energy Surface →

The Resulting Landscape

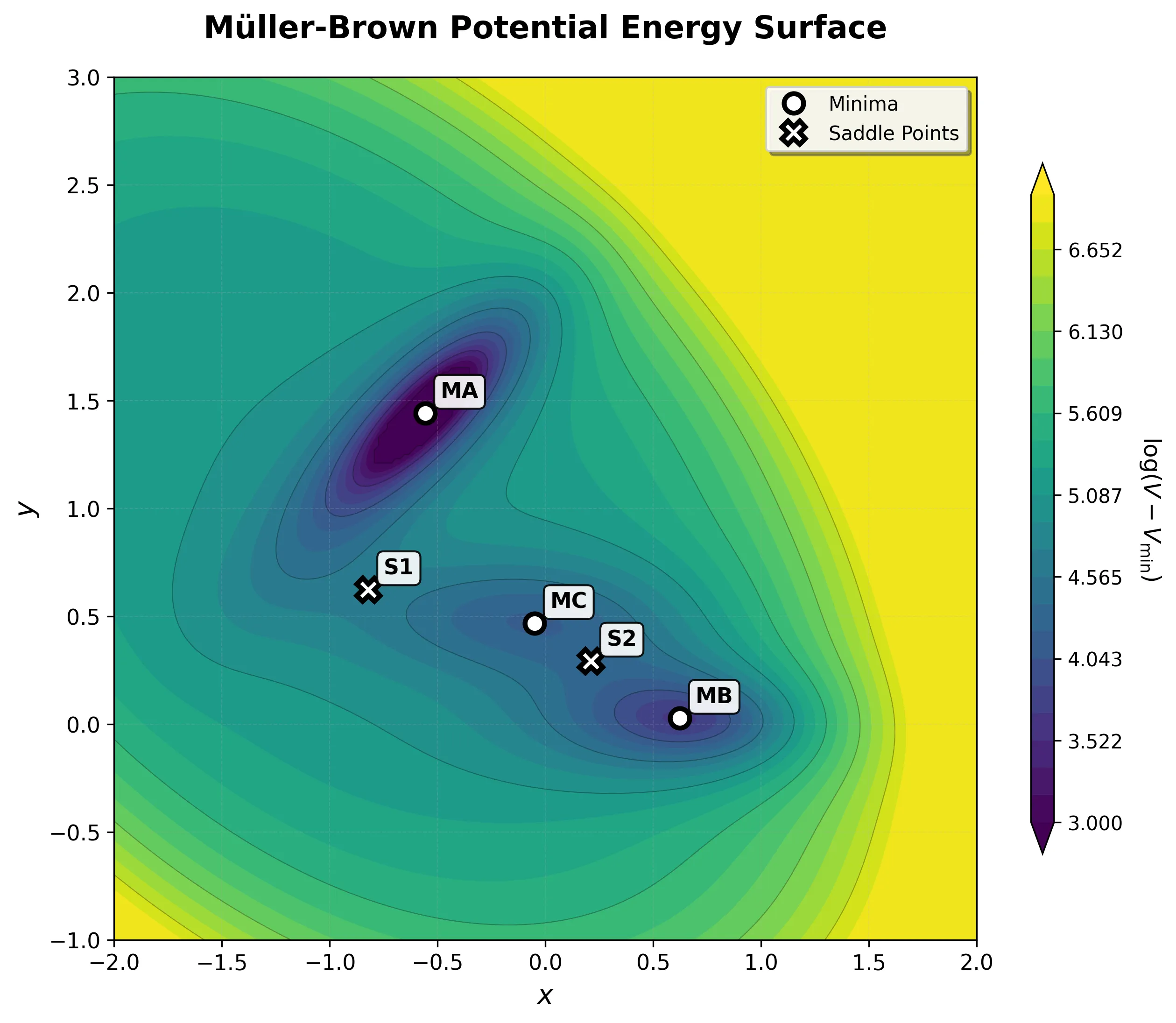

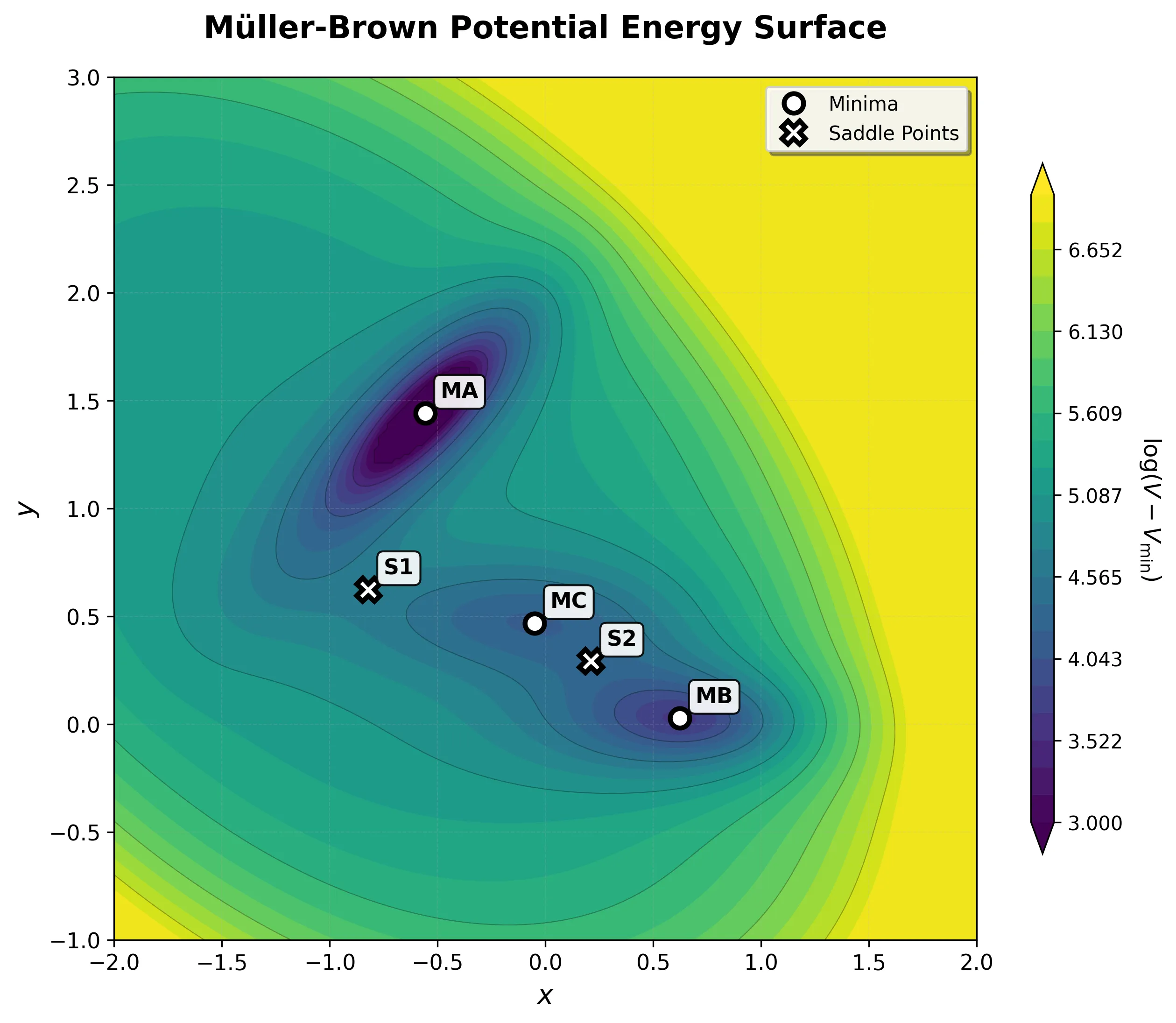

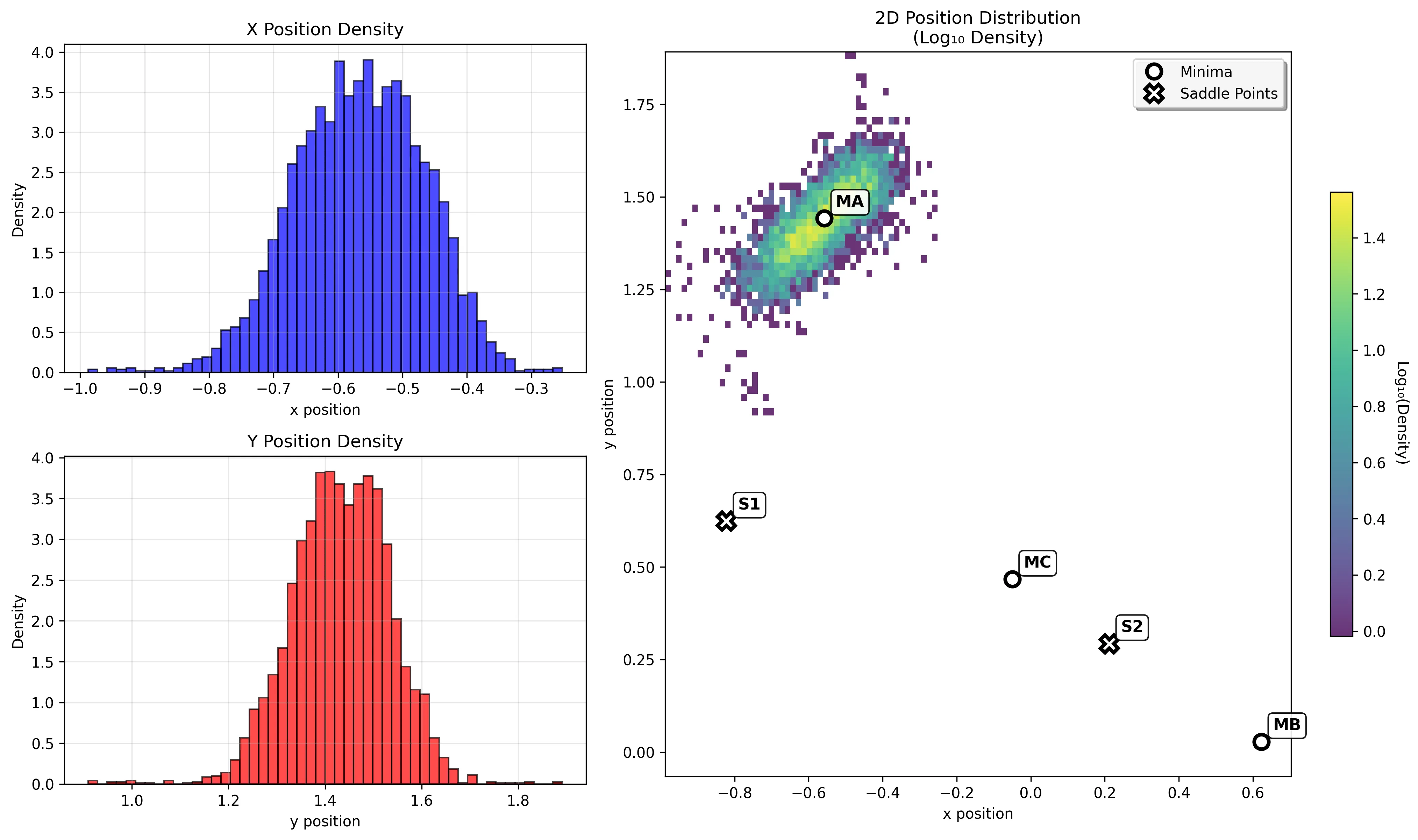

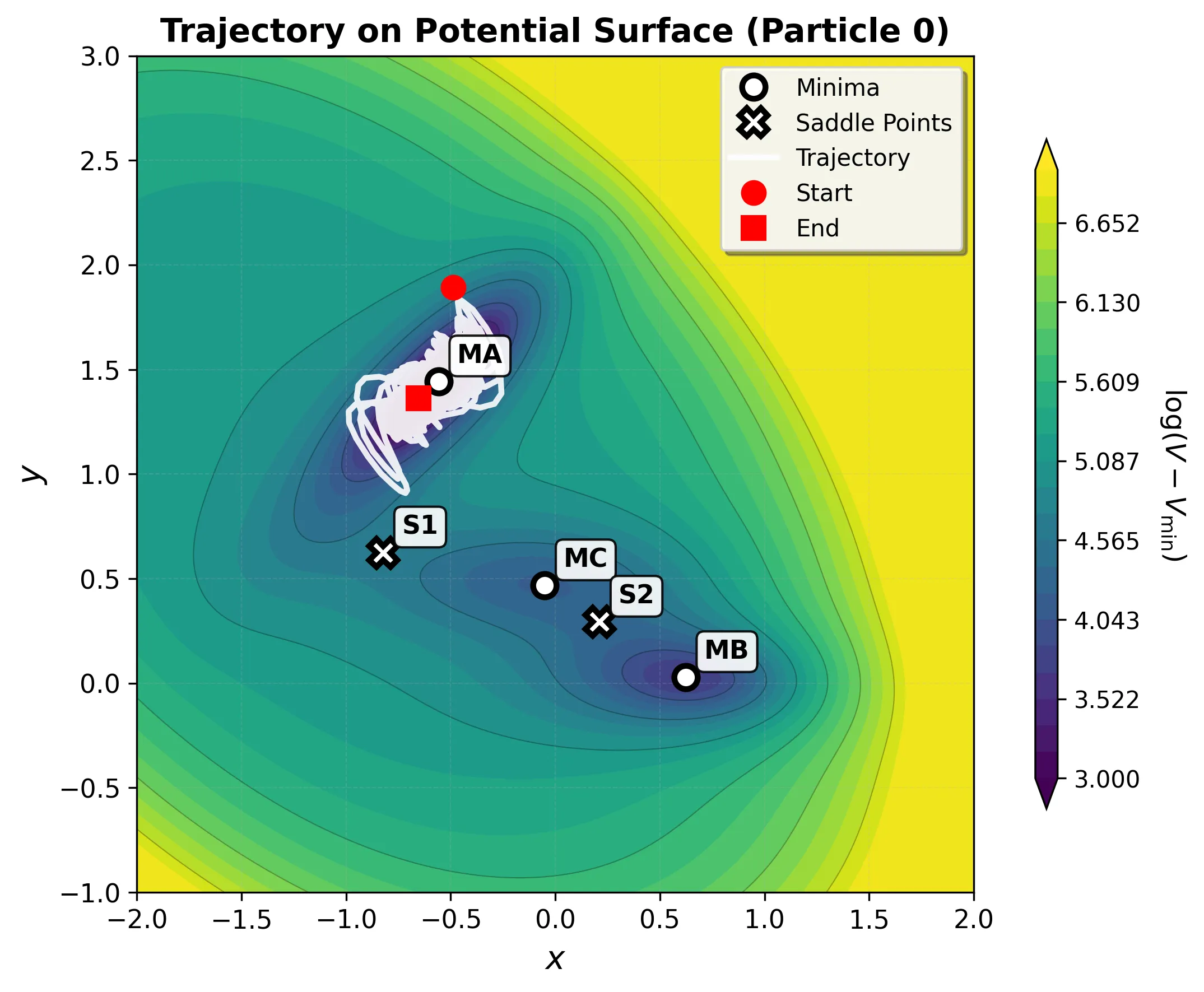

This simple formula creates a surprisingly rich topography with exactly the features needed to challenge optimization algorithms:

| Stationary Point | Coordinates | Energy | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| MA (Reactant) | (-0.558, 1.442) | -146.70 | Deep minimum |

| MC (Intermediate) | (-0.050, 0.467) | -80.77 | Shallow minimum |

| MB (Product) | (0.623, 0.028) | -108.17 | Medium minimum |

| S1 | (-0.822, 0.624) | -40.66 | First saddle point |

| S2 | (0.212, 0.293) | -46.62 | Second saddle point |

The Key Challenge: Curved Pathways

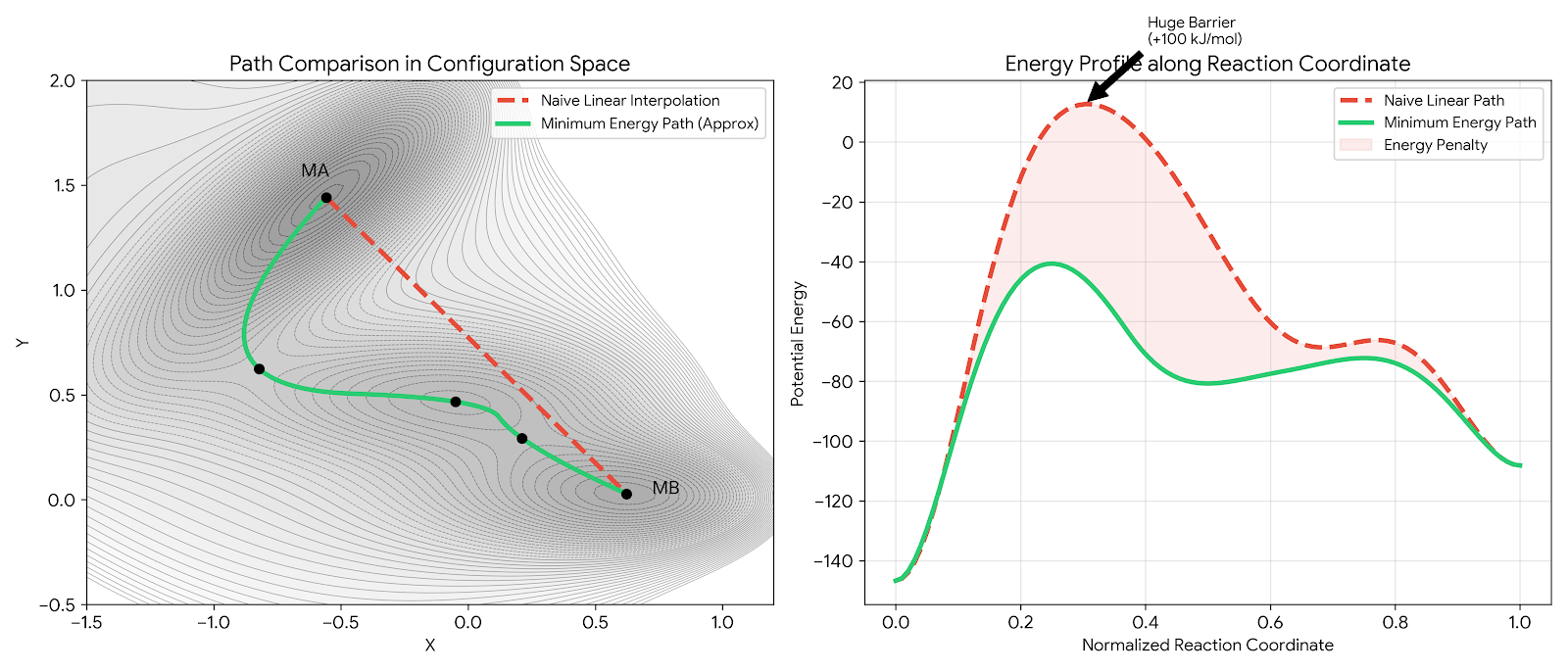

The path from the deep reactant minimum (MA) to the product minimum (MB) doesn’t go directly over a single barrier. Instead, it follows a curved route:

- MA → S1 → MC: First transition over a lower barrier into an intermediate basin

- MC → S2 → MB: Second transition over a slightly higher barrier to the product

This two-step pathway breaks linear interpolation methods. Algorithms that draw a straight line from reactant to product miss both the intermediate minimum and the correct transition states, climbing over much higher energy regions instead.

The energy profile comparison makes the failure mode concrete. A naive optimizer following the red dashed path would encounter a barrier roughly 100 kJ/mol higher than necessary, an insurmountable wall in molecular terms. The green minimum energy path navigates through the valleys, passing through the intermediate basin MC and crossing only the low-lying saddle points S1 and S2.

Why It Works as a Benchmark

The Müller-Brown potential has served as a computational chemistry benchmark for over four decades because of four key characteristics:

Low dimensionality: As a 2D surface, you can visualize the entire landscape and see exactly why algorithms succeed or fail.

Analytical form: Energy and gradient calculations cost virtually nothing, enabling exhaustive testing impossible with quantum mechanical surfaces.

Non-trivial topology: The curved minimum energy path and shallow intermediate minimum challenge sophisticated methods while remaining manageable.

Known ground truth: All minima and saddle points are precisely known, providing unambiguous success metrics.

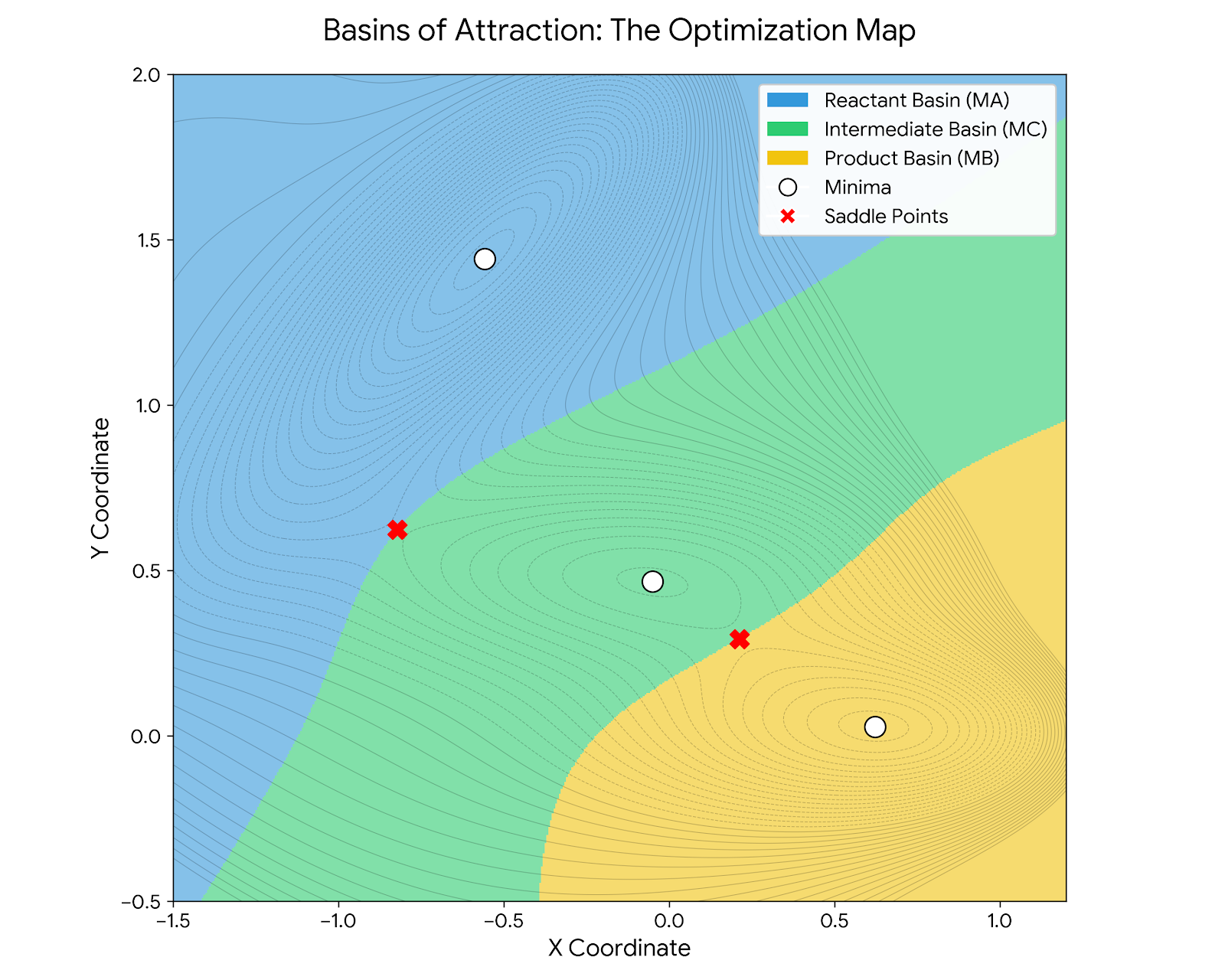

This basin map reveals why the Müller-Brown potential is such an effective benchmark. Standard gradient descent from any point in the blue region inevitably falls into the deep MA minimum; from yellow, into MB. The saddle points S1 and S2 lie exactly on the boundaries between basins, infinitesimally perturbing an optimizer at these points sends it tumbling into different valleys. Finding these saddle points requires algorithms that identify and stabilize at these boundary regions.

What makes this particularly valuable is the contrast with other classic potentials. While the Lennard-Jones potential[^jones1931] serves as the benchmark for equilibrium properties with its single energy minimum, Müller-Brown explicitly models reactive landscapes. Its multiple minima and connecting barriers make it the testing ground for algorithms that find reaction paths, the methods that reveal how chemistry actually happens.

Applications Across Decades

The potential has evolved with the field’s changing focus:

1980s-1990s: Testing path-finding methods like Nudged Elastic Band (NEB)[^henkelman2000], which creates discrete representations of reaction pathways and optimizes them to find minimum energy paths.

2000s-2010s: Validating Transition Path Sampling (TPS) methods[^dellago1998] that harvest statistical ensembles of reactive trajectories.

2020s: Benchmarking machine learning models and generative approaches that learn to sample transition paths or approximate potential energy surfaces.

Modern Applications in Machine Learning

The rise of machine learning has given the Müller-Brown potential renewed purpose. Modern Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)[^behler2007][^smith2017] aim to bridge the gap between quantum mechanical accuracy and classical force field efficiency by training flexible models on expensive quantum chemistry data.

This creates a benchmarking challenge: with countless ML architectures available, how do you objectively compare them? The Müller-Brown potential provides an ideal solution, an exactly known potential energy surface that can generate unlimited, noise-free training data.

This enables researchers to ask fundamental questions:

- How well does a given architecture learn complex, curved surfaces?

- How many training points are needed for acceptable accuracy?

- How does the model behave when extrapolating beyond training data?

- Can it correctly identify minima and saddle points?

The potential has evolved from being a simple model system to serving as a metrological standard: a ruler against which AI learning capacity is measured. Any prediction error is purely due to model limitations, not data quality issues.

Beyond static benchmarking, a PyTorch implementation unlocks differentiable simulation. Because the potential, forces, and integrator are all differentiable tensor operations, gradients can be backpropagated through time (via the trajectory) to optimize force field parameters or control policies directly. This capability connects classical molecular simulation to modern gradient-based machine learning in a seamless computational graph.

These benchmarking principles extend beyond abstract test cases. Real molecular dynamics simulations, such as those studying adatom diffusion on metal surfaces, face similar challenges in understanding energy landscapes and transition pathways. The Müller-Brown potential provides a controlled environment for developing methods that eventually tackle these complex realistic systems.

Extension to Higher Dimensions

The canonical Müller-Brown potential can be extended beyond two dimensions to create more challenging test cases that better reflect real molecular systems. This extensibility demonstrates why it remains such an effective template for computational method development.

Why Higher Dimensions Matter

Real molecules have dozens or hundreds of degrees of freedom. Understanding how algorithms scale with dimensionality is crucial for practical applications. Higher-dimensional extensions allow researchers to systematically test:

- Algorithm scaling - Does performance degrade gracefully as dimensions increase?

- Model robustness - Do machine learning approaches maintain accuracy in high-dimensional spaces?

- Parallel efficiency - Can massively parallel methods exploit additional dimensions effectively?

Extension Approaches

Harmonic constraints: Add quadratic wells in orthogonal dimensions while preserving the complex 2D landscape[^sipka2023]:

$$V_{5D}(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4, x_5) = V(x_1, x_3) + \kappa(x_2^2 + x_4^2 + x_5^2)$$

The parameter $\kappa$ controls constraint strength: small values create nearly flat directions that test algorithmic efficiency.

Collective variables: Define new coordinates that mix multiple dimensions[^sun2022]:

$$\tilde{x} = \sqrt{x_1^2 + x_2^2 + \epsilon x_5^2},\quad \tilde{y} = \sqrt{x_3^2 + x_4^2}$$

where $\epsilon \ll 1$. The 5D potential becomes $V_{5D}(\tilde{x}, \tilde{y}) = V(\tilde{x}, \tilde{y})$, embedding the original surface in a higher-dimensional space.

Value for Algorithm Development

This extensibility makes the Müller-Brown potential ideal for systematic testing:

- Progressive complexity: Debug on 2D, then scale to higher dimensions

- Ground truth preservation: Known minima and saddle points remain in the active subspace

- Realistic challenges: Captures the “needle in a haystack” problem of transition state finding while maintaining analytical tractability

These extensions transform a simple 2D benchmark into a scalable testbed for modern computational methods, probing specific challenges in high-dimensional optimization.

Implementation in PyTorch

Now let’s implement the Müller-Brown potential in PyTorch. A practical implementation needs to handle batch processing, support both analytical and automatic differentiation, and be optimized for performance.

Core Implementation

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from torch import Tensor

class MuellerBrownPotential(nn.Module):

"""Müller-Brown potential with JIT-compiled force calculations."""

def __init__(

self,

device: str | torch.device = "cpu",

dtype: torch.dtype = torch.float64,

use_autograd: bool = False

):

super().__init__()

self.use_autograd = use_autograd

# Standard Müller-Brown parameters

self.register_buffer(

"A", torch.tensor([-200.0, -100.0, -170.0, 15.0],

device=device, dtype=dtype)

)

self.register_buffer(

"a", torch.tensor([-1.0, -1.0, -6.5, 0.7],

device=device, dtype=dtype)

)

self.register_buffer(

"b", torch.tensor([0.0, 0.0, 11.0, 0.6],

device=device, dtype=dtype)

)

self.register_buffer(

"c", torch.tensor([-10.0, -10.0, -6.5, 0.7],

device=device, dtype=dtype)

)

self.register_buffer(

"x_centers", torch.tensor([1.0, 0.0, -0.5, -1.0],

device=device, dtype=dtype)

)

self.register_buffer(

"y_centers", torch.tensor([0.0, 0.5, 1.5, 1.0],

device=device, dtype=dtype)

)

def forward(self, coordinates: Tensor) -> Tensor:

"""Compute potential energy."""

return _calculate_potential(

coordinates, self.A, self.a, self.b, self.c,

self.x_centers, self.y_centers

)

def force(self, coordinates: Tensor) -> Tensor:

"""Compute forces (negative gradient)."""

if self.use_autograd:

coordinates = coordinates.requires_grad_(True)

potential = self.forward(coordinates)

grad = torch.autograd.grad(potential.sum(), coordinates)[0]

return -grad

else:

return _calculate_force(

coordinates, self.A, self.a, self.b, self.c,

self.x_centers, self.y_centers

)

The implementation uses register_buffer to store parameters, a subtle but important PyTorch best practice. This ensures that the potential parameters are automatically moved to the GPU along with the model when calling .to(device), a common pitfall that leads to frustrating device mismatch errors. Beyond device placement, register_buffer also ensures these parameters are correctly handled during DistributedDataParallel (DDP) broadcasting, preventing silent failures when scaling training to multi-GPU clusters. The use_autograd flag switches between analytical and automatic differentiation.

JIT Compilation for Performance

PyTorch’s JIT compiler optimizes the mathematical operations for better performance:

@torch.jit.script

def _calculate_potential(coordinates: Tensor, A: Tensor, a: Tensor,

b: Tensor, c: Tensor, x_centers: Tensor,

y_centers: Tensor) -> Tensor:

"""JIT-scripted potential energy calculation."""

coords = coordinates.view(-1, 2)

x, y = coords[:, 0], coords[:, 1]

dx = x.unsqueeze(-1) - x_centers

dy = y.unsqueeze(-1) - y_centers

potential = torch.sum(

A * torch.exp(a * dx**2 + b * dx * dy + c * dy**2),

dim=-1

)

return potential.view(coordinates.shape[:-1])

@torch.jit.script

def _calculate_force(coordinates: Tensor, A: Tensor, a: Tensor,

b: Tensor, c: Tensor, x_centers: Tensor,

y_centers: Tensor) -> Tensor:

"""JIT-scripted force calculation."""

coords = coordinates.view(-1, 2)

x, y = coords[:, 0], coords[:, 1]

dx = x.unsqueeze(-1) - x_centers

dy = y.unsqueeze(-1) - y_centers

exp_terms = torch.exp(a * dx**2 + b * dx * dy + c * dy**2)

A_exp = A * exp_terms

grad_x = torch.sum(A_exp * (2 * a * dx + b * dy), dim=-1)

grad_y = torch.sum(A_exp * (b * dx + 2 * c * dy), dim=-1)

forces = torch.stack([-grad_x, -grad_y], dim=-1)

new_shape = list(coordinates.shape[:-1]) + [2]

return forces.view(new_shape)

By decorating the mathematical kernels with @torch.jit.script, we allow PyTorch to fuse operations and optimize the execution graph, effectively lowering interpreter overhead. More importantly, JIT enables kernel fusion: combining pointwise operations (like the exponential and polynomial terms) into a single CUDA kernel launch. This reduces memory bandwidth bottlenecks, which are often the true limiters in physics-ML workloads. The JIT compiler also eliminates Python’s dynamic dispatch, optimizes memory access patterns, and enables aggressive vectorization, critical for tight inner loops that execute millions of times per simulation.

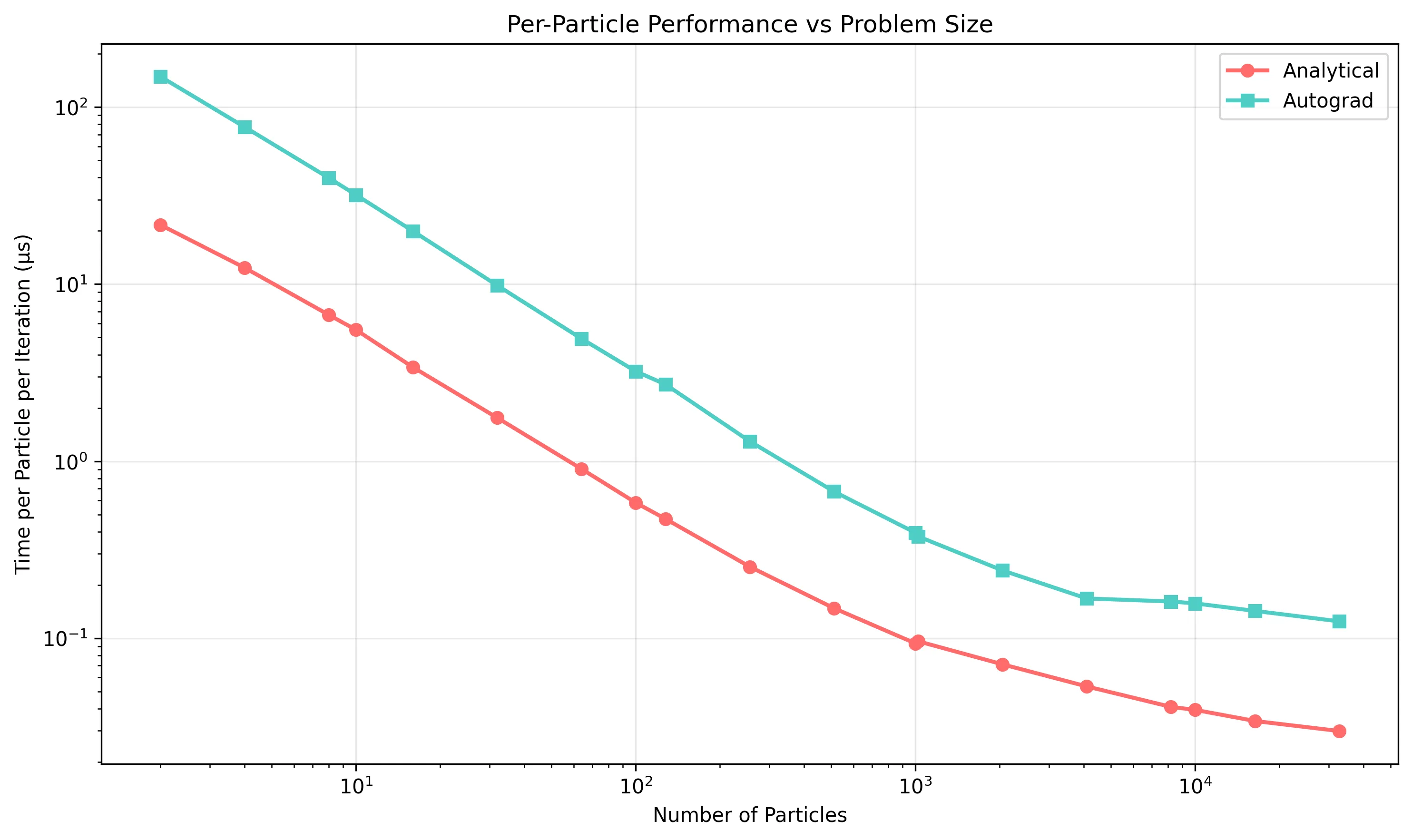

Performance: Analytical vs. Automatic Differentiation

A key design decision is whether to use analytical derivatives or automatic differentiation. I benchmarked both approaches on a 2020 MacBook Pro using PyTorch 2.0.1. To ensure statistical significance, these benchmarks utilized 100 warm-up iterations to stabilize system state, followed by 5 runs of 1000 iterations each. We report the median wall-clock time to filter out operating system jitter.

The 3-10x speedup represents a significant systems engineering victory. By deriving the analytical Jacobian, we bypass the computational graph construction required by PyTorch’s Autograd engine. Every autograd.grad() call must:

- Build a tape of operations during the forward pass

- Traverse the graph backward to compute gradients

- Allocate intermediate tensors for each node

For iterative workloads like molecular dynamics (millions of force evaluations per trajectory), this overhead elimination is critical. The analytical kernel computes forces directly in a single fused operation, no graph, no tape, no intermediate allocations.

When to use each approach:

- Analytical: Best for production molecular dynamics where forces are computed millions of times. The speedup directly reduces wall-clock simulation time.

- Autograd: Better for prototyping, machine learning training loops, or when implementing new potentials where correctness verification is paramount. The convenience and guaranteed accuracy often outweigh performance costs during development.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

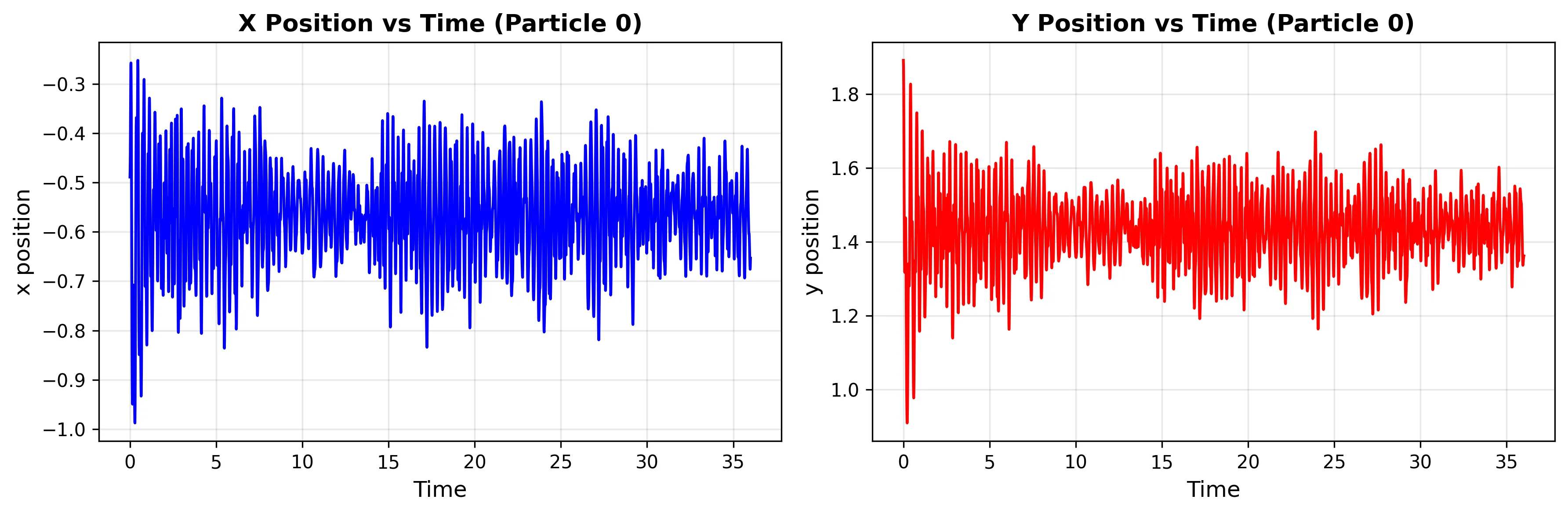

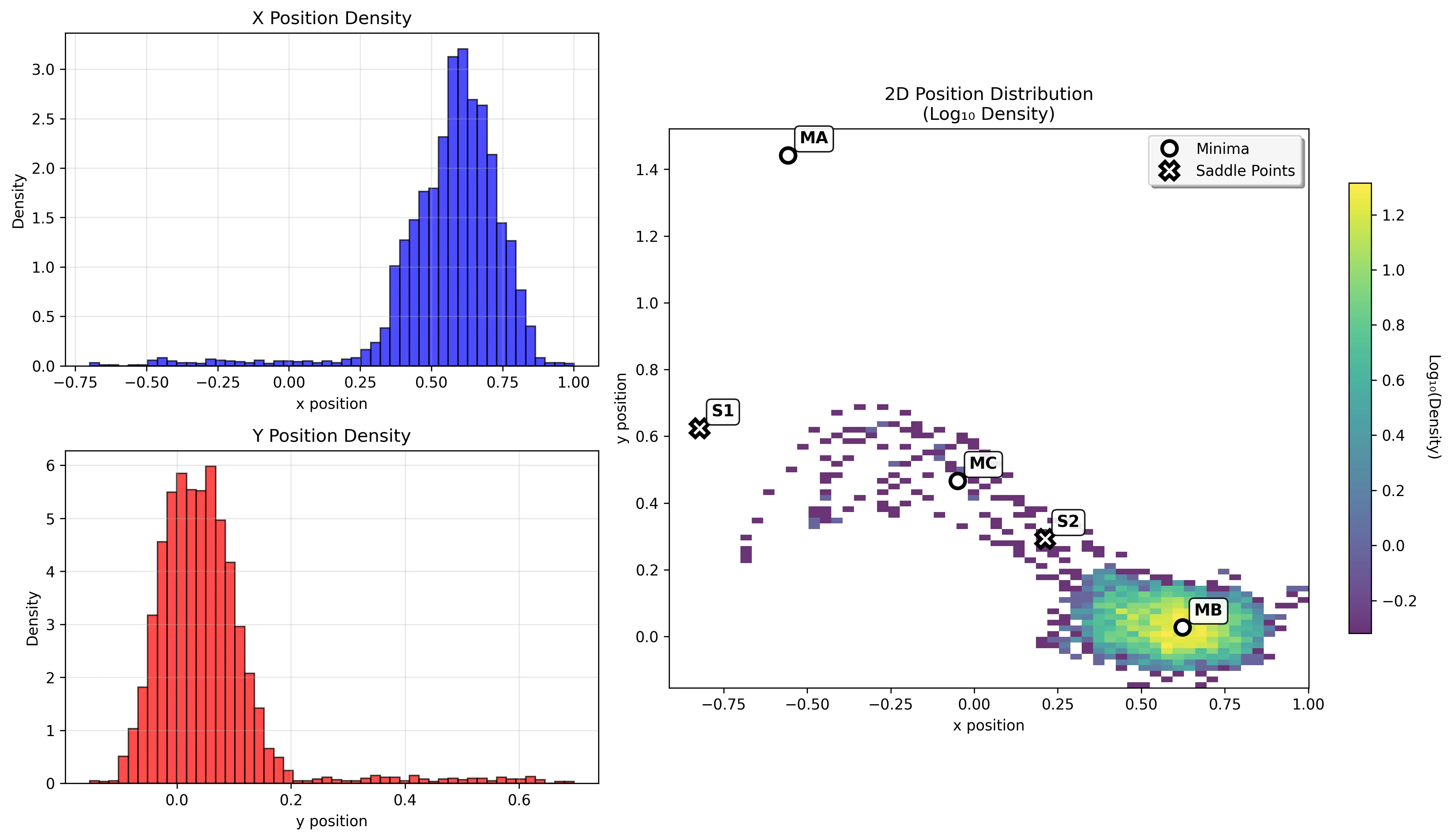

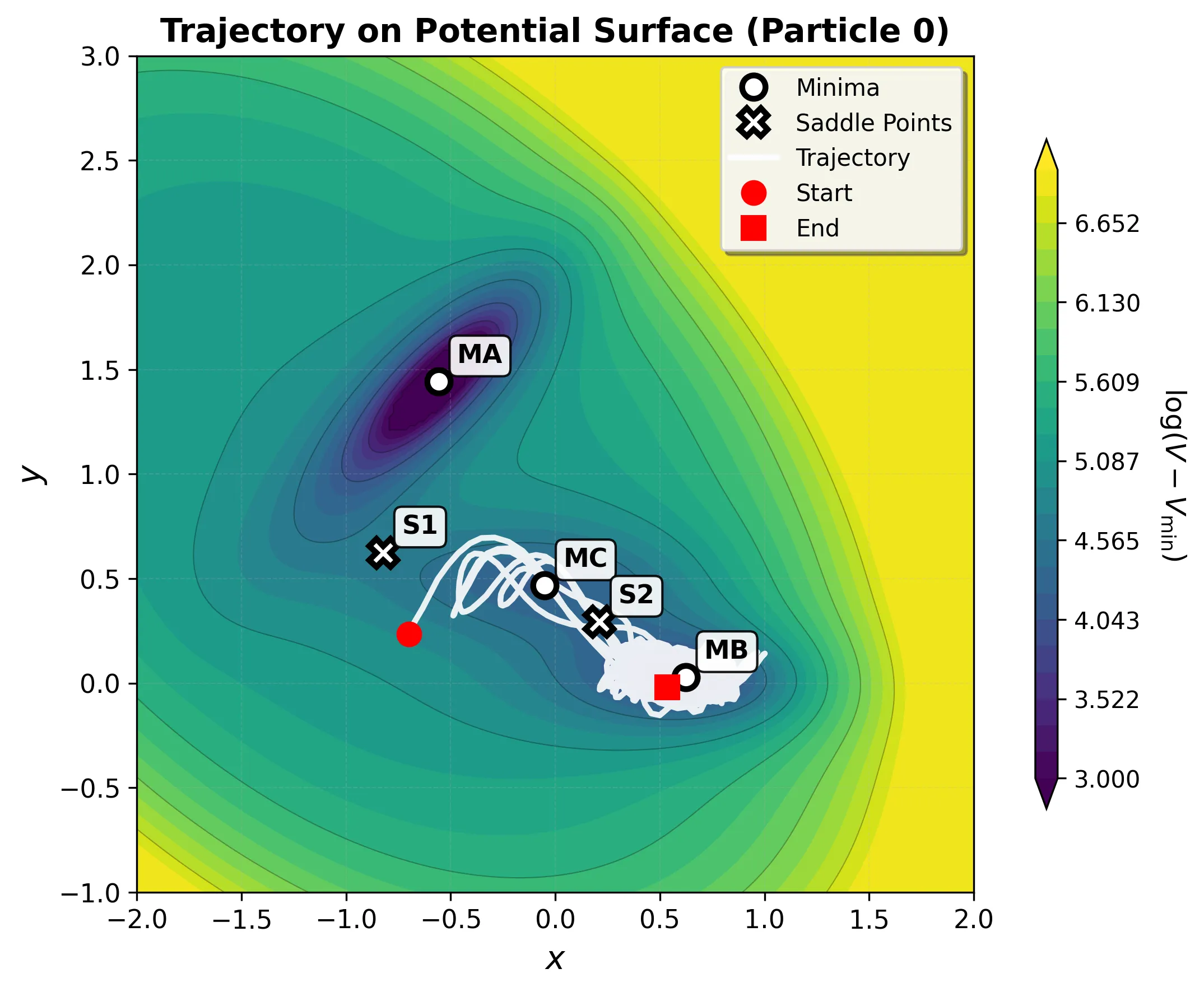

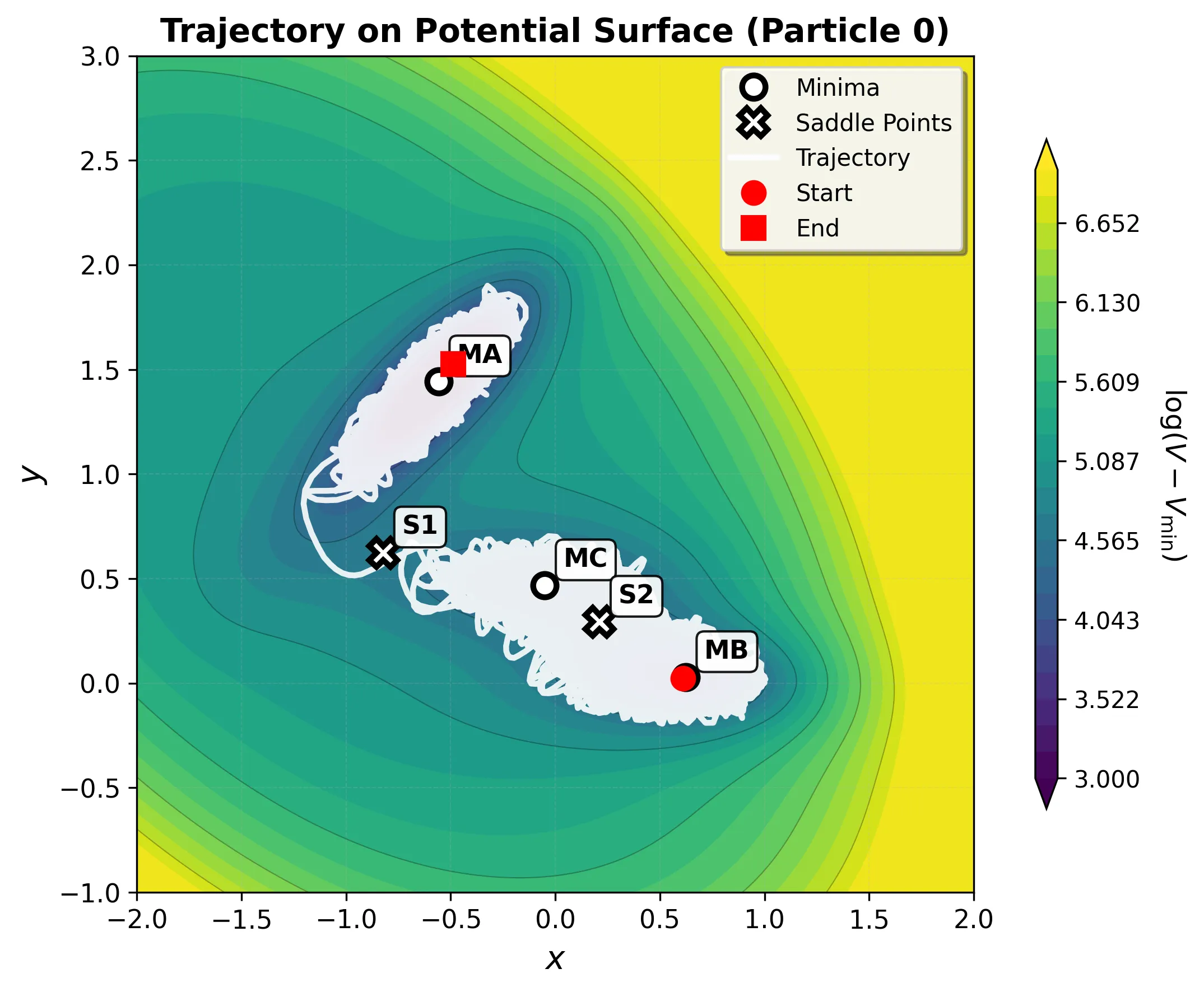

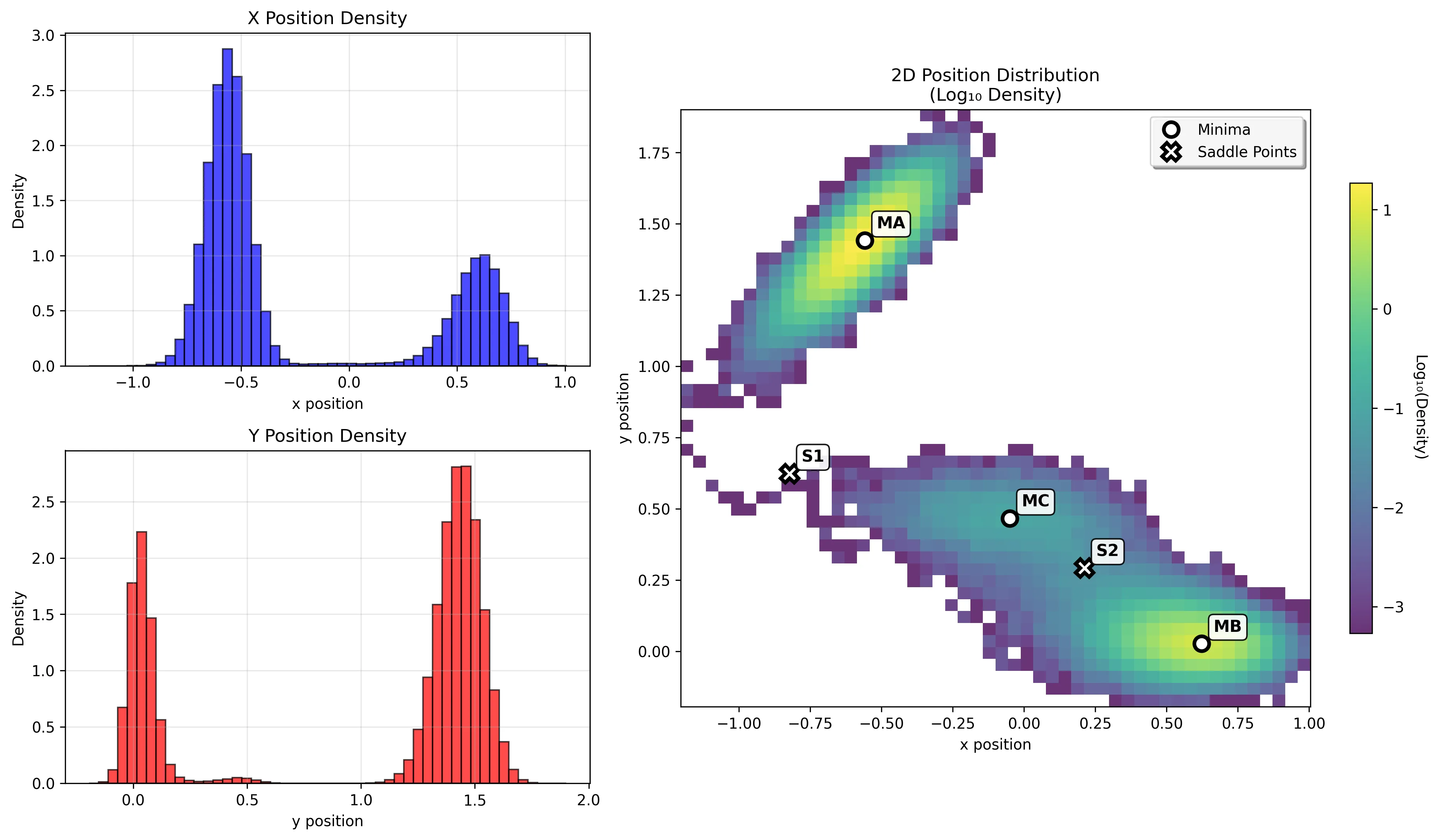

To demonstrate the PyTorch implementation in action, I performed Langevin dynamics simulations in different energy basins. These simulations reveal how particles behave when confined to different regions of the potential energy surface.

Simulation Parameters

I ran 3600 time steps with a 0.01 time unit step size, using a friction coefficient of 1.0 and temperature of 25.0 in reduced units. The simulations started from equilibrium positions within each basin and show the characteristic thermal fluctuations around local minima.

Basin MA: Deep Reactant Minimum

The deepest energy well (-146.70 kJ/mol) shows highly constrained motion due to the steep energy barriers surrounding it.

Basin MB: Product Minimum

The product minimum (-108.17 kJ/mol) shows intermediate behavior between the deep reactant well and shallow intermediate basin.

Transition Example

Running a longer simulation demonstrates transitions between basins:

Integration with Modern Workflows

The PyTorch implementation integrates naturally with machine learning workflows. It can serve as a component in larger computational graphs, enable gradient-based optimization, and bridge classical molecular simulation with deep learning approaches.

For readers interested in broader molecular ML applications, this implementation pairs well with other molecular representation methods. The Coulomb matrix approach offers complementary perspectives on encoding molecular structure, while the Kabsch algorithm provides essential tools for structural alignment.

The complete production-ready implementation is available on GitHub[^led_molecular][^vlachas2022][^vlachas2022b], including benchmarking scripts, visualization tools, and examples for optimization and molecular dynamics.

Conclusion

The Müller-Brown potential exemplifies how a well-designed benchmark can evolve with a field. Born from 1970s computational constraints, it provided a simple way to test algorithms when quantum chemistry calculations were expensive. Its clever design, simple enough to compute instantly, complex enough to break naive approaches, made it invaluable for algorithm development.

Today, it serves new purposes in the machine learning era. This PyTorch implementation demonstrates key engineering skills: deriving analytical Jacobians for performance-critical code, leveraging JIT compilation for near-C++ execution speed, and architecting modular components that integrate seamlessly with ML training pipelines. The 3-10x performance advantage of analytical derivatives remains important for intensive simulations, while PyTorch’s flexibility enables integration with neural network potentials and enhanced sampling methods.

The potential’s evolution from practical necessity to pedagogical tool to machine learning benchmark demonstrates the value of foundational test cases. As computational chemistry continues evolving, reliable standards like the Müller-Brown potential become even more important for rigorous method development and comparison.

For the complete production-ready implementation with benchmarking scripts, Langevin dynamics simulator, and visualization tools, see the GitHub repository.

[^muller1979]: Müller, K., & Brown, L. D. (1979). Location of saddle points and minimum energy paths by a constrained simplex optimization procedure. Theoretica Chimica Acta, 53, 75-93. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00547608 [^henkelman2000]: Henkelman, G., & Jónsson, H. (2000). Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. Journal of Chemical Physics, 113(22), 9901-9904. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1329672 [^dellago1998]: Dellago, C., Bolhuis, P. G., Csajka, F. S., & Chandler, D. (1998). Transition path sampling and the calculation of rate constants. Journal of Chemical Physics, 108(5), 1964-1977. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.475562 [^behler2007]: Behler, J., & Parrinello, M. (2007). Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Physical Review Letters, 98(14), 146401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.146401 [^smith2017]: Smith, J. S., Isayev, O., & Roitberg, A. E. (2017). ANI-1: an extensible neural network potential with DFT accuracy at force field computational cost. Chemical Science, 8(4), 3192-3203. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6SC05720A [^jones1931]: Lennard-Jones, J. E. (1931). Cohesion. Proceedings of the Physical Society, 43(5), 461-482. https://doi.org/10.1088/0959-5309/43/5/301 [^led_molecular]: LED-Molecular Repository - Original implementation of the Müller-Brown potential. https://github.com/cselab/LED-Molecular [^vlachas2022]: Vlachas, P. R., Zavadlav, J., Praprotnik, M., & Koumoutsakos, P. (2022). Accelerated simulations of molecular systems through learning of effective dynamics. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 18(1), 538-549. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00809 [^vlachas2022b]: Vlachas, P. R., Arampatzis, G., Uhler, C., & Koumoutsakos, P. (2022). Multiscale simulations of complex systems by learning their effective dynamics. Nature Machine Intelligence. https://www.nature.com/articles/s42256-022-00464-w [^sipka2023]: Sipka, M., Dietschreit, J. C. B., Grajciar, L., & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. (2023). Differentiable simulations for enhanced sampling of rare events. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 31990-32007). PMLR. [^sun2022]: Sun, L., Vandermause, J., Batzner, S., Xie, Y., Clark, D., Chen, W., & Kozinsky, B. (2022). Multitask machine learning of collective variables for enhanced sampling of rare events. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 18(4), 2341-2353.