In the world of automated document processing, Page Stream Segmentation (PSS)1 is the “hello world” problem that remains surprisingly stubborn.

The task is deceptively simple: given a stack of scanned pages (invoices, contracts, medical records), determine where one document ends and the next begins.

For decades, this problem was tackled with brittle rules and heuristics. Then came the deep learning era, where we threw Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and multipage Transformers at it. Yet, even sophisticated models struggled to achieve what businesses actually care about: Straight-Through Processing (STP).

Why STP Matters: Everyone interacting with the system cares about STP. Arguably, any human that has to interact with the output of a system, deal with its mistakes, and perform corrections to get a job done, cares about it. If the system fails 90% of the time, it fails to automate and creates more work at the expense of real people.

In this post, we explore the three eras of PSS, the limitations of page-level accuracy metrics, and how context-driven sequence modeling addresses these challenges.

The Hidden Complexity of PSS

Why is PSS hard? It comes down to ambiguity and asymmetry.

The “Document” Definition Problem

First, the concept of a “document” is highly context-dependent.

The “Word” Analogy: What is a word? A sequence of characters separated by spaces? Or a meaningful unit of language that can be a single character (e.g., “I”) or a compound (e.g., “New York”)? Is space a word, too? This ambiguity problem permeates all levels of language processing. We’d be naive to think PSS is an exception to this rule!

Consider an email with an attachment. Is the email body one document and the attachment another? Or is the whole packet one document? What about an invoice stapled to a check? A policy packet with multiple addendums?

“Solvability” implies a single ground truth, but in reality, PSS often requires aligning the model with specific, often subjective, business logic. A boundary to an underwriter might be a continuation to an archivist.

This subjectivity is a nightmare for rule-based systems. To solve it, we need models that go beyond pattern matching to reason about context and semantics. This is precisely where the self-attention mechanisms of Transformers excel.

The Cost of Error

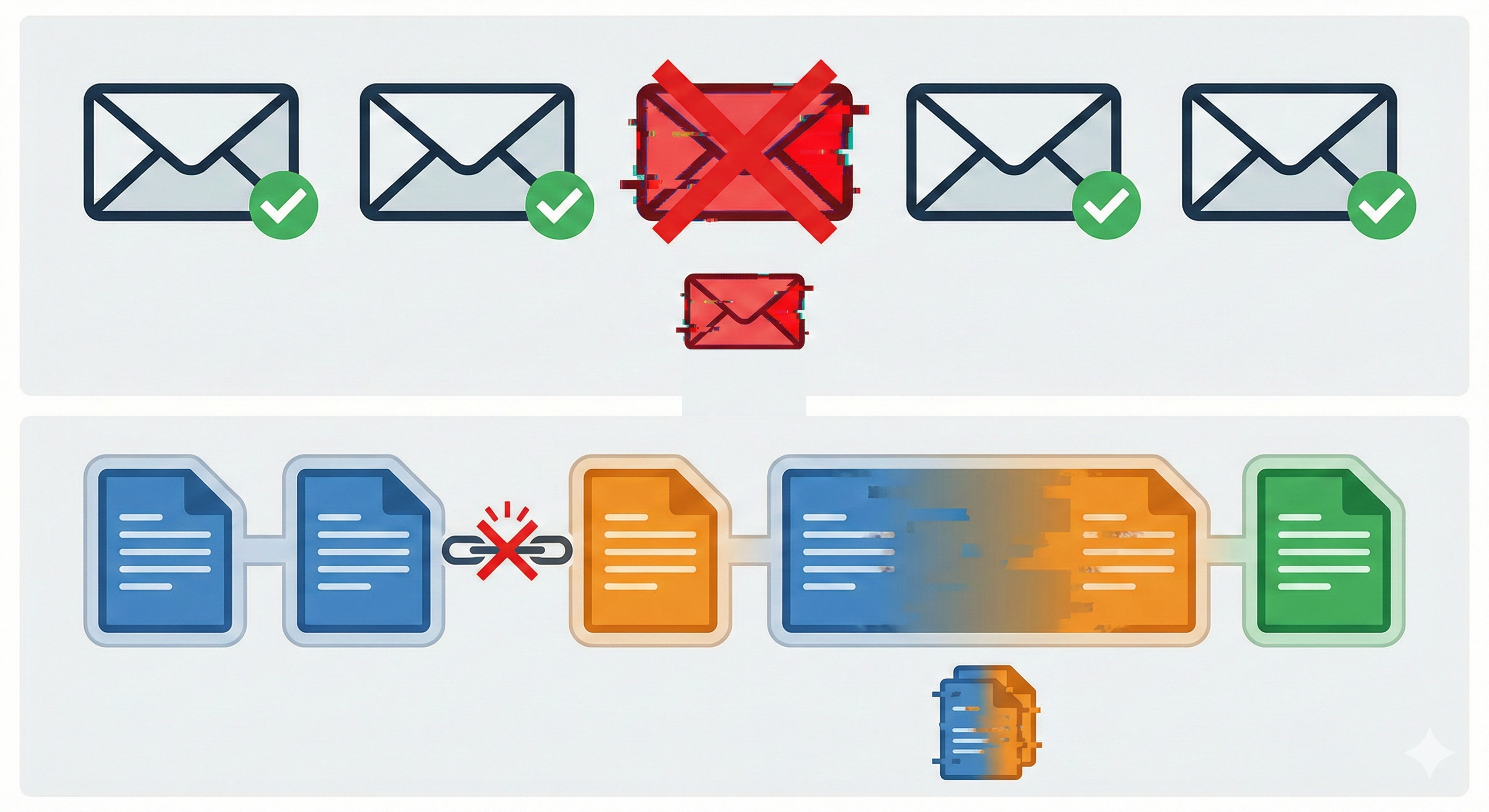

Second, the cost of failure is asymmetric.

If you are classifying an email as “Spam” or “Not Spam,” a single error affects one email. But PSS is a sequence problem. A single missed page break merges two distinct documents into one. This effectively “corrupts” two documents for the price of one error. Conversely, a false break splits a valid document in half.

Even more dismal, if our focus is truly STP, then the only acceptable outcome is perfect segmentation of an entire document stream. Sometimes faxes can be hundreds of pages long.

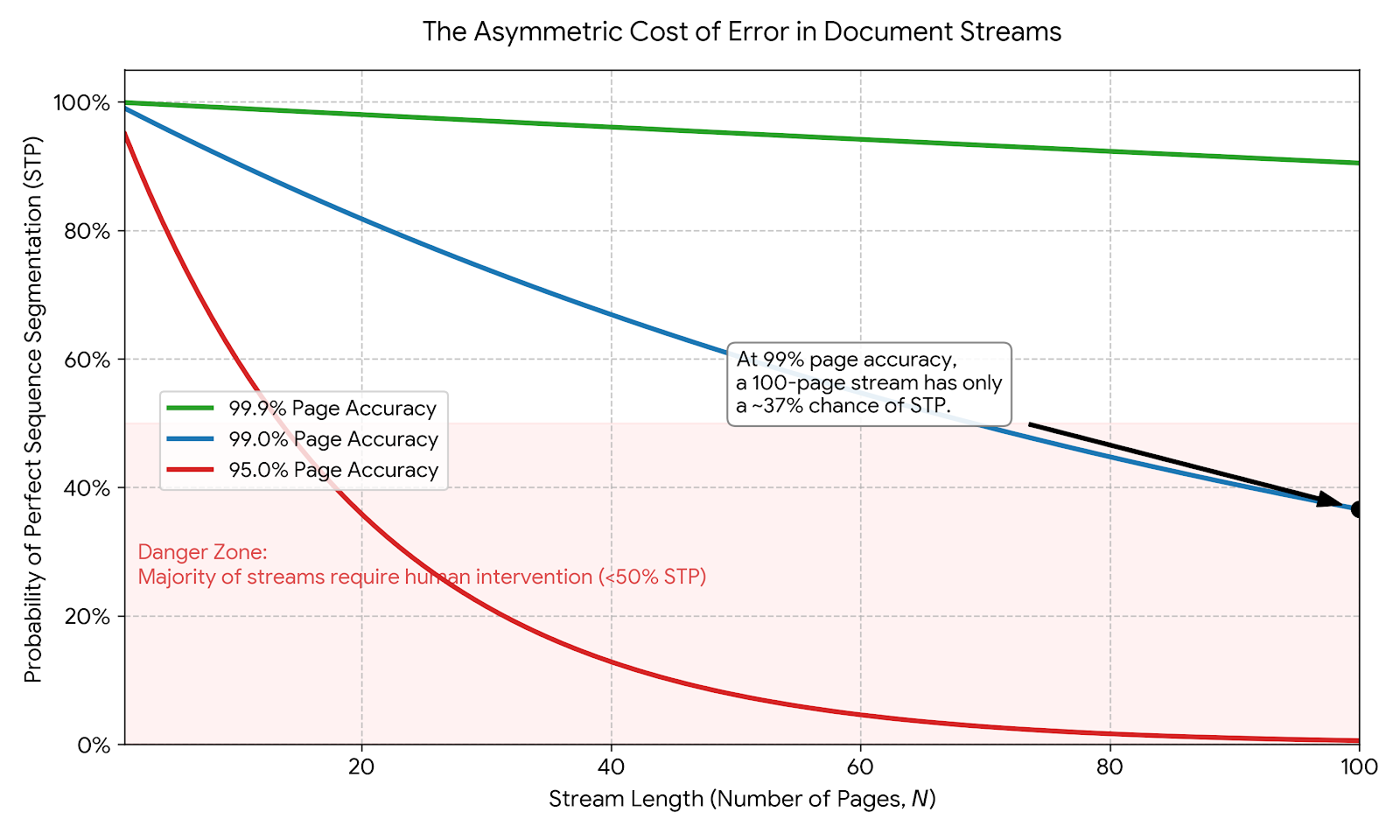

If we have a 99% page-level accuracy ($p=0.99$), the probability of correctly segmenting a 100-page stream ($N=100$) is only:

$$ P(\text{Success}) = p^N = 0.99^{100} \approx 0.37 $$

In other words, even with “high” accuracy, the vast majority of document streams will require human intervention. This phenomenon is what we call The Reliability Trap (explored in depth in our companion post).

The “F1 Score” Trap

A major finding in our research (TabMe++) is that traditional metrics mask the operational reality. Although generalized text segmentation metrics like $P_k$ and WindowDiff exist, we found they don’t capture the document-centric nature of business workflows.

Instead, we evaluate at three levels:

- Page-Level: Did we correctly classify this single page transition?

- Document-Level: Did we correctly identify the entire document tuple $d_k = (p_i, \ldots, p_j)$?

- Stream-Level: Did we perfectly segment the entire stack of documents?

Our results showed that Page-Level F1 Score completely masks the downstream impact.

Consider a baseline XGBoost model we tested:

- Page F1 Score: 0.83 (Sounds decent, right?)

- STP: 0.07 (Abysmal)

- MNDD: 10.85

That means 93% of document streams required human intervention. Even worse, the MNDD (Minimum Number of Drag-and-Drops)2 score tells us that for each stream, a human had to manually drag ~11 pages to fix the ordering.

This metric is crucial because it proxies the actual pain of the human in the loop. An error signifies more than a theoretical label flip; it forces a manual drag-and-drop operation.

Era 1: The Heuristic Era (2000s - 2015)

In the beginning, PSS was a game of if/else statements. Engineers hand-crafted heuristics tailored to specific document layouts, checking for signals like:

- Does the page contain “Page 1 of X”?

- Is there a “Total” line at the bottom?

- Does the header text change drastically?

While effective for known templates, these systems were inherently brittle. They relied on rigid assumptions about the input structure. If a vendor changed their invoice layout or OCR quality dipped, the logic would fail. They worked perfectly for what they were designed for but had zero capability to generalize to the unknown. Unfortunately, the real world is a constant state of exception.

Era 2: The Encoder Era (2015 - 2023)

As deep learning matured, researchers moved from hard-coded rules to learned representations.

- Visual Approaches: Using CNNs to look at the “shape” of a page as an image. First pages often look different from continuation pages (logos, big headers).

- Word Vectors: Early NLP attempts used tools like doc2vec to represent page content, but these “averaged” the text, losing sequential meaning.

- Multimodal Transformers: Eventually, models like LayoutLM and LEGAL-BERT tried to combine text and layout into a single understanding.

While these models were “smarter” than rules, they suffered from distinct limitations:

Field Lag: Surprisingly, only a handful of studies applied Transformers to PSS before 2024. Most of the industry was still stuck on older CNN architectures.

Context Windows: Encoder models like BERT are limited to 512 tokens. A dense legal contract page might have 1,000+ tokens. You had to chop the text, losing critical context.

Modality Overload: Counterintuitively, our experiments showed that naively adding modalities (Text + Layout + Vision) often yielded diminishing returns. Models like LayoutLMv3 struggled to outperform simpler vision-only or text-only models on our benchmark.

However, looking continuously at the data reveals an interesting nuance: Visual signals matter. In our tests, the vision-only model (DiT) actually outperformed the text-only model (RoBERTa). They often have better recall whereas text-only models can better optimize for precision. The multimodal models failed due to the difficulty of aligning modalities. Vision remains a highly useful signal. This insight led us to a key realization for Era 3: What if we could give the model visual information without the architectural headache of a vision encoder?

Era 3: The Decoder Era (2024 - Present)

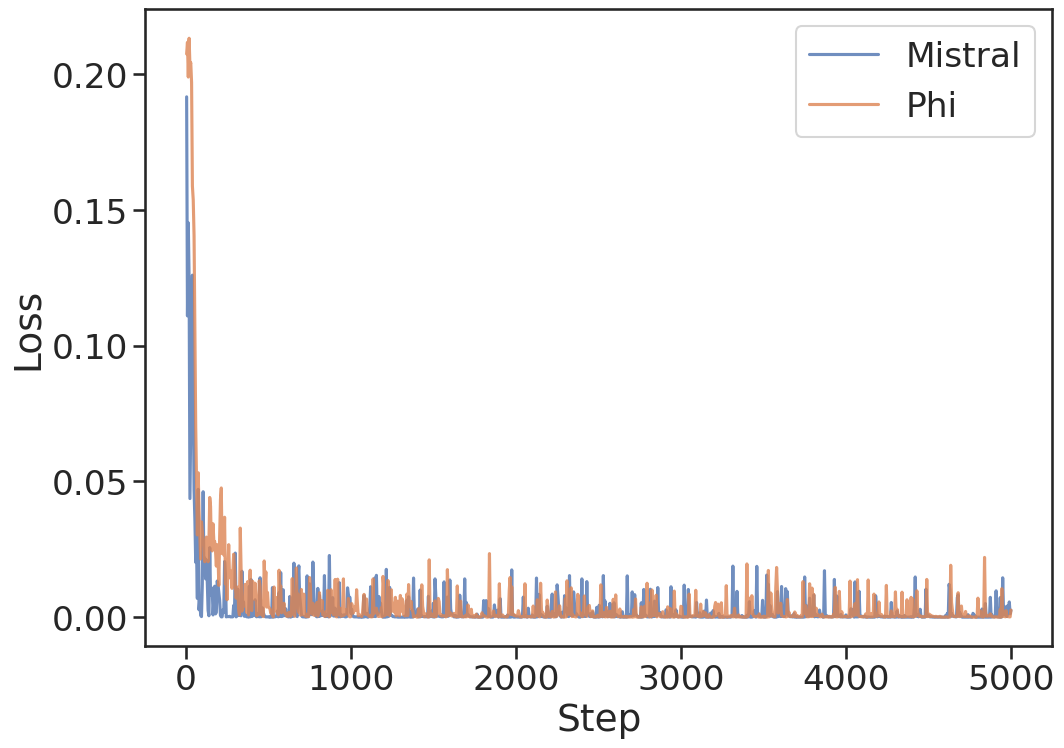

The breakthrough came with applying Decoder-only Large Language Models (LLMs) like Mistral-7B and Phi-3 to the task.

Why do LLMs succeed where specialized encoders failed? Contextual Processing.

Determining if a page is a continuation often requires analyzing sequential dependencies.

- Does the sentence cut off mid-thought?

- Does the next page logically follow the argument of the previous one?

- Is the “Policy Number” on Page 2 the same as Page 1?

LLMs are pre-trained on the internet; they model narrative flow and document structure effectively. By fine-tuning them on pairs of pages, we adapted these priors to recognize specific segmentation boundaries.

2D Projection & Data Quality

We employed 2D Text Projection, a technique that serializes OCR output by mapping spatial coordinates to whitespace. This effectively “draws” the layout using text characters, allowing the LLM to process columns, headers, and form structures. We translated the visual signal (layout) into the text modality to address the “Modality Overload” problem.

To be clear, this is a lossy compression. We discard font sizes, bolding, colors, and line separators. It is merely a cheap, zeroth-order approximation of 2D layout using 1D text. Yet, as our results show, this approximation captures the semantic essence of the layout (e.g., “this text is in a header column”) sufficient for the model to reason about document boundaries.

However, this technique has a hard dependency: Data Quality. 2D projection is useless if your OCR gives you garbage coordinates. This is where our work on TabMe++ (discussed below) became critical. You can’t project a layout if the OCR misses the text or places it in the wrong spot.

# Original Raw Text (Loss of Layout)

INVOICE # 1024 DATE: 2024-02-14 TOTAL: $500.00

# 2D Projected Text (Layout Preserved)

INVOICE # 1024

DATE: 2024-02-14

TOTAL: $500.00

Why Does This Work? Modern LLMs are trained on a mixture of web text, code, and even some structured data. They have learned to interpret whitespace and formatting cues as part of their understanding of language. By encoding layout information into the text itself, we leverage the LLM’s existing capabilities without needing to train a separate vision encoder.

We then wrapped this input in a structured prompt that explicitly framed the task for the LLM:

You are a skilled document reviewer. Given extracted text from pages of documents, your task is to determine if a page starts a new document or continues from the previous one.

...

Prior text:

###

{pg_prev}

###

Page text:

###

{pg}

###

Output your prediction as a JSON object...

The Results

We formulated the task as a binary classification problem on page pairs. We fed the model (Page N, Page N+1) and asked: “Does Page N+1 start a new document?”

Comparison on TabMe++ Benchmark:

| Model Type | Model Name | Page F1 | STP (Higher is better) | MNDD (Lower is better) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | XGBoost | 0.83 | 7.4% | 10.85 |

| Encoder | RoBERTa (Text) | 0.78 | 4.2% | 12.17 |

| Encoder | DiT (Vision) | 0.83 | 6.6% | 10.48 |

| Decoder | Mistral-7B (Fine-Tuned) | 0.99 | 80.0% | 0.81 |

The difference is stark. Moving from Encoders to Decoders increased the automation rate from ~7% to 80% and reduced the human effort (MNDD) by a factor of 10. Note: This 80% represents the model’s raw accuracy. As we discuss in The Reliability Trap, achieving “production-safe” automation often requires setting strict confidence thresholds, which effectively lowers the safe throughput.

Why Fine-Tuning Matters: The GPT-4o Comparison

You might look at the chart above and ask: “Is the model learning PSS, or does it just rely on pre-trained language statistics?”

To test this, we ran GPT-4o in a zero-shot setting on the same task. The result was an STP of roughly 9%.

Zero-shot GPT-4o performed similarly to our XGBoost baseline. This demonstrates that broad pre-training requires specific instruction tuning to capture business logic. Our 7B model achieved 80% STP after fewer than 1,000 updates.

This proves two things:

- Broad Pre-training Requires Tuning. Modeling generic document distributions must be adapted to capture specific business logic for segmentation.

- The Capabilities are Latent. The rapid convergence implies the model possesses the necessary statistical priors and requires fine-tuning to align those priors with the specific task. We are adjusting the decision boundary between a generic “document” and a specific business record.

The Cost of Intelligence and the Value of Human Time

Critically, we must address the two elephants in the room: Inference Cost and Data Privacy.

It is true that running a 7B parameter LLM for every page pair is computationally more expensive than a lightweight XGBoost model. However, focusing solely on compute costs misses the operational and human reality of this work.

Economically, the “cheap” model is a mirage. When a low-accuracy model forces a human to reorganize 93% of document streams, the cost of rectification, specifically wasted salaries and slowed turnaround times, dwarfs the cost of GPU inference. But the financial argument is secondary to the human one.

Manually segmenting documents is, frankly, soul-sucking. It is tedious, repetitive drudgery that few people enjoy. Beyond operational expense, we are discussing human burnout. A model that achieves 80% full automation (STP) saves money while liberating people from the mind-numbing task of sorting pages. This allows them to focus on work that actually requires their creativity and empathy. We are trading cheap FLOPs for valuable human attention.

Furthermore, democratizing this capability has profound implications beyond the enterprise. If we can make high-quality segmentation usable on modest hardware (like a high-end laptop or a single commodity GPU), we open the door for archivists, librarians, digital humanists, and small cities or towns that have little to no resources for this kind of work. These are the custodians of our collective intelligence, often working with massive, unorganized scanned collections but lacking the budget for massive cloud clusters.

Our results showed that 7B parameter models (like Mistral) are sufficient to solve this task. This size is the sweet spot: powerful enough to reason, but small enough to run locally. This matters for data sovereignty (keeping medical records private) and accessibility. It means a small historical society could potentially automate the organization of a century’s worth of digitized records without a massive grant for cloud compute.

That said, a 7B model might not be the lower bound. While it was the breakthrough size for our study, the recent explosion of capable 1B-3B models suggests we haven’t hit the efficiency floor yet. Combined with extreme quantization, modern small language models (SLMs) likely offer the “Goldilocks” zone: enough reasoning to maintain high STP, but fast enough to run continuously on modest hardware. We suspect the future of PSS lies in these highly optimized, smaller reasoning models that can run anywhere… from a bank’s secure server to a researcher’s laptop.

The Importance of Data Quality

Data quality presented an equal challenge to algorithmic limitations. Most public datasets (like Tobacco800) were small or unrealistic. The TABME dataset (precursor to our work) relied on open-source Tesseract OCR, which missed vast amounts of text.

We released TabMe++, which re-processed the entire dataset with commercial-grade Microsoft OCR.

- Blank Pages: Reduced from 2.27% $\rightarrow$ 0.38%.

- Token Count: Increased from 719M $\rightarrow$ 9.5B.

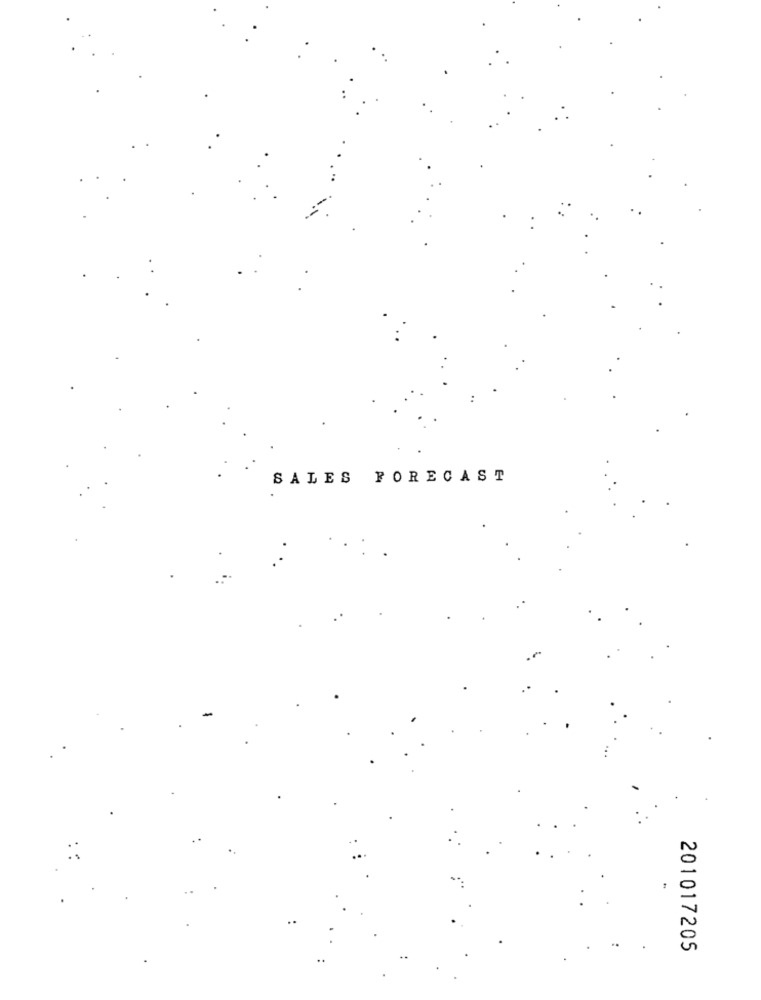

The difference in intelligibility is night and day. Consider the page above.

Tesseract (Original):

02Z10102

(Misses almost everything, including the title and real ID)

Microsoft OCR (TabMe++):

SALES FORECAST

201017205

(Correctly captures the spatial layout, the title, and the ID)

Lesson: You can’t segment what you can’t read. High-quality OCR (or multimodal front-ends) is the foundation of high-quality downstream NLP.

The Next Frontier: Context and Instruction Following (2026+)

As we discussed earlier, the definition of a “document” is subjective. To one team, an email + attachment is a single record. To another, they are distinct entities. A rigid model that segments perfectly for Team A will fail miserably for Team B.

The zero-shot GPT-4o results demonstrate that scale requires adaptation. The future of PSS depends on instruction tuning. We need models that can accept natural language rules alongside the document stream:

“Split all invoices, but keep attachments with their parent emails. If you see an ACORD form, group it with the subsequent policy document.”

This shift mirrors the broader evolution of LLMs. PSS models must evolve into dynamic systems capable of instruction following. A single model should be able to adapt to any business logic without retraining.

Furthermore, while our 2024 research favored unimodal text models with 2D projection, the multimodal landscape is shifting. With the rise of natively multimodal models (like Gemini, GPT-4o, and our own GutenOCR), we effectively get the “2D projection” natively. Future models will seamlessly fuse this native visual understanding with deep semantic reasoning, all guided by user-defined constraints.

Conclusion

Page Stream Segmentation is a perfect case study in the evolution of AI. We moved from encoding rules (Heuristic Era) to encoding features (Encoder Era) to encoding understanding (Decoder Era).

For enterprise professionals, the takeaways are clearer and more critical than ever.

First, stop looking at element-wise F1 scores for sequence tasks. While element-wise metrics are useful for engineers debugging algorithms, they are misleading for decision-makers. Focus on the metrics that actually affect people and workflows, like Straight-Through Processing (STP) and Minimum Number of Drag-and-Drops (MNDD).

Second, if you want to solve PSS today, start with an inward-looking conversation about “for what.” Before picking a model, answer these questions:

- Inputs: What assumptions are you making about your document stream?

- Outcomes: What specific business outcomes are you hoping to see?

- Context: What is the core motivation for this workflow?

- Nuance: Are there informative scenarios (like the “email attachment” problem) that illustrate your specific needs?

Given these answers, many modern approaches can unlock PSS for you. Whether you need an on-premise solution for secure scenarios using lightweight open-weights models, or can leverage powerful AI-as-a-Service APIs, the technology is no longer the bottleneck; understanding your own requirements is.

For full technical details, experimental setups, and datasets, refer to our paper: Large Language Models for Page Stream Segmentation or view the preprint on arXiv:2408.11981. Much of the initial work was also documented in a precursor blog series at Roots Automation (Part 1 & Part 2).

Historically, this task has gone by many names: document separation, document flow segmentation, document stream segmentation, document bundle separation, and page stream separation. We stick to Page Stream Segmentation (PSS) to emphasize the sequential nature of the problem. ↩︎

We adopted the MNDD metric from Mungmeeprued et al. (2022), who introduced it alongside the original TABME dataset to better quantify the human effort required to correct segmentation errors. ↩︎