What kind of paper is this?

This is a foundational Theory paper. It establishes the mathematical framework for modern information theory and defines the ultimate physical limits of communication for an entire system, from the information source to the final destination.

What is the motivation?

The central motivation was to develop a general theory of communication that could quantify information and determine the maximum rate at which it can be transmitted reliably over a noisy channel. Prior to this work, communication system design was largely empirical. Shannon sought to create a mathematical foundation to understand the trade-offs between key parameters like bandwidth, power, and noise, independent of any specific hardware or modulation scheme. To frame this, he conceptualized a general communication system as consisting of five essential elements: an information source, a transmitter, a channel, a receiver, and a destination.

What is the novelty here?

The novelty is a complete, end-to-end mathematical theory of communication built upon several groundbreaking concepts and theorems:

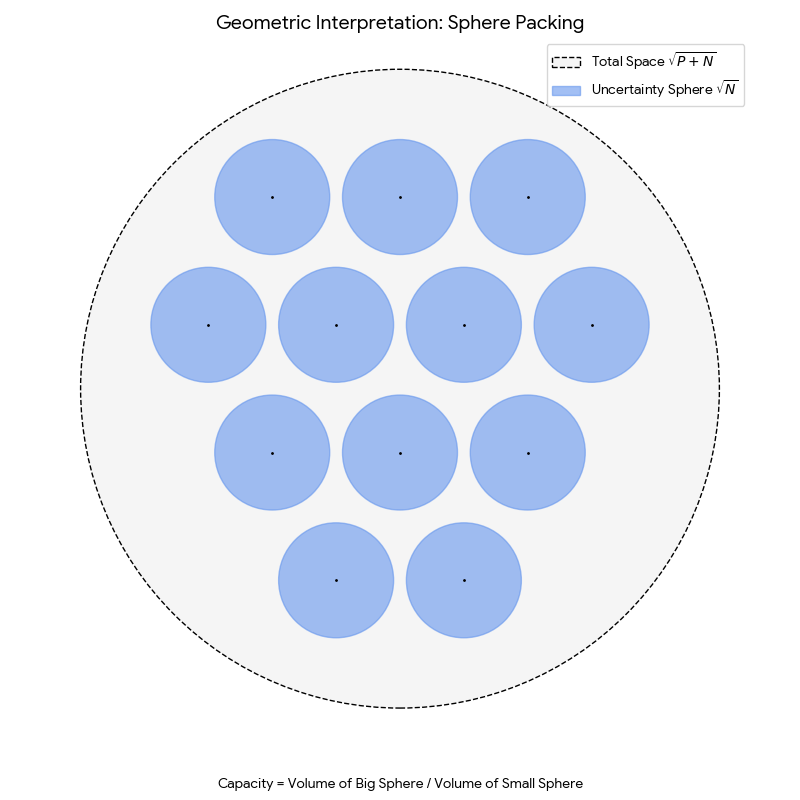

- Geometric Representation of Signals: Shannon introduced the idea of representing signals as points in a high-dimensional vector space. A signal of duration $T$ and bandwidth $W$ is uniquely specified by $2TW$ numbers (its samples), which are treated as coordinates in a $2TW$-dimensional space. This transformed problems in communication into problems of high-dimensional geometry. In this representation, signal energy corresponds to squared distance from the origin, and noise introduces a “sphere of uncertainty” around each transmitted point.

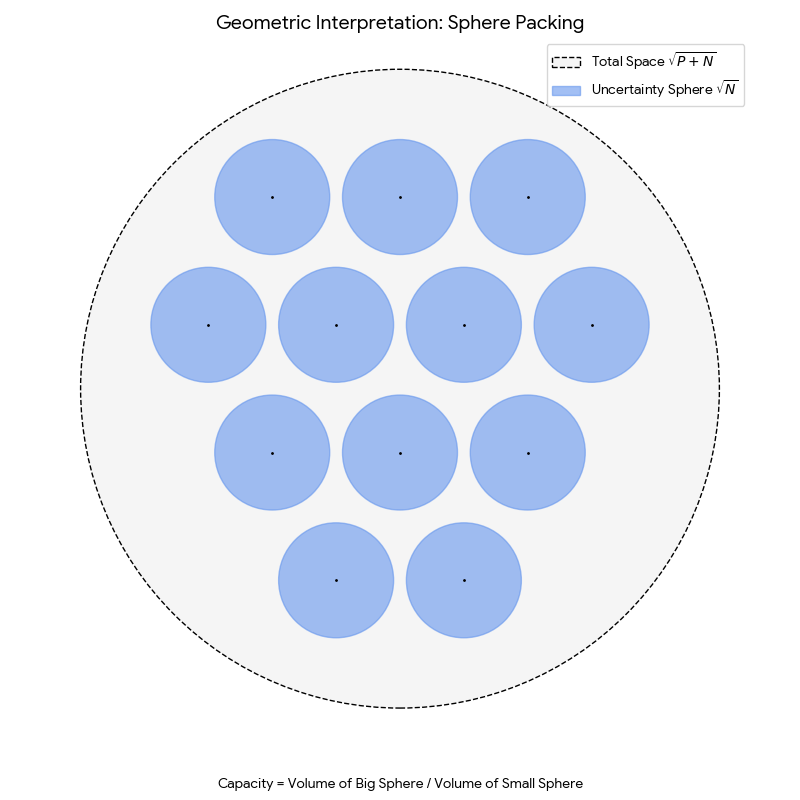

Theorem 1 (The Sampling Theorem): The paper provides an explicit statement and proof that a signal containing no frequencies higher than $W$ is perfectly determined by its samples taken at a rate of $2W$ samples per second (i.e., spaced $1/2W$ seconds apart). Shannon explicitly credits Harry Nyquist for pointing out the fundamental importance of this time interval, formally naming it the “Nyquist interval” corresponding to the band $W$. This theorem is the theoretical bedrock of all modern digital signal processing.

Theorem 2 (Channel Capacity for AWGN): This is the paper’s most celebrated result, the Shannon-Hartley theorem. It provides an exact formula for the capacity $C$ (the maximum rate of error-free communication) of a channel with bandwidth $W$, signal power $P$, and additive white Gaussian noise of power $N$: $$ C = W \log_2 \left(1 + \frac{P}{N}\right) $$ It proves that for any transmission rate below $C$, a coding scheme exists that can achieve an arbitrarily low error frequency.

Random Coding Proof Technique: Shannon’s proof employs a random coding argument: he proved that if you choose signal points at random from the sphere of radius $\sqrt{2TWP}$, the average error frequency vanishes for any transmission rate below capacity. This non-constructive proof (meaning it establishes that good codes must exist without constructing any specific one) established that “good” codes exist almost everywhere in the signal space, even if we don’t know how to build them efficiently. The random coding argument became a fundamental tool in information theory, shifting the focus from building specific codes to proving existence and understanding fundamental limits.

Theorem 3 (Channel Capacity for Arbitrary Noise): Shannon generalized the capacity concept to channels with any type of noise. Entropy power is defined as $N_1 = \frac{1}{2\pi e} e^{2h(X)}$, where $h(X)$ is the differential entropy of the noise distribution (the continuous analog of discrete entropy $H$: where $H$ counts the average bits per symbol from a discrete source, $h(X)$ measures the same unpredictability for continuous-valued random variables); it quantifies how spread out a distribution is in an information-theoretic sense, with Gaussian noise having the highest entropy power for a given variance. He showed that the capacity for a channel with arbitrary noise of power $N$ is bounded by the noise’s entropy power $N_1$. Shannon proved that white Gaussian noise is the worst possible type of noise for any given noise power. By the entropy power inequality, the entropy power $N_1$ of any noise with variance $N$ satisfies $N_1 \leq N$, with equality only for the Gaussian distribution. Since channel capacity decreases as entropy power increases, Gaussian noise achieves the highest $N_1$ (equal to $N$) and therefore imposes the lowest capacity bound. This means a system designed to handle white Gaussian noise will perform at least as well against any other noise type of the same power.

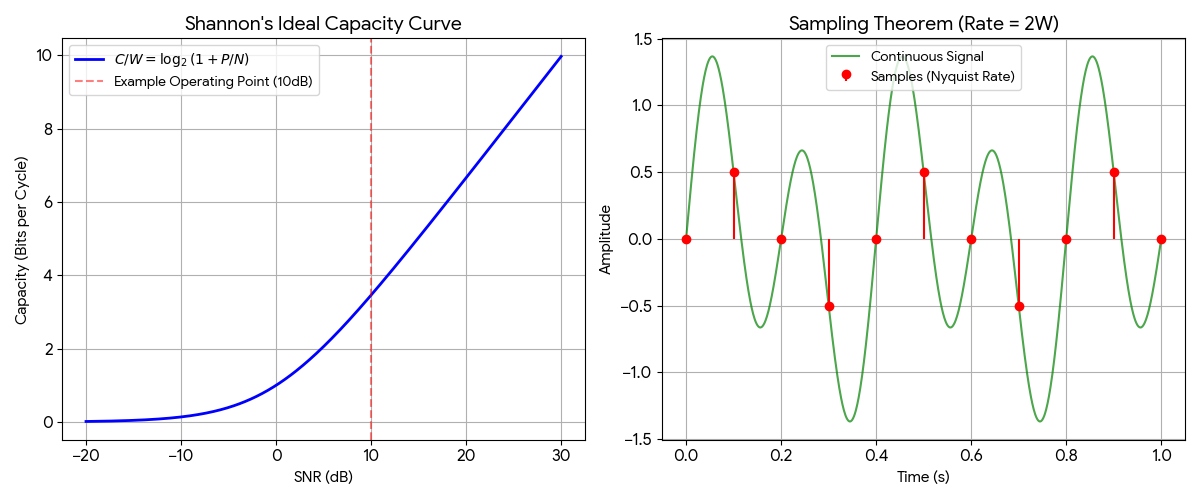

Arbitrary Gaussian Noise and the Water-Filling Principle: Shannon extended his analysis to Gaussian noise with a non-flat power spectrum $N(f)$, using the calculus of variations (a technique for optimizing over functions rather than fixed variables) to find the power allocation $P(f)$ that maximizes capacity. He proved that optimal capacity is achieved when the sum $P(f) + N(f)$ is constant across the utilized frequency band. This leads to what is now known as the “water-filling” principle: allocate more signal power to quieter frequency bands, and allocate zero power to any band where noise exceeds the constant threshold. This provides the foundation for modern adaptive power allocation across frequency bands.

Theorem 4 (Source Coding Theorem): This theorem addresses the information source itself. It proves that it’s possible to encode messages from a discrete source into binary digits such that the average number of bits per source symbol approaches the source’s entropy, $H$. This establishes entropy as the fundamental limit of data compression.

Theorem 5 (Information Rate for Continuous Sources): For continuous (analog) signals, Shannon introduced a concept foundational to rate-distortion theory. He defined the rate $R$ at which a continuous source generates information relative to a specific fidelity criterion (i.e., a tolerable amount of error, $N_1$, in the reproduction). This provides the basis for all modern lossy compression algorithms.

What experiments were performed?

The paper is primarily theoretical, with “experiments” consisting of rigorous mathematical derivations and proofs. The channel capacity theorem, for instance, is proven using a geometric sphere-packing argument in the high-dimensional signal space.

However, Shannon does include a quantitative theoretical benchmark against existing 1949 technology. He plots his theoretical “Ideal Curve” against calculated limits of Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) and Pulse Position Modulation (PPM) systems in Figure 6. The PCM points were calculated from formulas in another paper, and the PPM points were from unpublished calculations by B. McMillan. This comparison reveals that the entire series of plotted points for these contemporary systems operated approximately 8 dB below the ideal power limit over most of the practical range. Interestingly, PPM systems approached to within 3 dB of the ideal curve specifically at very small $P/N$ ratios, highlighting that different modulation schemes are optimal for different regimes (PCM for high SNR, PPM for power-limited scenarios).

What outcomes/conclusions?

The primary outcome was a complete, unified theory that quantifies both information itself (entropy) and the ability of a channel to transmit it (capacity).

Decoupling of Source and Channel: A key conclusion is that the problem of communication can be split into two distinct parts: encoding sequences of message symbols into sequences of binary digits (where the average digits per symbol approaches the entropy $H$), and then mapping these binary digits into a particular signal function of long duration to combat noise. A source can be transmitted reliably if and only if its rate $R$ (or entropy $H$) is less than the channel capacity $C$.

The Limit is on Rate: Shannon’s most profound conclusion was that noise in a channel imposes a maximum rate of transmission. Below this rate, error-free communication is theoretically possible.

The Threshold Effect and Topological Necessity: To approach capacity, one must map a lower-dimensional message space into the high-dimensional signal space efficiently, like winding a “ball of yarn” to fill the available signal sphere. This complex mapping creates a sharp threshold effect: below a certain noise level, recovery is essentially perfect; above it, the system fails catastrophically because the “uncertainty spheres” around signal points begin to overlap. Shannon provides a profound topological explanation for why this threshold is unavoidable: it is impossible to continuously map a higher-dimensional space into a lower-dimensional one. To compress bandwidth (reducing the number of dimensions in signal space), the mapping from message space to signal space must necessarily be discontinuous. This required discontinuity creates vulnerable points where a small noise perturbation can cause the received signal to “jump” to an entirely different interpretation. The threshold is an inevitable consequence of dimensional reduction. This explains the “cliff” behavior seen in digital communication systems, where performance is excellent until it suddenly fails.

The Exchange Relation: Shannon explicitly states that the key parameters $T$ (time), $W$ (bandwidth), $P$ (power), and $N$ (noise) can be “altered at will” as long as the channel capacity $C$ remains constant. This exchangeability is a fundamental insight for system architects, enabling trade-offs such as using more bandwidth to compensate for lower power.

Characteristics of an Ideal System: The theory implies that to approach the channel capacity limit, one must use very complex and long codes. An ideal system exhibits five key properties: (1) the transmission rate approaches $C$, (2) the error probability approaches zero, (3) the transmitted signal’s statistical properties approach those of white noise, (4) the threshold effect becomes very sharp (errors increase rapidly if noise exceeds the designed value), and (5) the required delay increases indefinitely. This final constraint is a crucial practical limitation: achieving near-capacity performance requires encoding over increasingly long message blocks, introducing latency that may be unacceptable for real-time applications.

Reproducibility Details

Algorithms

The paper introduces the theoretical foundation for the water-filling algorithm for optimal power allocation across frequency bands with varying noise levels. The mathematical condition derived is that $P(f) + N(f)$ must be constant across the utilized frequency band.

Paper Information

Citation: Shannon, C. E. (1949). Communication in the Presence of Noise. Proceedings of the IRE, 37(1), 10-21. https://doi.org/10.1109/JRPROC.1949.232969

Publication: Proceedings of the IRE, 1949

@article{shannon1949communication,

author={Shannon, C. E.},

journal={Proceedings of the IRE},

title={Communication in the Presence of Noise},

year={1949},

volume={37},

number={1},

pages={10-21},

doi={10.1109/JRPROC.1949.232969}

}