Paper Information

Citation: Morin, L., Meijer, G. I., Weber, V., Van Gool, L., & Staar, P. W. J. (2025). Subgrapher: Visual fingerprinting of chemical structures. Journal of Cheminformatics, 17(1), 149. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-025-01091-4

Publication: Journal of Cheminformatics (2025)

Paper Classification and Taxonomy

This is primarily a Methodological Paper ($\Psi_{\text{Method}}$) with a secondary Resource ($\Psi_{\text{Resource}}$) contribution. Using the AI and Physical Sciences paper taxonomy framework:

Primary Classification: Method

The dominant basis vector is Methodological because SubGrapher introduces a novel architecture that fundamentally changes the OCSR workflow from two-step reconstruction (image → structure → fingerprint) to single-step fingerprinting (image → visual fingerprint). The paper validates this approach through systematic comparison against state-of-the-art methods (MolGrapher, OSRA, DECIMER, MolScribe), demonstrating superior performance on specific tasks like retrieval and robustness to image quality degradation.

Secondary Classification: Resource

The paper makes non-negligible resource contributions by releasing:

- Code and model weights on GitHub and HuggingFace

- Five new visual fingerprinting benchmark datasets for molecule retrieval tasks

- Comprehensive functional group knowledge base (1,534 substructures)

Motivation: Extracting Complex Structures from Noisy Images

The motivation tackles a fundamental challenge in chemical informatics: extracting molecular information from the vast amounts of unstructured scientific literature, particularly patents. Millions of molecular structures exist only as images in these documents, making them inaccessible for computational analysis, database searches, or machine learning applications.

Traditional Optical Chemical Structure Recognition (OCSR) tools attempt to fully reconstruct molecular graphs from images, converting them into machine-readable formats like SMILES. However, these approaches face two critical limitations:

- Brittleness to image quality: Poor resolution, noise, or unconventional drawing styles frequently cause complete failure

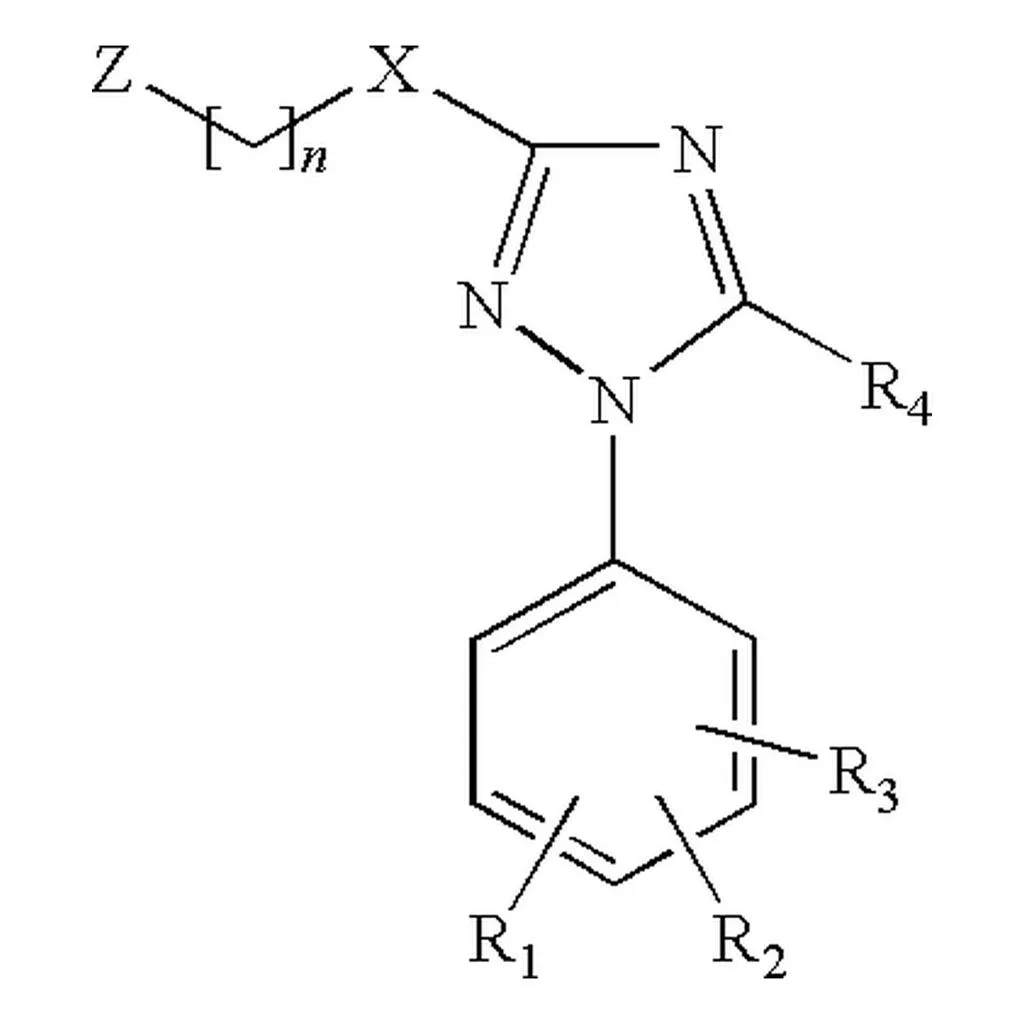

- Inability to handle complex structures: Markush structures, generic molecular templates with variable R-groups commonly used in patents, cannot be processed by conventional OCSR methods

The key insight driving SubGrapher is that full molecular reconstruction may be unnecessary for many applications. For tasks like database searching, similarity analysis, or document retrieval, a molecular fingerprint - a vectorized representation capturing structural features - is often sufficient. This realization opens up a new approach: bypass the fragile reconstruction step and create fingerprints directly from visual information.

Key Innovation: Direct Visual Fingerprinting

SubGrapher introduces a fundamentally different paradigm for extracting chemical information from images. It creates “visual fingerprints” through functional group recognition. The key innovations are:

Direct Image-to-Fingerprint Pipeline: SubGrapher eliminates the traditional two-step process (image → structure → fingerprint) by generating fingerprints directly from pixels. This single-stage approach avoids error accumulation from failed structure reconstructions and can handle images that would completely break conventional OCSR tools.

Dual Instance Segmentation Architecture: The system employs two specialized Mask-RCNN networks working in parallel:

- Functional group detector: Trained to identify 1,534 expert-defined functional groups using pixel-level segmentation masks

- Carbon backbone detector: Recognizes 27 common carbon chain patterns to capture the molecular scaffold

Using instance segmentation provides detailed spatial information and higher accuracy through richer supervision during training.

Extensive Functional Group Knowledge Base: The method leverages one of the most comprehensive open-source collections of functional groups, encompassing 1,534 substructures. These were systematically defined by:

- Starting with chemically logical atom combinations (C, O, S, N, B, P)

- Expanding to include relevant subgroups and variations

- Filtering based on frequency (appearing ~1,000+ times in PubChem)

- Manual curation with SMILES, SMARTS, and descriptive names

Substructure-Graph Construction: After detecting functional groups and carbon backbones, SubGrapher builds a connectivity graph where:

- Each node represents an identified substructure

- Edges connect substructures whose bounding boxes overlap (with 10% margin expansion)

- This graph captures both the chemical components and their spatial relationships

Substructure-based Visual Molecular Fingerprint (SVMF): The final output is a continuous, count-based fingerprint formally defined as a matrix $SVMF(m) \in \mathbb{R}^{n xn}$ where $n=1561$ (1,534 functional groups + 27 carbon backbones). The matrix is stored as a compressed upper triangular form:

Diagonal elements ($i = j$): Weighted count of substructure $i$ $$SVMF_{ii}(m) = h_1 \cdot \text{count}(s_i)$$ where $h_1 = 10$ is the diagonal weight hyperparameter.

Off-diagonal elements ($i \neq j$): Intersection coefficient based on shortest path distance $d$ in the substructure graph $$SVMF_{ij}(m) = h_2(d) \cdot \text{intersection}(s_i, s_j)$$ where the distance decay function $h_2(d)$ is:

- $d \leq 1$: weight = 2

- $d = 2$: weight = 2/4 = 0.5

- $d = 3$: weight = 2/16 = 0.125

- $d = 4$: weight = $2/256 \approx 0.0078$

- $d > 4$: weight = 0

Key properties:

- Functional groups receive higher weight than carbon chains in the graph construction

- Similarity between fingerprints calculated using Euclidean distance

- Resulting fingerprints are highly sparse (average 0.001% non-zero elements)

- Compressed storage enables efficient database searches

Markush Structure Compatibility: Unlike traditional OCSR methods that fail on generic structures, SubGrapher can process Markush structures by recognizing their constituent functional groups and creating meaningful fingerprints for similarity searches.

Experimental Validation and Benchmarks

The evaluation focused on demonstrating SubGrapher’s effectiveness across two critical tasks: accurate substructure detection and robust molecule retrieval from diverse image collections.

Substructure Detection Performance

SubGrapher’s ability to identify functional groups was tested on three challenging benchmarks that expose different failure modes of OCSR systems:

| Dataset | Size | Description | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| JPO | 341 images | Japanese Patent Office images | Low quality, noise, artifacts, non-standard drawing styles |

| USPTO-10K-L | 1,000 images | Large molecules (>70 atoms) | Scale variation, structural complexity, many functional groups |

| USPTO-Markush | 74 images | Generic Markush structures | Variable R-groups, abstract patterns, template representation |

Key findings:

JPO Dataset (Low-Quality Patent Images): SubGrapher achieved the highest Molecule Exact Match rate (83%), demonstrating robustness to image quality degradation that breaks traditional rule-based methods.

USPTO-10K-L (Large Molecules): The object detection approach handled scale variation better than conventional OCSR tools, achieving superior Substructure F1-scores on these challenging targets.

USPTO-Markush (Generic Structures): SubGrapher was the only method capable of processing these images, as traditional OCSR tools cannot handle generic molecular templates.

Qualitative analysis revealed that SubGrapher correctly identified functional groups in scenarios where other methods failed completely: images with captions, unconventional drawing styles, or significant quality degradation.

Visual Fingerprinting for Molecule Retrieval

The core application was evaluated using a retrieval task designed to simulate real-world database searching:

Benchmark Creation: Five benchmark datasets were constructed around structurally similar molecules (adenosine, camphor, cholesterol, limonene, and pyridine), each containing 500 similar molecular images.

Retrieval Task: Given a SMILES string as a query, the goal was to find the corresponding molecular image within the dataset of 500 visually similar structures. This tests whether the visual fingerprint can distinguish between closely related molecules.

Performance Comparison: SubGrapher significantly outperformed baseline methods, retrieving the correct molecule at an average rank of 95 out of 500. The key advantage was robustness—SubGrapher generates a unique fingerprint for every image, even with partial or uncertain predictions. In contrast, OCSR-based methods frequently fail to produce valid SMILES, making them unable to generate fingerprints for comparison.

Real-World Case Study: A practical demonstration involved searching a 54-page patent document containing 356 chemical images for a specific Markush structure. SubGrapher successfully located the target structure, highlighting its utility for large-scale document mining.

Training Data Generation

Since no public datasets existed with the required pixel-level mask annotations for functional groups, the researchers developed a comprehensive synthetic data generation pipeline:

Extended MolDepictor: They enhanced existing molecular rendering tools to create images from SMILES strings and generate corresponding segmentation masks for all substructures present in each molecule.

Markush Structure Rendering: The pipeline was extended to handle complex generic structures, creating training data for molecular templates that conventional tools cannot process.

Diverse Molecular Sources: Training molecules were sourced from both ChEMBL and PubChem to ensure broad chemical diversity and coverage of different structural families.

Results, Impact, and Limitations

- Superior Robustness to Image Quality: SubGrapher consistently outperformed traditional OCSR methods on degraded images, particularly the JPO patent dataset. While rule-based systems failed completely on poor-quality images, SubGrapher’s learned representations proved resilient to noise, artifacts, and unconventional drawing styles.

| Metric | SubGrapher | MolScribe | OSRA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-F1 (JPO) | 92 | 94 | 81 | SubGrapher comparable to SOTA on detection |

| M-EM (JPO) | 83 | 82 | 67 | SubGrapher wins on exact match for noisy images |

| Avg Retrieval Rank | ~95/500 | >100/500 | >100/500 | SubGrapher significantly better at finding correct molecule |

Effective Handling of Scale and Complexity: The instance segmentation approach successfully managed large molecules and complex structures where traditional graph-reconstruction methods struggled. The Substructure F1-scores on USPTO-10K-L and USPTO-Markush benchmarks demonstrated clear advantages for challenging molecular targets.

Breakthrough for Markush Structure Processing: SubGrapher represents the first practical solution for extracting information from Markush structures. These generic molecular templates appear frequently in patents but cannot be processed by conventional OCSR tools. This capability significantly expands the scope of automatically extractable chemical information from patent literature.

Robust Molecule Retrieval Performance: The visual fingerprinting approach achieved reliable retrieval performance (average rank 95/500) across diverse molecular families. The key advantage was consistency—SubGrapher generates meaningful fingerprints even from partial or uncertain predictions, while OCSR-based methods often fail to produce any usable output.

Practical Document Mining Capability: The successful identification of specific Markush structures within large patent documents (54 pages, 356 images) demonstrates real-world applicability for large-scale literature mining and intellectual property analysis.

Single-Stage Architecture Benefits: By eliminating the traditional image → structure → fingerprint pipeline, SubGrapher avoids error accumulation from failed molecular reconstructions. Every input image produces a fingerprint, making the system more reliable for batch processing of diverse document collections.

Limitations and Scope: The method remains focused on common organic functional groups and may struggle with inorganic chemistry, organometallic complexes, or highly specialized molecular classes not well-represented in the training data. The 1,534 functional groups, while extensive, represent a curated subset of chemical space.

The work establishes a new paradigm for chemical information extraction from images, demonstrating that direct fingerprint generation can be more robust and practical than traditional structure reconstruction approaches. SubGrapher’s ability to handle Markush structures and degraded images makes it particularly valuable for patent analysis and large-scale document mining, where traditional OCSR methods frequently fail. The approach suggests that task-specific learning (fingerprints for retrieval) can outperform general-purpose reconstruction methods in many practical applications.

Reproducibility Details

Data

Training Data Generation: The paper developed a custom synthetic data pipeline since no public datasets existed with pixel-level mask annotations for functional groups:

- Extended MolDepictor: Enhanced molecular rendering tool to generate both images and corresponding segmentation masks for all substructures

- Markush Structure Rendering: Pipeline extended to handle complex generic structures

- Source Molecules: ChEMBL and PubChem for broad chemical diversity

Evaluation Benchmarks:

- JPO Dataset: Real patent images with poor resolution, noise, and artifacts

- USPTO-10K-L: Large complex molecular structures

- USPTO-Markush: Generic structures with variable R-groups

- Retrieval Benchmarks: Five datasets (adenosine, camphor, cholesterol, limonene, pyridine), each with 500 similar molecular images

Models

Architecture: Dual instance segmentation system using Mask-RCNN

- Functional Group Detector: Mask-RCNN trained to identify 1,534 expert-defined functional groups

- Carbon Backbone Detector: Mask-RCNN trained to recognize 27 common carbon chain patterns

- Backbone Network: Not specified in paper (typically ResNet-50/101 or Swin Transformer for Mask-RCNN)

Functional Group Knowledge Base: 1,534 substructures systematically defined by:

- Starting with chemically logical atom combinations (C, O, S, N, B, P)

- Expanding to include relevant subgroups and variations

- Filtering based on frequency (appearing ~1,000+ times in PubChem)

- Manual curation with SMILES, SMARTS, and descriptive names

Algorithms

Functional Group Definition:

- 1,534 Functional Groups: Defined by manually curated SMARTS patterns

- Must contain heteroatoms (O, N, S, P, B)

- Frequency threshold: ~1,000+ occurrences in PubChem

- Systematically constructed from chemically logical atom combinations

- Manual curation with SMILES, SMARTS, and descriptive names

- 27 Carbon Backbones: Patterns of 3-6 carbon atoms (rings and chains) to capture molecular scaffolds

Substructure-Graph Construction:

- Detect functional groups and carbon backbones using Mask-RCNN models

- Build connectivity graph:

- Each node represents an identified substructure instance

- Edges connect substructures whose bounding boxes overlap

- Bounding boxes expanded by 10% of smallest box’s diagonal to ensure connectivity between adjacent groups

- Functional groups weighted higher than carbon chains in graph construction

SVMF Fingerprint Generation:

- Matrix form: $SVMF(m) \in \mathbb{R}^{n xn}$ where $n=1561$

- Stored as compressed sparse upper triangular matrix

- Diagonal elements: $SVMF_{ii} = h_1 \cdot \text{count}(s_i)$ where $h_1 = 10$

- Off-diagonal elements: $SVMF_{ij} = h_2(d) \cdot \text{intersection}(s_i, s_j)$ where:

- $h_2(d) = 2$ for $d \leq 1$

- $h_2(d) = 2/4^{(d-1)}$ for $d = 2, 3, 4$

- $h_2(d) = 0$ for $d > 4$

- Average sparsity: 0.001% non-zero elements

- Similarity metric: Euclidean distance between fingerprint vectors

Evaluation

Metrics:

- Substructure F1-score (S-F1): Harmonic mean of precision and recall for individual substructure detection across all molecules in the dataset

- Molecule Exact Match (M-EM): Percentage of molecules where S-F1 = 1.0 (all substructures correctly identified)

- Retrieval Rank: Average rank of ground truth molecule in candidate list of 500 similar structures when querying with SMILES fingerprint

Baselines: Compared against SOTA OCSR methods:

- Deep learning: MolScribe, MolGrapher, DECIMER

- Rule-based: OSRA

- Fingerprint methods: RDKit Daylight, MHFP (applied to OCSR outputs)

Hardware

Not specified in the paper. Training and inference hardware details are not provided in the main text or would be found in supplementary materials.

Implementation Gaps

The following details are not available in the paper and would require access to the code repository or supplementary information:

- Specific backbone architecture for Mask-RCNN (ResNet variant, Swin Transformer, etc.)

- Optimizer type (AdamW, SGD, etc.)

- Learning rate and scheduler

- Batch size and number of training epochs

- Loss function weights (box loss vs. mask loss)

- GPU/TPU specifications used for training

- Training time and computational requirements