Paper Information

Citation: Fang, X., Wang, J., Cai, X., Chen, S., Yang, S., Tao, H., Wang, N., Yao, L., Zhang, L., & Ke, G. (2025). MolParser: End-to-end Visual Recognition of Molecule Structures in the Wild (No. arXiv:2411.11098). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.11098

Publication: arXiv preprint (2025)

Additional Resources:

- MolParser-7M Dataset - 7M+ image-text pairs for OCSR

- MolParser-7M on HuggingFace - Dataset repository

- MolDet YOLO Detector - Object detection model for extracting molecular images from documents

Contribution: End-to-End OCSR and Real-World Resources

This is primarily a Method paper (see AI and Physical Sciences paper taxonomy), with a significant secondary contribution as a Resource paper.

Method contribution ($\Psi_{\text{Method}}$): The paper proposes a novel end-to-end architecture combining a Swin Transformer encoder with a BART decoder, and crucially introduces Extended SMILES (E-SMILES), a new syntactic extension to standard SMILES notation that enables representation of Markush structures, abstract rings, and variable attachment points found in patents. The work validates this method through extensive ablation studies and achieves state-of-the-art performance against prior OCSR systems.

Resource contribution ($\Psi_{\text{Resource}}$): The paper introduces MolParser-7M, the largest OCSR dataset to date (7.7M image-text pairs), and WildMol, a challenging benchmark of 20,000 manually annotated real-world molecular images. The construction of these datasets through an active learning data engine with human-in-the-loop validation represents significant infrastructure that enables future OCSR research.

Motivation: Unlocking Chemistry from Real-World Documents

The motivation stems from a practical problem in chemical informatics: vast amounts of chemical knowledge are locked in unstructured formats. Patents, research papers, and legacy documents depict molecular structures as images. This creates a barrier for large-scale data analysis and prevents Large Language Models from effectively understanding scientific literature in chemistry and drug discovery.

Existing OCSR methods struggle with real-world documents for two fundamental reasons:

- Representational limitations: Standard SMILES notation cannot capture complex structural templates like Markush structures, which are ubiquitous in patents. These structures define entire families of compounds using variable R-groups and abstract patterns, making them essential for intellectual property but impossible to represent with conventional methods.

- Data distribution mismatch: Real-world molecular images suffer from noise, inconsistent drawing styles, variable resolution, and interference from surrounding text. Models trained exclusively on clean, synthetically rendered molecules fail to generalize when applied to actual documents.

Novelty: E-SMILES and Human-in-the-Loop Data Engine

The novelty lies in a comprehensive system that addresses both representation and data quality challenges through four integrated contributions:

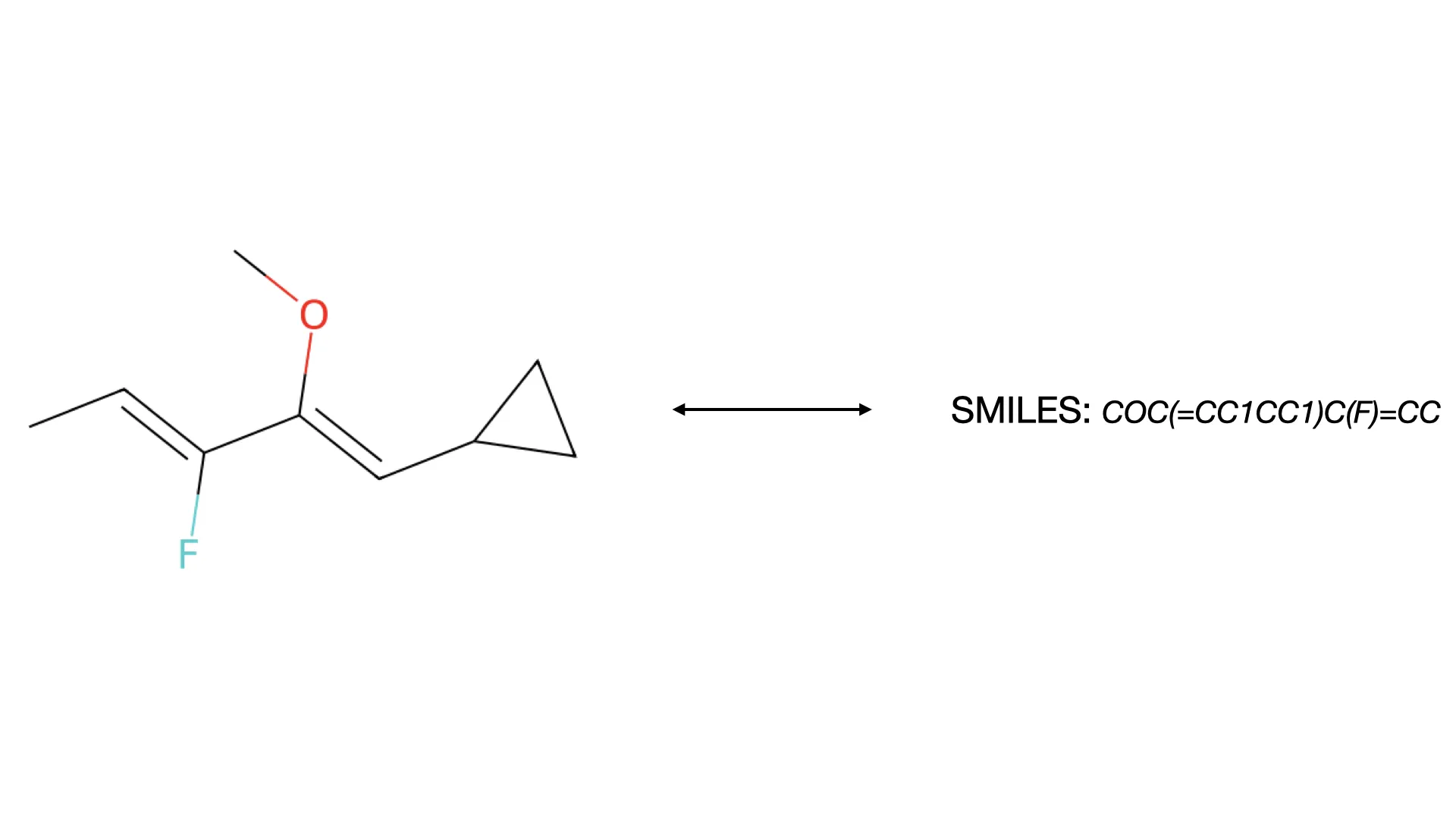

Extended SMILES (E-SMILES): A backward-compatible extension to the SMILES format that can represent complex structures previously inexpressible in standard chemical notations. E-SMILES uses a separator token

<sep>to delineate the core molecular structure from supplementary annotations. These annotations employ XML-like tags to encode Markush structures, polymers, abstract rings, and other complex patterns. Critically, the core structure remains parseable by standard cheminformatics tools like RDKit, while the supplementary tags provide a structured, LLM-friendly format for capturing edge cases.MolParser-7M Dataset: The largest publicly available OCSR dataset, containing over 7 million image-text pairs. What distinguishes this dataset is both its scale and its composition. It includes 400,000 “in-the-wild” samples (molecular images extracted from actual patents and scientific papers) and subsequently curated by human annotators. This real-world data addresses the distribution mismatch problem directly by exposing the model to the same noise, artifacts, and stylistic variations it encounters in production.

Human-in-the-Loop Data Engine: A systematic approach to collecting and annotating real-world training data. The pipeline begins with an object detection model that extracts molecular images from over a million PDF documents. An active learning algorithm then identifies the most informative samples (those where the current model struggles) for human annotation. The model pre-annotates these images, and human experts review and correct them. This creates an iterative improvement cycle: annotate, train, identify new challenging cases, repeat.

Efficient End-to-End Architecture: The model treats OCSR as an image captioning problem. A Swin-Transformer vision encoder extracts visual features, a simple MLP compresses them, and a BART decoder generates the E-SMILES string autoregressively. The model minimizes the standard negative log-likelihood of the target E-SMILES token sequence $y$ given the sequence history and input image $x$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{L} = -\sum_{t=1}^{T} \log P(y_t \mid y_{<t}, x; \theta) \end{aligned} $$

The training strategy employs curriculum learning, starting with simple molecules and gradually introducing complexity and heavier data augmentation.

Experimental Setup: Two-Stage Training and Benchmarking

The evaluation focused on demonstrating that MolParser generalizes to real-world documents:

Two-Stage Training Protocol: The model underwent a systematic training process:

- Pre-training: Initial training on millions of synthetic molecular images using curriculum learning. The curriculum progresses from simple molecules to complex structures while gradually increasing data augmentation intensity (blur, noise, perspective transforms).

- Fine-tuning: Subsequent training on 400,000 curated real-world samples extracted from patents and papers. This fine-tuning phase is critical for adapting to the noise and stylistic variations of actual documents.

Benchmark Evaluation: The model was evaluated on multiple standard OCSR benchmarks to establish baseline performance on clean data. These benchmarks test recognition accuracy on well-formatted molecular diagrams.

Real-World Document Analysis: The critical test involved applying MolParser to molecular structures extracted directly from scientific documents. This evaluation measures the gap between synthetic benchmark performance and real-world applicability (the core problem the paper addresses).

Ablation Studies: Experiments isolating the contribution of each component:

- The impact of real-world training data versus synthetic-only training

- The effectiveness of curriculum learning versus standard training

- The value of the human-in-the-loop annotation pipeline versus random sampling

- The necessity of E-SMILES extensions for capturing complex structures

Outcomes and Empirical Findings

Performance on Benchmarks: MolParser improves upon previous OCSR methods on both standard benchmarks and real-world documents. The performance gap is particularly pronounced on real-world data, validating the core hypothesis that training on actual document images is essential for practical deployment. On WildMol-10k, MolParser-Base achieved 76.9% accuracy, significantly outperforming MolScribe (66.4%) and MolGrapher (45.5%).

Real-World Data is Critical: Models trained exclusively on synthetic data show substantial performance degradation when applied to real documents. The 400,000 in-the-wild training samples bridge this gap, demonstrating that data quality and distribution matching matter as much as model architecture. Ablation experiments showed synthetic-only training achieved only 22.4% accuracy on WildMol versus 76.9% with real-world fine-tuning.

E-SMILES Enables Broader Coverage: The extended representation successfully captures molecular structures that were previously inexpressible, particularly Markush structures from patents. This dramatically expands the scope of what can be automatically extracted from chemical literature.

Human-in-the-Loop Scales Efficiently: The active learning pipeline reduces annotation time by up to 90% while maintaining high quality. This approach makes it feasible to curate large-scale, high-quality datasets for specialized domains where expert knowledge is expensive.

Speed and Accuracy: The end-to-end architecture achieves both high accuracy and fast inference, making it practical for large-scale document processing. MolParser-Base processes 40 images per second on RTX 4090D, while the Tiny variant achieves 131 FPS. The direct image-to-text approach avoids the error accumulation of multi-stage pipelines.

The work establishes that practical OCSR requires more than architectural innovations. It demands careful attention to data quality, representation design, and the distribution mismatch between synthetic training data and real-world applications. The combination of E-SMILES, the MolParser-7M dataset, and the human-in-the-loop data engine provides a template for building robust vision systems in scientific domains where clean training data is scarce but expert knowledge is available.

Reproducibility Details

Data

The training data is split into a massive synthetic pre-training set and a curated fine-tuning set.

Training Data Composition (MolParser-7M):

| Purpose | Dataset Name | Size | Composition / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | MolParser-7M (Synthetic) | ~7.3M | Markush-3M (40%), ChEMBL-2M (27%), Polymer-1M (14%), PAH-600k (8%), BMS-360k (5%). Generated via RDKit/Indigo with randomized styles. |

| Fine-tuning | MolParser-SFT-400k | 400k | Real images from patents/papers selected via active learning (confidence filtering 0.6-0.9) and manually annotated. 66% real molecules from PDFs, 34% synthetic. |

| Fine-tuning | MolParser-Gen-200k | 200k | Subset of synthetic data kept to prevent catastrophic forgetting. |

| Fine-tuning | Handwrite-5k | 5k | Handwritten molecules from Img2Mol to support hand-drawn queries. |

- Sources: 1.2M patents and scientific papers (PDF documents)

- Extraction: MolDet (YOLO11-based detector) identified ~20M molecular images, deduplicated to ~4M candidates

- Selection: Active learning ensemble (5-fold models) identified high-uncertainty samples for annotation

- Annotation: Human experts corrected model pre-annotations (90% time savings vs. from-scratch annotation)

Test Benchmarks:

| Benchmark | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| USPTO-10k | 10,000 | Standard synthetic benchmark |

| Maybridge UoB | - | Synthetic molecules |

| CLEF-2012 | - | Patent images |

| JPO | - | Japanese patent office |

| ColoredBG | - | Colored background molecules |

| WildMol-10k | 10,000 | Ordinary molecules cropped from real PDFs (new) |

| WildMol-10k-M | 10,000 | Markush structures (significantly harder, new) |

Algorithms

Extended SMILES (E-SMILES) Encoding:

- Format:

SMILES<sep>EXTENSIONwhere<sep>separates core structure from supplementary annotations - Extensions use XML-like tags:

<a>index:group</a>for substituents/variable groups (Markush structures)<r>for variable attachment points<c>for abstract rings<dum>for connection points

- Backward compatible: Core SMILES parseable by RDKit; extensions provide structured format for edge cases

Curriculum Learning Strategy:

- Phase 1: No augmentation, simple molecules (<60 tokens)

- Phase 2: Gradually increase augmentation intensity and sequence length

- Progressive complexity allows stable training on diverse molecular structures

Active Learning Data Selection:

- Train 5 model folds on current dataset

- Compute pairwise Tanimoto similarity of predictions on candidate images

- Select samples with confidence scores 0.6-0.9 for human review (highest learning value)

- Human experts correct model pre-annotations

- Iteratively expand training set with hard samples

Data Augmentations:

- RandomAffine (rotation, scale, translation)

- JPEGCompress (compression artifacts)

- InverseColor (color inversion)

- SurroundingCharacters (text interference)

- RandomCircle (circular artifacts)

- ColorJitter (brightness, contrast variations)

Models

The architecture follows a standard Image Captioning (Encoder-Decoder) paradigm.

Architecture Specifications:

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Vision Encoder | Swin Transformer (ImageNet pretrained) |

| - Tiny variant | 66M parameters, $224 \x224$ input |

| - Small variant | 108M parameters |

| - Base variant | 216M parameters, $384 \x384$ input |

| Connector | 2-layer MLP reducing channel dimension by half |

| Text Decoder | BART-Decoder (12 layers, 16 attention heads) |

Training Configuration:

| Setting | Pre-training | Fine-tuning |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | 8x NVIDIA RTX 4090D GPUs | 8x NVIDIA RTX 4090D GPUs |

| Optimizer | AdamW | AdamW |

| Learning Rate | $1 \x10^{-4}$ | $5 \x10^{-5}$ |

| Weight Decay | $1 \x10^{-2}$ | $1 \x10^{-2}$ |

| Scheduler | Cosine with warmup | Cosine with warmup |

| Epochs | 20 | 4 |

| Label Smoothing | 0.01 | 0.005 |

Curriculum Learning Schedule (Pre-training):

- Starts with simple molecules (<60 tokens, no augmentation)

- Gradually adds complexity and augmentation (blur, noise, perspective transforms)

- Enables stable learning across diverse molecular structures

Evaluation

Metrics: Exact match accuracy on predicted E-SMILES strings (character-level exact match)

Key Results:

| Metric | MolParser-Base | MolScribe | MolGrapher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WildMol-10k | 76.9% | 66.4% | 45.5% | Real-world patent/paper crops |

| USPTO-10k | 94.5% | 96.0% | 93.3% | Synthetic benchmark |

| Throughput (FPS) | 39.8 | 16.5 | 2.2 | Measured on RTX 4090D |

Additional Performance:

- MolParser-Tiny: 131 FPS on RTX 4090D (66M params)

- Real-world vs. synthetic gap: Fine-tuning on MolParser-SFT-400k closed the performance gap between clean benchmarks and in-the-wild documents

Ablation Findings:

| Factor | Impact |

|---|---|

| Real-world training data | Substantial accuracy gains on documents vs. synthetic-only training (22.4% → 76.9% on WildMol) |

| Curriculum learning | Outperforms standard training, especially for complex molecules |

| Active learning selection | More effective than random sampling for annotation budget |

| E-SMILES extensions | Essential for Markush structure recognition (impossible with standard SMILES) |

| Dataset scale | Larger pre-training dataset (7M vs 300k) significantly improves generalization |

Hardware

- Training: 8x NVIDIA RTX 4090D GPUs

- Inference: Single RTX 4090D sufficient for real-time processing

- Training time: 20 epochs pre-training + 4 epochs fine-tuning (specific duration not reported)

Citation

@misc{fang2025molparser,

title={MolParser: End-to-end Visual Recognition of Molecule Structures in the Wild},

author={Fang, Xi and Wang, Jiankun and Cai, Xiaochen and Chen, Shangqian and Yang, Shuwen and Tao, Haoyi and Wang, Nan and Yao, Lin and Zhang, Linfeng and Ke, Guolin},

year={2025},

eprint={2411.11098},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CV},

doi={10.48550/arXiv.2411.11098}

}