Paper Information

Citation: Valko, A. T., & Johnson, A. P. (2009). CLiDE Pro: The Latest Generation of CLiDE, a Tool for Optical Chemical Structure Recognition. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 49(4), 780-787. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci800449t

Publication: Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2009

Contribution: Robust Algorithmic Pipeline for OCSR

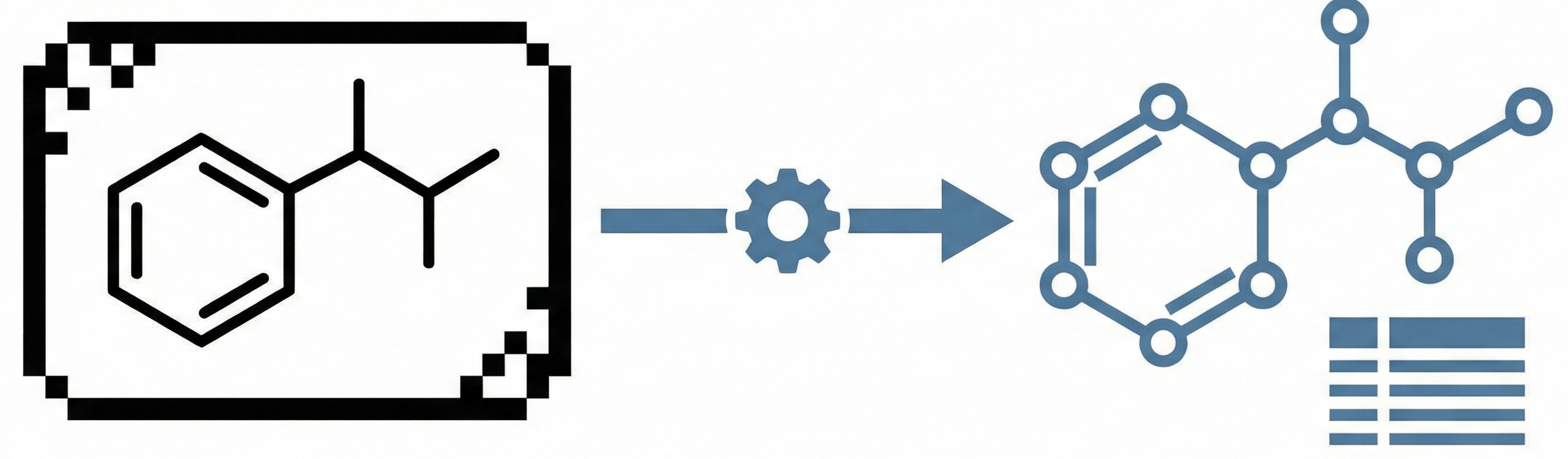

This is primarily a Method ($\Psi_{\text{Method}}$) paper, as it proposes a specific algorithmic architecture (CLiDE Pro) for converting raster images of chemical structures into connection tables. It details the procedural steps for segmentation, vectorization, and graph reconstruction.

It also has a secondary Resource ($\Psi_{\text{Resource}}$) contribution, as the authors compile and release a validation set of 454 real-world images to serve as a community benchmark for OCSR systems.

Motivation: Bridging the Gap Between Legacy Document Images and Machine-Readable Chemistry

While modern chemical drawing software captures structural information explicitly, the vast majority of legacy and current chemical literature (journals, patents, reports) exists as images or PDF documents. These images are human-readable but lack the semantic “connection table” data required for chemical databases and software. Manual redrawing is time-consuming and error-prone. Therefore, there is a critical need for efficient Optical Chemical Structure Recognition (OCSR) systems to automate this extraction.

Novelty: Integrated Document Segmentation and Ambiguity Resolution Heuristics

CLiDE Pro introduces several algorithmic improvements over its predecessor (CLiDE) and contemporary tools:

- Integrated Document Segmentation: Unlike page-oriented systems, it processes whole documents to link information across pages.

- Robust “Difficult Feature” Handling: It implements specific heuristic rules to resolve ambiguities in crossing bonds (bridged structures), which are often misinterpreted as carbon atoms in other systems.

- Generic Structure Interpretation: It includes a module to parse “generic” (Markush) structures by matching R-group labels in the diagram with text-based definitions found in the document.

- Ambiguity Resolution: It uses context-aware rules to distinguish between geometrically similar features, such as vertical lines representing bonds vs. the letter ’l’ in ‘Cl’.

Methodology and Benchmarking on Real-World Data

The authors conducted a systematic validation on a dataset of 454 images containing 519 structure diagrams.

- Source Material: Images were extracted from published materials (journals, patents), ensuring “real artifacts” like noise and scanning distortions were present.

- Automation: The test was fully automated without human intervention.

- Metrics: The primary metric was the “success rate,” defined as the correct reconstruction of the molecule’s connection table. They also performed fine-grained error analysis on specific features (e.g., atom labels, dashed bonds, wavy bonds).

Results: High Topological Accuracy and Persistent OCR Challenges

- High Accuracy: The system achieved a 89.79% retrieval rate (466/519 molecules correctly reconstructed).

- Robustness on Primitives: Solid straight bonds were recognized with 99.92% accuracy.

- Key Failure Modes: The majority of errors (58 cases) occurred in atom label construction, specifically when labels touched nearby bonds or other artifacts, causing OCR failures.

- Impact: The study demonstrated that handling “difficult” drawing features like crossing bonds and bridged structures significantly reduces topological errors. The authors released the test set to encourage standardized benchmarking in the OCSR field.

Reproducibility Details

Data

The authors utilized a custom dataset designed to reflect real-world noise.

| Purpose | Dataset | Size | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation | CLiDE Pro Validation Set | 454 images (519 structures) | Extracted from scanned journals and PDFs. Includes noise/artifacts. Available in Supporting Information. |

Algorithms

The CLiDE Pro pipeline consists of five distinct phases. To replicate this system, one would need to implement:

Image Binarization:

- Input images are binarized using a threshold-based technique to separate foreground (molecule) from background.

- Connected Component Analysis (CCA): A non-recursive scan identifies connected components (CCs) and generates interpixel contours (using N, S, E, W directions).

Document Segmentation:

- Layout Analysis: Uses a bottom-up approach building a tree structure. It treats CCs as graph vertices and distances as edges.

- Clustering: A minimal-cost spanning tree (Kruskal’s algorithm) groups CCs into words, lines, and blocks.

- Classification: CCs are classified (Character, Dash, Line, Graphics, Noise) based on size thresholds derived from statistical image analysis.

Vectorization:

- Contour Approximation: Uses a method similar to Sklansky and Gonzalez to approximate contours into polygons.

- Vector Formation: Long polygon sides become straight lines; short consecutive sides become curves. Opposing borders of a line are matched to define the bond vector.

- Wavy Bonds: Detected by finding groups of short vectors lying on a straight line.

- Dashed Bonds: Detected using the Hough transform to find collinear or parallel dashes.

Atom Label Construction:

- OCR: An OCR engine (filtering + topological analysis) interprets characters.

- Grouping: Characters are grouped into words based on horizontal and vertical proximity (for vertical labels).

- Superatom Lookup: Labels are matched against a database of elements, functional groups, and R-groups. Unknown linear formulas (e.g., $\text{CH}_2\text{CH}_2\text{OH}$) are parsed.

Graph Reconstruction:

- Connection Logic: Bond endpoints are joined to atoms if they are within a distance threshold and “point toward” the label.

- Implicit Carbons: Unconnected bond ends are joined if close; parallel bonds merge into double/triple bonds.

- Crossing Bonds: Rules check proximity, length, and ring membership to determine if crossing lines are valid atoms or 3D visual artifacts.

Generic Structure Interpretation:

- Text Mining: A lexical/syntactic analyzer extracts R-group definitions (e.g., “R = Me or H”) from text blocks.

- Matching: The system attempts to match R-group labels in the diagram with the parsed text definitions.

Models

- OCR Engine: The system relies on a customized OCR engine capable of handling rotation and chemical symbols, though the specific architecture (neural vs. feature-based) is not detailed beyond “topological and geometrical feature analysis”.

- Superatom Database: A lookup table containing elements, common functional groups, and R-group labels.

Evaluation

The evaluation focused on the topological correctness of the output.

| Metric | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Total Success Rate | 89.79% | 466/519 structures perfectly reconstructed. |

| Atom Label Accuracy | 98.54% | 3923/3981 labels correct. Main error source: labels touching bonds. |

| Solid Bond Accuracy | >99.9% | 16061/16074 solid bonds correct. |

| Dashed Bond Accuracy | 98.37% | 303/308 dashed bonds correct. |

Hardware

- Requirements: Unspecified; described as efficient.

- Performance: The system processed the complex Palytoxin structure “within a few seconds”. This implies low computational overhead suitable for standard desktop hardware of the 2009 era.

Citation

@article{valkoCLiDEProLatest2009,

title = {CLiDE Pro: The Latest Generation of CLiDE, a Tool for Optical Chemical Structure Recognition},

author = {Valko, Aniko T. and Johnson, A. Peter},

journal = {Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling},

volume = {49},

number = {4},

pages = {780--787},

year = {2009},

doi = {10.1021/ci800449t}

}