Paper Information

Citation: Weininger, D. (1988). SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences, 28(1), 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00057a005

Publication: Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences, 1988

Additional Resources:

- SMILES notation overview - Modern usage summary

- Converting SMILES to 2D images - Practical visualization tutorial

Core Contribution: A String-Based Molecular Notation

This is a Method paper that introduces a novel notation system for representing chemical structures as text strings. It establishes the encoding rules and input conventions for SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), while explicitly deferring the canonicalization algorithm to subsequent papers in the series.

The Computational Complexity of Chemical Information in the 1980s

As computers became central to chemical information processing in the 1980s, the field faced a fundamental problem: existing line notations were either too complex for chemists to use practically or too limited for computational applications. Previous systems required extensive training to write correctly and were prone to errors.

The goal was ambitious: create a system that could represent any molecule as a simple text string, making it both human-readable and machine-efficient. This would enable compact database storage, fast processing, and easy exchange between software systems.

Separating Input Rules from Canonicalization

Weininger’s key insight was to separate the problem into two parts: create simple, flexible rules that chemists could easily learn for input, while deferring to the computer the complex task of generating a unique, canonical representation. This division of labor made SMILES both practical and powerful.

The specific innovations include:

- Simple input rules - Chemists could write molecules intuitively (e.g.,

CCOorOCCfor ethanol) - Ring closure notation - Breaking one bond and marking ends with matching digits

- Implicit hydrogens - Automatic calculation based on standard valences keeps strings compact

- Algorithmic aromaticity detection - Automatic recognition of aromatic systems from Kekulé structures

- Human-readable output - Unlike binary formats, SMILES strings are readable and debuggable

Important scope note: This first paper in the series establishes the input syntax and encoding rules. The canonicalization algorithm (how to generate unique SMILES) is explicitly stated as the subject of following papers: “specification of isomerisms, substructures, and unique SMILES generation are the subjects of following papers.”

Demonstrating Notation Rules Across Molecular Classes

The paper is primarily a specification document establishing notation rules. The methodology is demonstrated through worked examples showing how to encode various molecular structures:

- Basic molecules: Ethane (

CC), ethylene (C=C), acetylene (C#C) - Branches: Isobutyric acid (

CC(C)C(=O)O) - Rings: Cyclohexane (

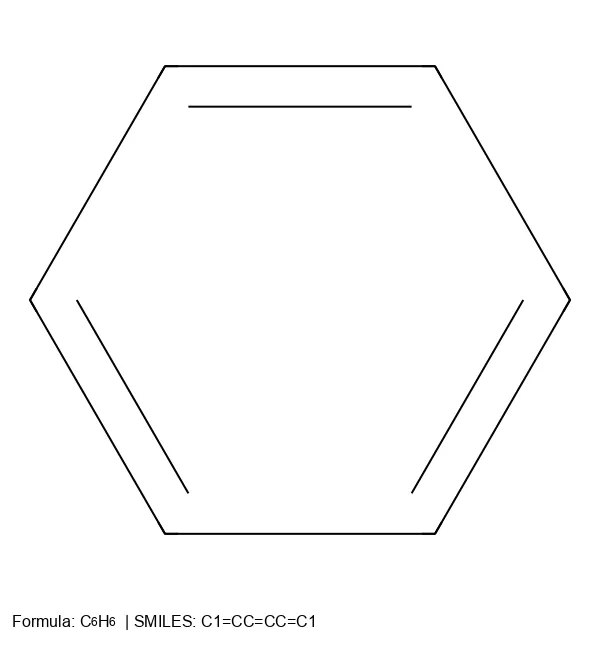

C1CCCCC1), benzene (c1ccccc1) - Aromatic systems: Tropone (

O=c1ccccc1), quinone (showing exocyclic bond effects) - Complex structures: Morphine (40 characters vs 1000-2000 for connection tables)

- Edge cases: Salts, isotopes, charged species, tautomers

Performance comparisons are mentioned qualitatively: SMILES processing was approximately 100 times faster than traditional connection table methods on the hardware of the era (1988), with dramatic reductions in storage space.

Performance and Practical Viability

The paper successfully establishes SMILES as a practical notation system with several key outcomes:

Practical benefits:

- Compactness: 40 characters for morphine vs 1000-2000 for connection tables

- Speed: ~100x faster processing than traditional methods

- Accessibility: Simple enough for chemists to learn without extensive training

- Machine-friendly: Efficient parsing and string-based operations

Design principles validated:

- Separating user input from canonical representation makes the system both usable and rigorous

- Implicit hydrogens reduce string length without loss of information

- Ring closure notation with digit markers is more intuitive than complex graph syntax

- Automatic aromaticity detection handles most cases correctly

Acknowledged limitations:

- Canonicalization algorithm not included in this paper

- Stereochemistry handling deferred to subsequent papers

- Some edge cases (like unusual valence states) require explicit specification

The paper concludes by positioning SMILES as a foundation for database storage, substructure searching, and chemical informatics applications - a vision that proved accurate as SMILES became one of the most widely used molecular representations in computational chemistry.

Reproducibility Details

To implement the method described in this paper, the following look-up tables and algorithms are required. Note: These details are critical for replication but are often glossed over in high-level summaries.

1. The Valence Look-Up Table

To calculate implicit hydrogens, the system assumes the “lowest normal valence” greater than or equal to the explicit bond count. The paper explicitly defines these valences:

| Element | Allowed Valences |

|---|---|

| B | 3 |

| C | 4 |

| N | 3, 5 |

| O | 2 |

| P | 3, 5 |

| S | 2, 4, 6 |

| F, Cl, Br, I | 1 |

Example: For sulfur in $\text{H}_2\text{SO}_4$, the explicit bond count is 6 (four oxygens), so the system uses valence 6 with zero implicit hydrogens. Without knowing S allows valence 6, the algorithm would fail.

2. Explicit Hydrogen Requirements

The paper lists exactly three cases where hydrogen must be explicitly specified:

- Hydrogen connected to zero atoms (rare edge case)

- Hydrogen connected to other hydrogen (molecular hydrogen, $\text{H}_2$, written as

[H][H]) - Hydrogen connected to more than one atom (bridging hydrogens)

- Isotopic hydrogen (deuterium

[2H], tritium[3H])

For all other cases, hydrogens are implicit and calculated from the valence table.

3. Ring Closure Notation

Standard SMILES supports single digits 1-9 for ring closures. For rings numbered 10 and higher, the notation requires a percent sign prefix:

- Ring closures 1-9:

C1CCCCC1 - Ring closures 10+:

C%10CCCCC%10,C2%13%24(ring 2, ring 13, ring 24)

Without this rule, a parser would fail on large polycyclic structures.

4. Aromaticity Detection Algorithm

The system uses an algorithmic version of Hückel’s Rule ($4N+2$ π-electrons). The “excess electron” count for the aromatic system is determined by these rules:

Carbon contribution:

- C in aromatic ring: Contributes 1 electron

- C double-bonded to exocyclic electronegative atom (e.g., $\text{C}=\text{O}$ in quinone): Contributes 0 electrons (the carbon “loses” its electron to the oxygen)

Heteroatom contribution:

- O, S in ring: Contributes 2 electrons (lone pair)

- N in ring: Contributes 1 electron (pyridine-like) or 2 electrons (pyrrole-like, must have explicit hydrogen

[nH])

Charge effects:

- Positive charge: Reduces electron count by 1

- Negative charge: Increases electron count by 1

Critical example - Quinone:

O=C1C=CC(=O)C=C1

Quinone has 6 carbons in the ring, but the two carbons bonded to exocyclic oxygens contribute 0 electrons each. The four remaining carbons contribute 4 electrons total (not 6), so quinone is not aromatic by this algorithm. This exocyclic bond rule is essential for correct aromaticity detection.

Aromatic ring test:

- All atoms must be sp² hybridized

- Count excess electrons using the rules above

- Calculate whether the system complies with Hückel’s parity rule constraint: $$ \text{Excess Electrons} \equiv 2 \pmod 4 \iff \text{Excess Electrons} = 4N + 2 $$ If the electron count satisfies this property for some integer $N$, the ring is determined to be aromatic.

Encoding Rules Reference

The following sections provide a detailed reference for the six fundamental SMILES encoding rules. These are the rules a user would apply when writing SMILES strings.

1. Atoms

Atoms use their standard chemical symbols. Elements in the “organic subset” (B, C, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, I) can be written directly when they have their most common valence - so C automatically means a carbon with enough implicit hydrogens to satisfy its valence.

Everything else goes in square brackets: [Au] for gold, [NH4+] for ammonium ion, or [13C] for carbon-13. Aromatic atoms get lowercase letters: c for aromatic carbon in benzene.

2. Bonds

Bond notation is straightforward:

-for single bonds (usually omitted)=for double bonds#for triple bonds:for aromatic bonds (also usually omitted)

So CC and C-C both represent ethane, while C=C is ethylene.

3. Branches

Branches use parentheses, just like in mathematical expressions. Isobutyric acid becomes CC(C)C(=O)O - the main chain is CC C(=O)O with a methyl (C) branch.

4. Rings

This is where SMILES gets clever. You break one bond and mark both ends with the same digit. Cyclohexane becomes C1CCCCC1 - the 1 connects the first and last carbon, closing the ring.

You can reuse digits for different rings in the same molecule, making complex structures manageable.

5. Disconnected Parts

Salts and other disconnected structures use periods. Sodium phenoxide: [Na+].[O-]c1ccccc1. The order doesn’t matter - you’re just listing the separate components.

6. Aromaticity

Aromatic rings can be written directly with lowercase letters. Benzoic acid becomes c1ccccc1C(=O)O. The system can also detect aromaticity automatically from Kekulé structures, so C1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O works just as well.

Simplified Subset for Organic Chemistry

Weininger recognized that most chemists work primarily with organic compounds, so he defined a simplified subset that covers the vast majority of cases. For organic molecules, you only need four rules:

- Atoms: Use standard symbols (C, N, O, etc.)

- Multiple bonds: Use

=and#for double and triple bonds - Branches: Use parentheses

() - Rings: Use matching digits

This “basic SMILES” covers probably 90% of what most chemists encounter daily, making the system immediately accessible without having to learn all the edge cases.

Design Decisions and Edge Cases

Beyond the basic rules, the paper established several important conventions for handling ambiguous cases:

Hydrogen Handling

Hydrogens are usually implicit - the system calculates how many each atom needs based on standard valences. So C represents CH₄, N represents NH₃, and so on. This keeps strings compact and readable.

Explicit hydrogens only appear in special cases: when hydrogen connects to multiple atoms, when you need to specify an exact count, or in isotopic specifications like [2H] for deuterium.

Bond Representation

The paper made an important choice about how to represent bonds in ambiguous cases. For example, nitro groups could be written as charge-separated C[N+]([O-])[O-] or with double bonds CN(=O)=O. Weininger chose to prefer covalent bonds when possible, keeping the topology symmetric and avoiding unusual charges.

However, when covalent representation would require unusual valences, charge separation is preferred. Diazomethane becomes C=[N+]=[N-] to avoid forcing carbon into an unrealistic valence state.

Tautomers

SMILES doesn’t try to be too clever about tautomers - it represents exactly what you specify. So 2-pyridone can be written as either the enol form Oc1ncccc1 or the keto form O=c1[nH]cccc1. The system won’t automatically convert between them.

This explicit approach means you need to decide which tautomeric form to represent, but it also means the notation precisely captures what you intend.

Aromaticity Detection

One of the most sophisticated parts of the original system was automatic aromaticity detection. The algorithm uses an extended Hückel rule: a ring is aromatic if all atoms are sp² hybridized and it contains 4N+2 π-electrons.

This means you can input benzene as the Kekulé structure C1=CC=CC=C1 and the system will automatically recognize it as aromatic and convert it to c1ccccc1. The algorithm handles complex cases like tropone (O=c1ccccc1) and correctly identifies them as aromatic.

Aromatic Nitrogen

The system makes an important distinction for nitrogen in aromatic rings. Pyridine-type nitrogen (like in pyridine itself) is written as n and has no attached hydrogens. Pyrrole-type nitrogen has an attached hydrogen that must be specified explicitly: [nH]1cccc1 for pyrrole.

This distinction captures the fundamental difference in electron contribution between these two nitrogen types in aromatic systems.

Impact and Legacy

Nearly four decades later, SMILES remains one of the most important file formats in computational chemistry. The notation became the foundation for:

- Database storage - Compact, searchable molecular representations

- Substructure searching - Pattern matching in chemical databases

- Property prediction - Input format for QSAR models

- Chemical informatics - Standard exchange format between software

- Modern ML - Text-based representation for neural networks

While newer approaches like SELFIES have addressed some limitations (like the possibility of invalid strings), SMILES’ combination of simplicity and power has made it enduringly useful.

The paper established both a notation system and a design philosophy: chemical informatics tools should be powerful enough for computers while remaining accessible to working chemists. That balance remains relevant today as we develop new molecular representations for machine learning and AI applications.