A New Standard for Nanoinformatics

This is a Theory/Systematization paper that proposes a new Resource standard: the NInChI. It addresses a fundamental limitation in nanoinformatics. The result of a collaborative process (a “Request for Comments” or “RFC”), this work uses six detailed case studies to systematically develop a hierarchical, machine-readable notation for complex nanomaterials that could work across experimental research, regulatory frameworks, and computational modeling.

The Breakdown of Traditional Chemical Identifiers

Chemoinformatics has fantastic tools for representing small molecules: SMILES strings, InChI identifiers, and standardized databases that make molecular data searchable and shareable. But when you step into nanotechnology, everything breaks down.

Consider trying to describe a gold nanoparticle with a silica shell and organic surface ligands. How do you capture:

- The gold core composition and size

- The silica shell thickness and interface

- The surface chemistry and ligand density

- The overall shape and morphology

There’s simply no standardized way to represent this complexity in a machine-readable format. This creates massive problems for:

- Data sharing between research groups

- Regulatory assessment where precise identification matters

- Computational modeling that needs structured input

- Database development and search capabilities

Without a standard notation, nanomaterials research suffers from the same data fragmentation that plagued small molecule chemistry before SMILES existed.

The Five-Tier NInChI Hierarchy

The authors propose NInChI (Nanomaterials InChI), a layered extension to the existing InChI system. The clever insight is organizing nanomaterial description from the inside out, like describing an onion with a five-tier hierarchy:

- Tier 1: Chemical Core: What’s the fundamental composition? Gold? Silver? Carbon nanotube?

- Tier 2: Morphology: What shape and size? Spherical nanoparticle? Rod? 2D sheet?

- Tier 3: Surface Properties: What’s the surface like? Charge, roughness, hydrophobicity?

- Tier 4: Surface Chemistry: How are things attached? Covalent bonds? Physical adsorption?

- Tier 5: Surface Ligands: What molecules are on the surface and how many?

This hierarchy captures the essential information needed to distinguish between different nanomaterials while building on familiar chemical concepts.

Testing the Standard: Six Case Studies

The authors tested their concept against six real-world case studies to identify what actually matters in practice.

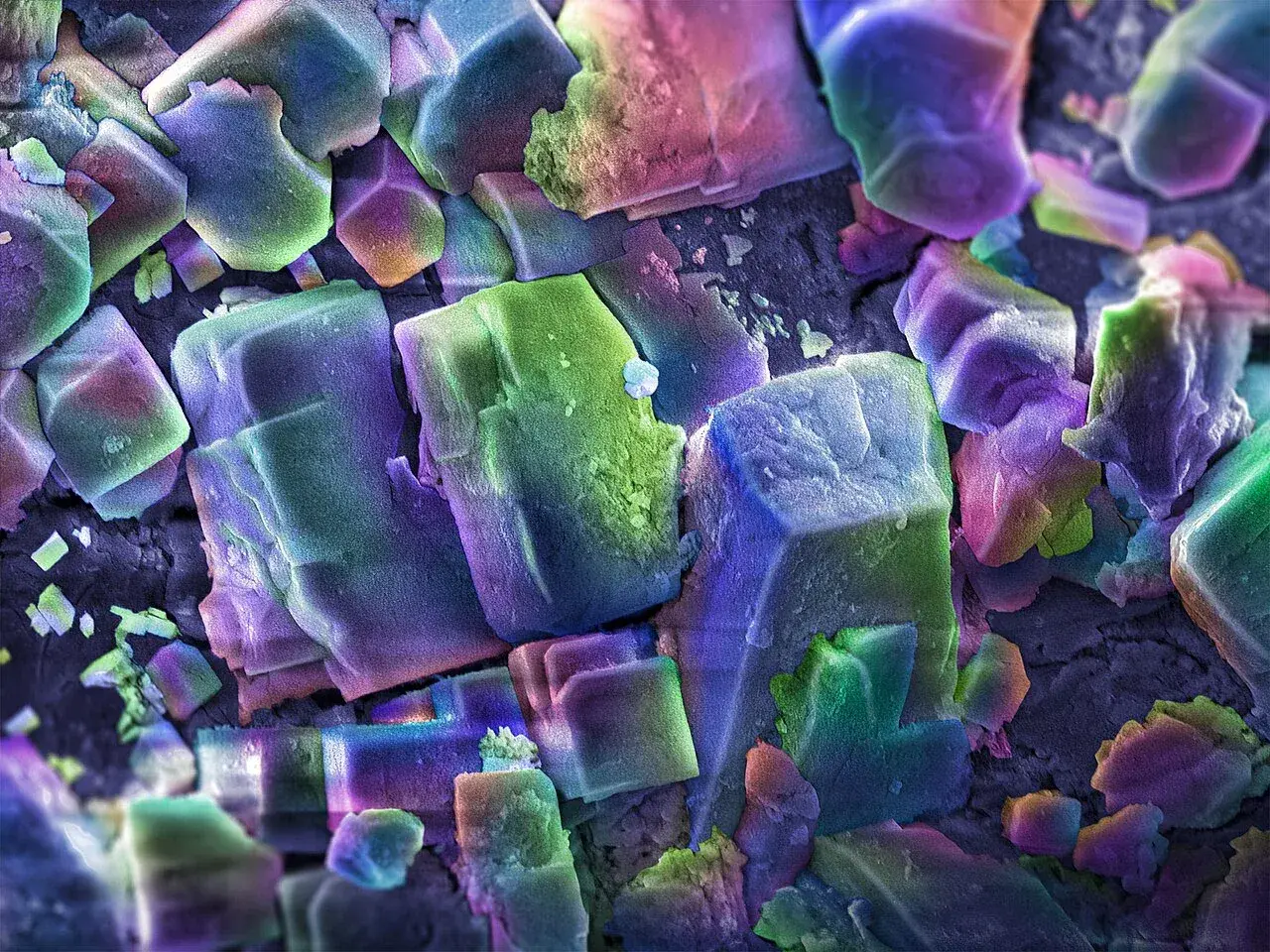

Case Study 1: Gold Nanoparticles

Gold NPs provided a relatively simple test case: an inert metallic core with various surface functionalizations. Key insights: core composition and size are essential, surface chemistry (what molecules are attached) matters critically, shape can dramatically affect properties, and dynamic properties like protein corona formation belong outside the intrinsic NInChI representation. This established the boundary: NInChI should capture intrinsic, stable properties.

Case Study 2: Carbon Nanomaterials

Carbon nanotubes and graphene introduced additional complexity: dimensionality (1D tubes vs 2D sheets vs 0D fullerenes), chirality (the (n,m) vector that defines a nanotube’s structure), defects and impurities that can dramatically alter properties, and layer count for 2D materials. This case showed that the notation needed to handle both topological complexity and chemical composition.

Case Study 3: Complex Engineered Materials

Doped materials, alloys, and core-shell structures revealed key requirements: need to distinguish true alloys (homogeneous mixing) and core-shell structures with the same overall composition, crystal structure information becomes crucial, and component ratios must be precisely specified.

Case Study 4: Database Applications

The FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles guided this analysis. NInChI addresses real database problems: it provides greater specificity than CAS numbers (which lack nanoform distinction), offers a systematic alternative to ad-hoc naming schemes, and enables machine-searchability.

Case Study 5: Computational Modeling

This revealed exciting possibilities: automated descriptor generation from NInChI structure, read-across predictions for untested materials, and model input preparation from standardized notation. The layered structure provides exactly the kind of structured input that computational tools need.

Case Study 6: Regulatory Applications

Under frameworks like REACH, regulators need to distinguish between different “nanoforms”, which are materials with the same chemical composition but different sizes, shapes, or surface treatments. NInChI directly addresses this by encoding the specific properties that define regulatory categories, providing precision sufficient for legal definitions and risk assessment frameworks.

The NInChI Alpha Specification in Practice

Synthesizing insights from all six case studies, the authors propose the NInChI alpha specification, a three-layer structure:

Layer 1 (Version Information): Standard header indicating the NInChI version and specification level, similar to how regular InChI strings start with InChI=1S/.

Layer 2 (Composition): Each component (core, shell, ligands) gets described using standard InChI for chemical composition where possible, morphology sublayers for size and shape information, crystal structure data when relevant, and spatial arrangement details.

Layer 3 (Arrangement): Specifies how all components from Layer 2 fit together, essentially the “assembly instructions” for the nanomaterial, describing the structure from inside-out with core-shell arrangements, surface attachment modes, and hierarchical organization.

The paper provides concrete examples: a 20 nm silica sphere with 2 nm gold shell (simple core-shell structure), a CTAB-capped gold nanoparticle (surface ligand representation), and a chiral single-walled carbon nanotube (topological information encoding). These examples reveal both the power and complexity: the notation can represent sophisticated structures, and the strings get quite detailed. For instance, a basic alpha NInChI representation for a nanoparticle might follow a syntax pattern indicating the core composition and subsequent layers:

InChI=1S/nano/1/Au/2/shp:sph/sz:20nm/3/lig:CTAB

(Note: This is a stylized representation of the alpha syntax to demonstrate the hierarchical layer-based structure.)

Implementation: The authors built a prototype web interface for generating NInChI strings, providing a user-friendly interface, real-time generation, community feedback mechanism, and testing platform.

Limitations: The alpha version acknowledges areas for future development: the scope currently focuses on essential properties, needs broader community testing and refinement, requires implementation in existing nanoinformatics tools, and must undergo formal standardization processes.

Impact: For researchers, NInChI could transform how nanomaterials data gets shared through precise structural queries. For regulators, it provides systematic identification for risk assessment. For industry, standardized notation enables better inventory management, quality control, and automated safety assessment.

Next Steps: Community adoption, software implementation in existing tools, formal standardization through IUPAC or similar bodies, and extension beyond the alpha scope.

Key Conclusions: The work demonstrates that creating systematic notation for nanomaterials is a complex and feasible task. The hierarchical, inside-out organization provides an intuitive approach. Testing against real scenarios identified essential features. By extending InChI, the work leverages existing infrastructure. Success will depend on community adoption and continued refinement based on real-world usage.

Reproducibility Details

- Paper Accessibility: The paper is fully open-access under the CC BY 4.0 license, allowing for straightforward reading and analysis.

- Tools & Code: The authors provided a prototype graphical web interface for generating basic NInChI strings available through the Enalos Cloud Platform. However, the underlying backend code for generating these representations was not released as an open-source library, limiting automated programmatic implementation.

- Documentation: The paper serves as an alpha specification Request for Comments (RFC). As a conceptual framework prototype, no formal algorithmic pseudocode for automated string parsing or generation from structured nanomaterials files (like

.cif) is provided.

Paper Information

Citation: Lynch, I., Afantitis, A., Exner, T., et al. (2020). Can an InChI for Nano Address the Need for a Simplified Representation of Complex Nanomaterials across Experimental and Nanoinformatics Studies? Nanomaterials, 10(12), 2493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10122493

Publication: Nanomaterials (2020)

@article{lynch2020inchi,

title={Can an InChI for Nano Address the Need for a Simplified Representation of Complex Nanomaterials across Experimental and Nanoinformatics Studies?},

author={Lynch, Iseult and Afantitis, Antreas and Exner, Thomas and others},

journal={Nanomaterials},

volume={10},

number={12},

pages={2493},

year={2020},

publisher={MDPI},

doi={10.3390/nano10122493}

}