Contribution and Paper Type

This is a Methodological Paper ($\Psi_{\text{Method}}$). It proposes a novel stochastic algorithm, the Hyperbolic Algorithm (HA), and validates its superior efficiency against the existing Langevin Algorithm (LA) through formal error analysis and numerical simulation. It contains significant theoretical derivation (Liouville dynamics) that serves primarily to justify the algorithmic performance claims.

Motivation and Gaps in Prior Work

The standard Langevin Algorithm (LA) for numerical simulation of Euclidean field theories suffers from efficiency bottlenecks. The simplest Euler-discretization of the LA introduces systematic errors of $O(\epsilon)$ (where $\epsilon$ is the step size). To maintain accuracy, $\epsilon$ must be kept small, which increases the sweep-sweep correlation time (autocorrelation time), making simulations computationally expensive.

Core Novelty: Second-Order Dynamics

The core contribution is the introduction of a second-order derivative in fictitious time to the stochastic equation. This converts the parabolic Langevin equation into a hyperbolic equation:

$$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial^{2}\phi}{\partial t^{2}}+\gamma\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t}=-\frac{\partial S}{\partial\phi}+\eta \end{aligned} $$

Equation Comparison

The key difference from the standard (first-order) Langevin equation:

| Equation Type | Formula |

|---|---|

| Hyperbolic (Second Order) | $$\frac{\partial^{2}\phi}{\partial t^{2}}+\gamma\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t}=-\frac{\partial S}{\partial\phi}+\eta$$ |

| Langevin (First Order) | $$\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial t}=-\frac{\partial S}{\partial\phi}+\eta$$ |

The standard Langevin equation corresponds to the overdamped limit where the acceleration term is absent. Physically, the Hyperbolic equation can be viewed as microcanonical equations of motion with an added friction term.

Key Innovations

- Higher Order Accuracy: The simplest discretization of this equation leads to systematic errors of only $O(\epsilon^2)$ compared to $O(\epsilon)$ for LA.

- Tunable Damping: The addition of the damping parameter $\gamma$ allows tuning to minimize autocorrelation tails.

- Uniform Evolution: The method evolves structures of different wavelengths more uniformly than LA due to the specific dissipation structure.

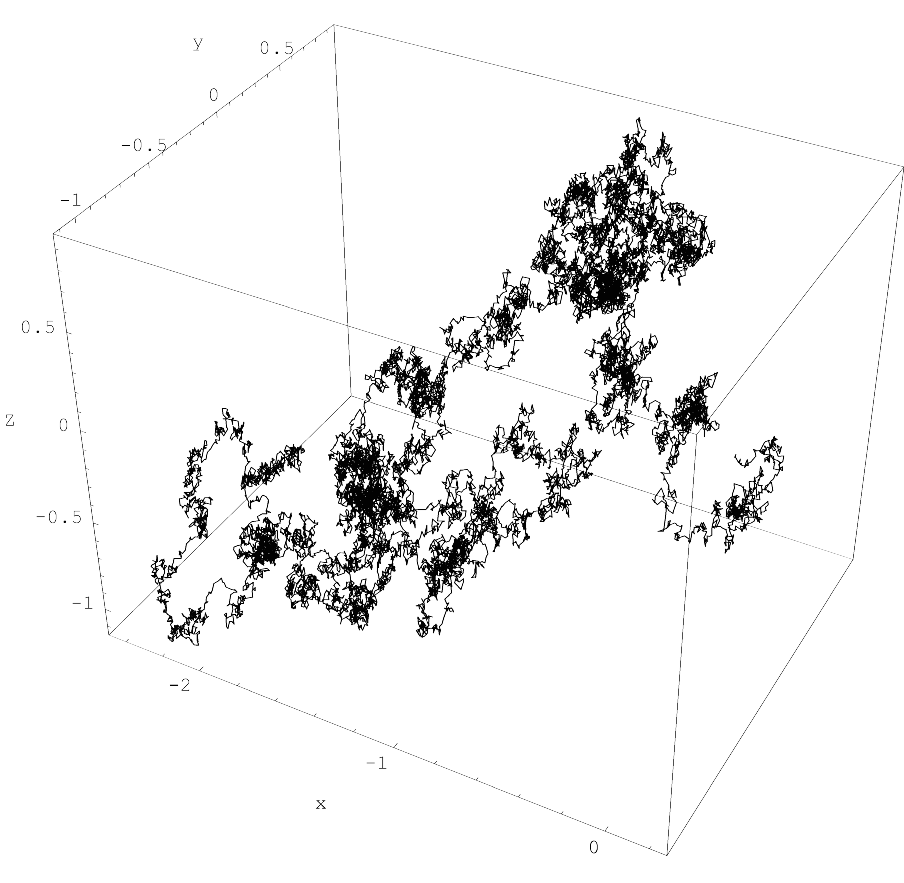

Methodology and Experiments

The author validated the method using the XY Model on 2D lattices.

- System: Euclidean action $S = -\sum_{x,\mu} \cos(\theta_{x+\mu} - \theta_x)$.

- Setup:

- Lattice sizes: $15^2$ (helical boundary conditions) and $30^2$.

- $\beta$ range: 0.9 to 1.2 (crossing the critical point $\approx 1.0$).

- Run length: >100,000 updates in equilibrium.

- Metrics:

- Autocorrelation time ($\tau$): Defined as the number of updates for the time-correlation function to drop to 10% of its initial value.

- Systematic Error: Measured via deviation of average action from Monte Carlo values.

Results and Conclusions

- Efficiency: The Hyperbolic Algorithm (HA) is far more efficient. For equal systematic errors, sweep-sweep correlation times are significantly lower than LA.

- Error Scaling: Numerical results confirmed that HA step size $\epsilon_H = 0.1$ yields systematic errors comparable to LA step size $\epsilon_L \approx 0.008$ ($O(\epsilon^2)$ vs $O(\epsilon)$ scaling).

- Speedup: In the disordered phase, HA is roughly $\epsilon_H / \epsilon_L$ times faster (approximately a factor of 25). In the ordered phase, efficiency gains increase with distance scale, reaching factors >20 for long-range correlations.

- Optimal Damping: For the XY model, the optimal damping parameter was found to be $\gamma \approx 0.4$.

Reproducibility Details

Algorithms

1. The Hyperbolic Algorithm (HA)

The discretized update equations for scalar fields are:

$$ \begin{aligned} \pi_{t+\epsilon} - \pi_{t} &= -\epsilon\gamma\pi_{t} - \epsilon\frac{\partial S}{\partial\phi_{t}} + \sqrt{2\epsilon\gamma/\beta}\xi_{t} \\ \phi_{t+\epsilon} - \phi_{t} &= \epsilon\pi_{t+\epsilon} \end{aligned} $$

- Variables: $\phi$ is the field, $\pi$ is the conjugate momentum ($\dot{\phi}$).

- Parameters: $\epsilon$ (step size), $\gamma$ (damping constant).

- Noise: $\xi$ is Gaussian noise with $\langle\xi_x \xi_y\rangle = \delta_{x,y}$.

- Storage: Requires storing both $\phi$ and $\pi$ vectors.

2. Non-Abelian Generalization

For Lie group elements $U$ with generators $T^a$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \pi_{t+\epsilon}^a - \pi_{t}^a &= -\epsilon\gamma\pi_{t}^a - \epsilon\delta^a S[U_t] + \sqrt{2\epsilon\gamma/\beta}\xi_{t}^a \\ U_{t+\epsilon} &= e^{i\epsilon\pi_{t+\epsilon}^a T^a} U_t \end{aligned} $$

Theoretical Proof of $O(\epsilon^2)$ Accuracy

The derivation relies on the generalized Liouville equation for the probability distribution $P[\phi, \pi; t]$.

- Transition Probability: The transition $W$ for one iteration is defined.

- Effective Liouville Operator: The evolution is written as $P(t+\epsilon) = \exp(\epsilon L_{\text{eff}}) P(t)$.

- Baker-Hausdorff Expansion: Using normal ordering of operators, the equilibrium distribution $P_{\text{eq}}$ is derived through $O(\epsilon^2)$:

$$ \begin{aligned} P_{\text{eq}} &= \exp\left\lbrace-\frac{1}{2}\beta_{1}\sum_{x}\pi_{x}^{2} - \beta S[\phi] + \frac{1}{2}\epsilon\beta\sum_{x}\pi_{x}S_{x} + \epsilon^{2}G + O(\epsilon^3)\right\rbrace \end{aligned} $$

where $\beta_1 = \beta\left(1 - \frac{1}{2}\epsilon\gamma\right)$.

- Effective Action: Integrating out $\pi$ yields the effective action for $\phi$:

$$ \begin{aligned} S_{\text{eff}}[\phi] &= S[\phi] - \frac{1}{8}\epsilon^2 \sum_x S_x^2 + \dots \end{aligned} $$

The absence of $O(\epsilon)$ terms proves the higher-order accuracy.

Evaluation

- Model: XY Model (2D)

- Hamiltonian: $H = \frac{1}{2}\sum \pi^2 + S[\phi]$ where $S = -\sum \cos(\Delta \theta)$.

- Observables:

- $\Gamma_n = \cos(\theta_{m+n} - \theta_m)$ (averaged over lattice $m$).

- Comparisons:

- LA Step: $\epsilon_L \approx 0.005 - 0.02$.

- HA Step: $\epsilon_H \approx 0.1 - 0.2$.

- Equivalence: $\epsilon_H = 0.1$ matches error of $\epsilon_L \approx 0.008$.

Terminology Note

The naming conventions in this paper differ from those commonly used in molecular dynamics (MD). The following table provides a cross-field mapping:

| Concept | Field Theory (This Paper) | Molecular Dynamics | Mathematics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equation 1 | “Langevin Equation” | Brownian Dynamics (BD) | Overdamped Langevin |

| Equation 2 | “Hyperbolic Equation” | Langevin Dynamics (LD) | Underdamped Langevin |

| Integrator 1 | Euler Discretization | Euler Integrator | Euler-Maruyama |

| Integrator 2 | Hyperbolic Algorithm (HA) | Velocity Verlet / Leapfrog | Quasi-Symplectic Splitting |

Key insight: The paper’s “Hyperbolic Algorithm” is mathematically equivalent to Langevin Dynamics with a Leapfrog/Verlet integrator, commonly used in MD. The baseline “Langevin Algorithm” corresponds to Brownian Dynamics. The term “Langevin equation” is overloaded: field theorists often use it for overdamped dynamics (no inertia), while chemists assume it includes momentum ($F=ma$).

Paper Information

Citation: Horowitz, A. M. (1987). The Second Order Langevin Equation and Numerical Simulations. Nuclear Physics B, 280, 510-522. https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(87)90159-3

Publication: Nuclear Physics B 1987

@article{horowitzSecondOrderLangevin1987,

title = {The Second Order {{Langevin}} Equation and Numerical Simulations},

author = {Horowitz, Alan M.},

year = 1987,

month = jan,

journal = {Nuclear Physics B},

volume = {280},

pages = {510--522},

issn = {05503213},

doi = {10.1016/0550-3213(87)90159-3}

}