Contribution: Systematizing the Embedded-Atom Method

This is a Systematization paper (specifically a handbook chapter) with a strong secondary Method projection.

Its primary goal is to serve as a “users’ guide” to the Embedded-Atom Method (EAM). The text organizes existing knowledge:

- It traces the physical origins of EAM from Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Effective Medium Theory.

- It synthesizes “closely related methods” (Second Moment Approximation, Glue Model), showing they are mathematically equivalent or very similar to EAM.

- It provides a pedagogical, step-by-step methodology for fitting potentials to experimental data.

Motivation: Bridging the Gap Between DFT and Pair Potentials

The primary motivation is to bridge the gap between accurate, expensive electronic structure calculations and fast, inaccurate pair potentials.

- Computational Efficiency: First-principles methods scale as $O(N^3)$ or worse, limiting simulations to $<100$ atoms (in 1994). Pair potentials scale as $O(N)$ and fail to capture essential many-body physics of metals.

- Physical Accuracy: Simple pair potentials cannot accurately model metallic defects; they predict zero Cauchy pressure ($C_{12} - C_{44} = 0$) and equate vacancy formation energy to cohesive energy, both of which are incorrect for transition metals.

- Practical Utility: There was a need for a clear guide on how to construct and apply these potentials for large-scale simulations ($10^6+$ atoms) of fracture and defects.

Novelty: A Unified Framework and Robust Fitting Recipe

As a review chapter, the novelty lies in the synthesis and the specific, reproducible recipe for potential construction. Central to this synthesis is the core EAM energy functional:

$$E_{\text{tot}} = \sum_i \left( F(\bar{\rho}_i) + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j \neq i} \phi(r_{ij}) \right)$$

where the total energy $E_{\text{tot}}$ depends on embedding an atom $i$ into a local background electron density $\bar{\rho}_i = \sum_{j \neq i} \rho(r_{ij})$, plus a repulsive pair interaction $\phi(r_{ij})$.

- Unified Framework: It explicitly maps the “Second Moment Approximation” (Tight Binding) and the “Glue Model” onto the fundamental EAM framework above, clarifying that they differ primarily in terminology or specific functional choices (e.g., square root embedding functions).

- Cross-Potential Fitting Recipe: It details a robust method for fitting alloy potentials (specifically Ni-Al-B) by using “transformation invariance”, scaling the density and shifting the embedding function to fit alloy properties without disturbing pure element fits.

- Specific Parameters: It publishes optimized potential parameters for Ni, Al, and B that accurately reproduce properties like the Boron interstitial preference in $\text{Ni}_3\text{Al}$.

Validation: Computational Benchmarks and Simulations

The “experiments” described are computational validations and simulations using the fitted Ni-Al-B potential:

Potential Fitting:

- Pure elements (Ni, Al) were fitted to elastic constants, vacancy formation energies, and diatomic data.

- Boron was fitted using hypothetical crystal structures (fcc, bcc) calculated via LMTO (Linear Muffin-Tin Orbital) since experimental data for fcc B does not exist.

Molecular Statics (Validation):

- Surface Relaxation: Demonstrated that EAM captures the oscillatory relaxation of atomic layers near a free surface, a many-body effect that pair potentials fail to capture.

- Defect Energetics: Calculated formation energies for Boron interstitials in $\text{Ni}_3\text{Al}$. Found the 6Ni-octahedral site is most stable (4.59 eV), consistent with channeling experiments.

Molecular Dynamics (Application):

- Grain Boundary (GB) Cleavage: Simulated the fracture of a (210) tilt grain boundary in $\text{Ni}_3\text{Al}$ at a strain rate of $5 \times 10^{10}$ s$^{-1}$.

- Comparison: Compared pure $\text{Ni}_3\text{Al}$ boundaries vs. those doped with Boron and substitutional Nickel.

Key Outcomes: EAM Efficiency and Boron Strengthening

- EAM Efficiency: Confirmed that EAM scales linearly with atom count ($N$), requiring only 2-5 times the computational work of pair potentials.

- Boron Strengthening Mechanism: The simulations suggested that Boron segregates to grain boundaries and, specifically when co-segregated with Ni, significantly increases cohesion.

- The B-doped boundary required approximately 44% more work to cleave than the undoped boundary.

- The fracture mode shifted from cleaning the GB to failure in the bulk.

- Limitations: The author concludes that while EAM is excellent for metals, it lacks the angular dependence required for strongly covalent materials (like $\text{MoSi}_2$) or directional bonding.

Reproducibility Details

The chapter provides nearly all details required to implement the described potential from scratch.

Data

- Experimental/Reference Data: Used for fitting the cost function $\chi_{\text{rms}}$.

- Pure Elements: Lattice constants ($a_0$), cohesive energy ($E_{\text{coh}}$), bulk modulus ($B$), elastic constants ($C_{11}, C_{12}, C_{44}$), vacancy formation energy ($E_{\text{vac}}^f$), and diatomic bond length/strength ($R_e, D_e$).

- Alloys: Heat of solution and defect energies (APB, SISF) for $\text{Ni}_3\text{Al}$.

- Hypothetical Data: LMTO first-principles data used for unobserved phases (e.g., fcc Boron, B2 NiB) to constrain the fit.

Algorithms

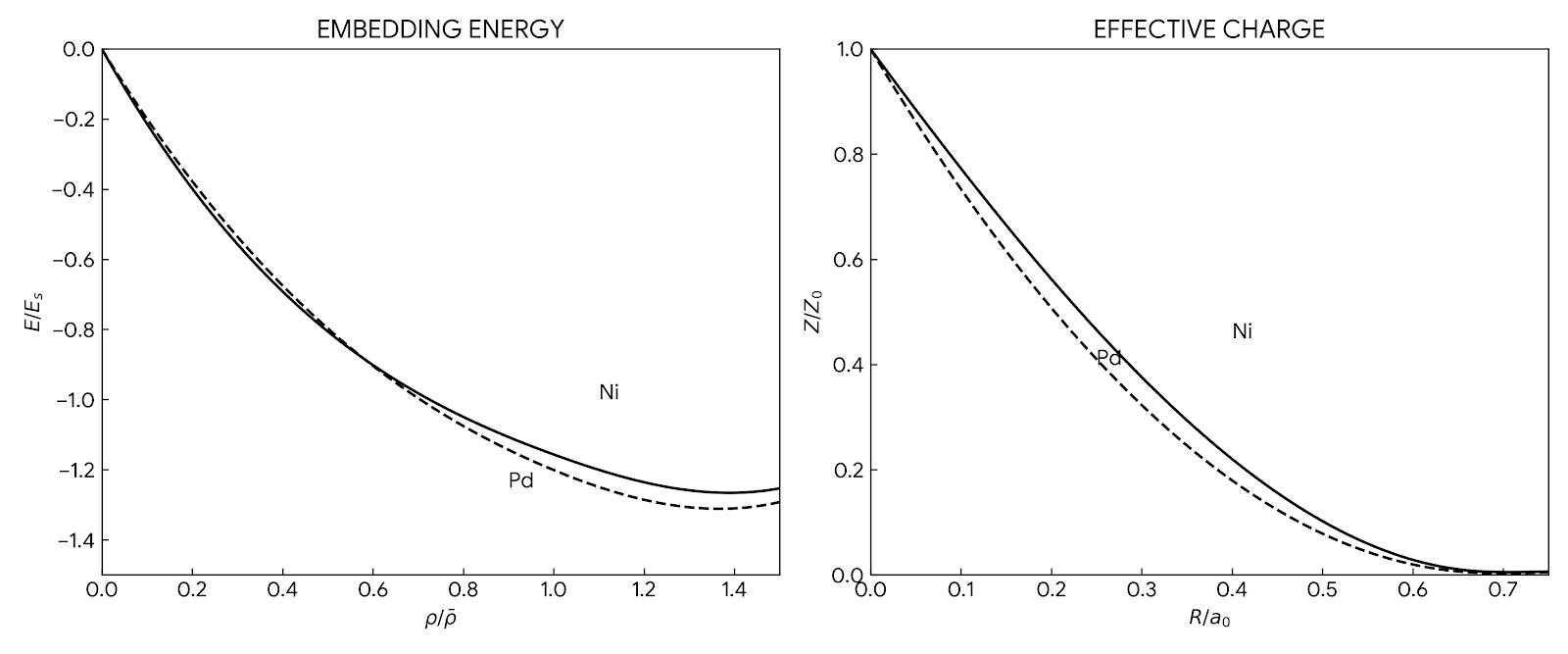

- Component Functions:

- Pair Potential $\phi(r)$: Morse potential form: $$\phi(r) = D_M {1 - \exp[-\alpha_M(r - R_M)]}^2 - D_M$$

- Density Function $\rho(r)$: Modified hydrogenic 4s orbital: $$\rho(r) = r^6(e^{-\beta r} + 2^9 e^{-2\beta r})$$

- Embedding Function $F(\bar{\rho})$: Derived numerically to force the crystal energy to match the “Universal Energy Relation” (Rose et al.) as a function of lattice constant.

- Fitting Strategy:

- Smooth Cutoff: A polynomial smoothing function ($h_{\text{smooth}}$) applied at $r_{\text{cut}}$ to ensure continuous derivatives.

- Simplex Algorithm: Used to optimize parameters ($D_M, R_M, \alpha_M, \beta, r_{\text{cut}}$).

- Alloy Invariance: Used transformations $F’(\rho) = F(\rho) + g\rho$ and $\rho’(r) = s\rho(r)$ to fit cross-potentials without altering pure-element properties.

Models

- Parameters: The text provides the exact optimized parameters for the Ni-Al-B potential in Table 2 (Pure elements) and Table 5 (Cross-potentials).

- Example Ni parameters: $D_M=1.5335$ eV, $\alpha_M=1.7728$ Å$^{-1}$, $r_{\text{cut}}=4.7895$ Å.

Hardware

- 1994 Context: Mentions that simulations of $10^6$ atoms were possible on the “fastest computers available”.

- Scaling: Explicitly notes computational work scales as $O(N)$, roughly 2-5x slower than pair potentials.

Paper Information

Citation: Voter, A. F. (1994). Chapter 4: The Embedded-Atom Method. In Intermetallic Compounds: Vol. 1, Principles, edited by J. H. Westbrook and R. L. Fleischer. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Publication: Intermetallic Compounds: Vol. 1, Principles (1994)

@incollection{voterEmbeddedAtomMethod1994,

title = {The Embedded-Atom Method},

author = {Voter, Arthur F.},

booktitle = {Intermetallic Compounds: Vol. 1, Principles},

editor = {Westbrook, J. H. and Fleischer, R. L.},

year = {1994},

publisher = {John Wiley & Sons Ltd},

pages = {77--90},

chapter = {4}

}

Additional Resources:

- NIST Interatomic Potentials Repository (Modern repository often hosting EAM files)

- Original EAM Paper (1984)

- EAM Review (1993)