Paper Information

Citation: Daw, M. S., & Baskes, M. I. (1984). Embedded-atom method: Derivation and application to impurities, surfaces, and other defects in metals. Physical Review B, 29(12), 6443-6453. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.29.6443

Publication: Physical Review B, 1984

Additional Resources:

What kind of paper is this?

This is a foundational method paper that introduces a new class of semi-empirical, many-body interatomic potential: the Embedded-Atom Method (EAM). It is designed for large-scale atomistic simulations of metallic systems, bridging the gap between computationally cheap (but physically limited) pair potentials and accurate (but expensive) quantum mechanical methods. The EAM achieves pair-potential speed while incorporating many-body physics inspired by density functional theory.

What is the motivation?

The authors sought to overcome the limitations of pair potentials (the dominant method of the time), which failed in three key areas:

- Elastic Anisotropy: Pair potentials enforce the Cauchy relation ($C_{12} = C_{44}$), which is violated by most transition metals.

- Volume Ambiguity: Pair potentials require a volume-dependent energy term, making them impossible to use accurately on surfaces or cracks where local volume is undefined.

- Chemical Incompatibility: Pair potentials cannot model chemically active impurities like Hydrogen.

First-principles quantum mechanical methods (e.g., band theory) are accurate but computationally intractable for the large systems (thousands of atoms) needed to study defects, surfaces, and mechanical properties.

The goal was to create a new model that bridges this gap in accuracy and computational cost.

What is the novelty here?

The EAM postulates that the energy of an atom is determined by the local electron density of its neighbors. The total energy is:

$$E_{tot} = \sum_{i} F_i(\rho_{h,i}) + \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i \neq j} \phi_{ij}(R_{ij})$$

- $F_i(\rho_{h,i})$ (Embedding Energy): The energy required to embed atom $i$ into the background electron density $\rho$ provided by its neighbors. This term is non-linear and captures many-body effects.

- $\phi_{ij}$ (Pair Potential): A short-range electrostatic repulsion between cores.

- $\rho_{h,i}$ (Host Density): Approximated as a linear superposition of atomic densities: $\rho_{h,i} = \sum_{j \neq i} \rho^a_j(R_{ij})$.

The key innovations are:

- The Embedding Energy: Each atom $i$ contributes an energy $F_i$ which is a non-linear function of the local electron density $\rho_{h,i}$ it is embedded in. This density is approximated as a simple linear superposition of the atomic electron densities of all its neighbors. This term captures the crucial many-body effects of metallic bonding.

- A Redefined Pair Potential: A short-range, two-body potential $\phi_{ij}$ is retained, but it primarily models the electrostatic core-core repulsion.

- Elimination of the “Volume” Problem: Because the embedding energy depends on the local electron density (a quantity that is always well-defined, even at a surface or a crack tip), the method elegantly circumvents the ambiguities of volume-dependent pair potentials.

- Intrinsic Many-Body Nature: The non-linearity of the embedding function $F(\rho)$ naturally accounts for why chemically active impurities (like hydrogen) cannot be described by pair potentials and correctly breaks the Cauchy relation for elastic constants.

What experiments were performed?

The authors validated EAM through a rigorous split between parameterization data and prediction tasks:

Fitting Data (Bulk Properties Only):

The model parameters were fitted exclusively to these experimental values for Ni and Pd:

- Lattice constant ($a_0$)

- Elastic constants ($C_{11}, C_{12}, C_{44}$)

- Sublimation energy ($E_s$)

- Vacancy-formation energy ($E_{1V}^F$)

- Hydrogen heat of solution (for fitting H parameters)

Validation Tests (No Further Fitting):

The model was then evaluated on its ability to predict these properties without any additional parameter adjustments:

- Surface Relaxations: Ni(110) surface contraction

- Surface Energy: Ni(100) surface energy

- Hydrogen Migration: H migration energy in Pd

- Fracture Mechanics: Hydrogen embrittlement in Ni slabs

What outcomes/conclusions?

- Many-Body Physics: The embedding function $F(\rho)$ successfully captures the volume-dependence of metallic cohesion, fixing the “Cauchy discrepancy” inherent in pair potentials.

- Predictive Power: A single set of functions, fitted only to bulk data, successfully generalized to surfaces (Ni(110) contraction: -0.11 Å vs. experiment; Ni(100) surface energy: 1550 vs. 1725 erg/cm² experimental average), vacancies, and hydrogen migration (0.26 eV in Pd, matching experiment exactly).

- Efficiency and Scope: The method is computationally practical for large-scale simulations of defects and fractures, successfully treating chemically active impurities (H) where pair potentials fundamentally fail.

Reproducibility Details

Algorithms

To replicate the method, three specific algorithmic definitions are needed:

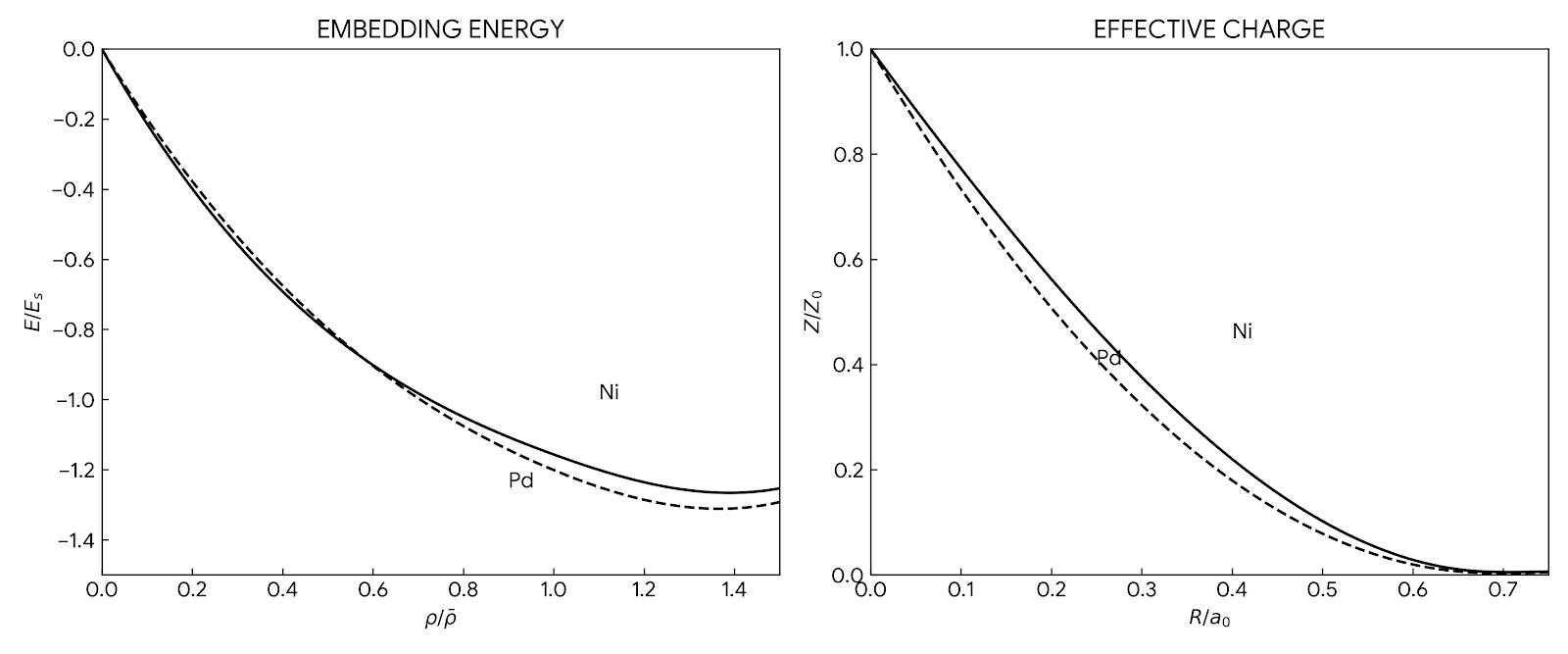

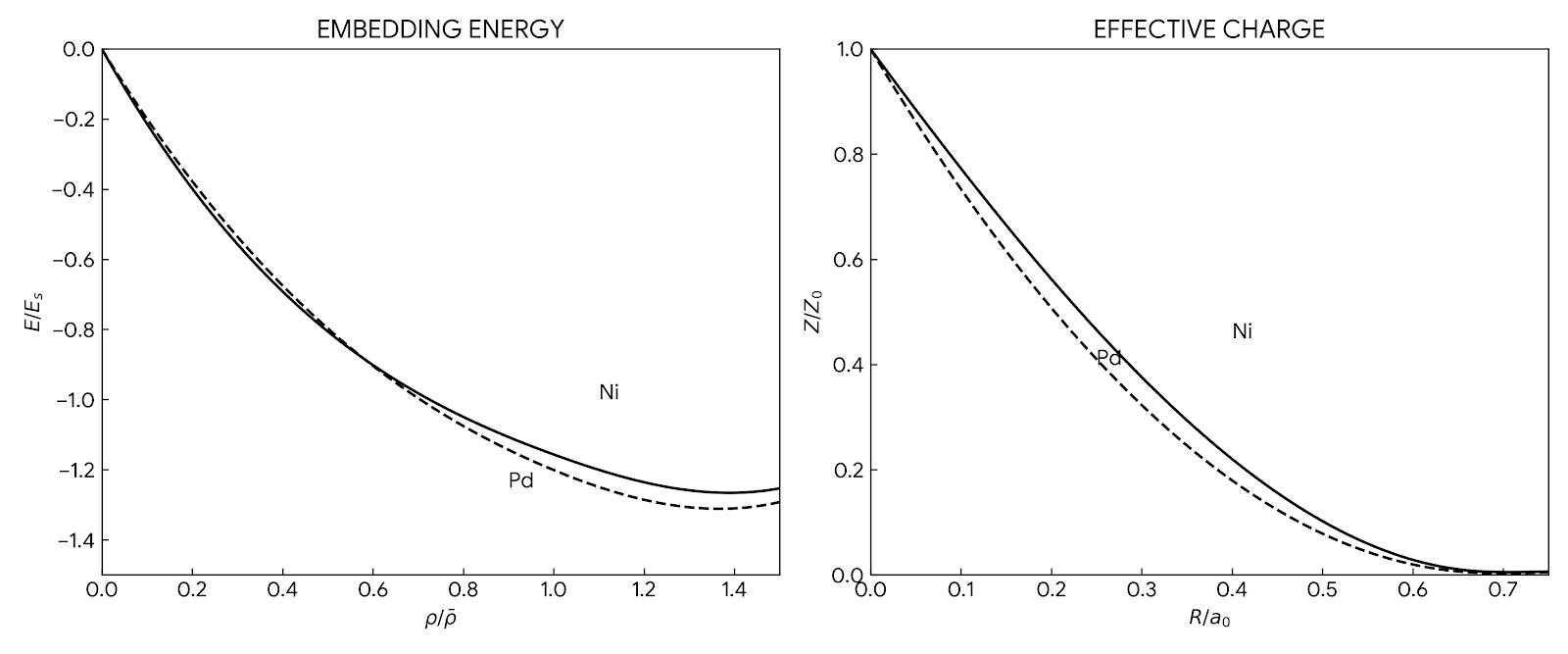

Atomic Density Construction: The electron density $\rho^a(r)$ is a weighted sum of Hartree-Fock $s$ and $d$ orbital densities (from Clementi & Roetti tables), controlled by a parameter $N_s$ (the number of s-like electrons): $$\rho^a(r) = N_s\rho_s^a(r) + (N-N_s)\rho_d^a(r)$$ For Ni, $N_s = 0.85$; for Pd, $N_s = 0.65$ (fitted to H solution heat).

Pair Potential Form: The pair potential is defined via an effective charge function $Z(r)$, not directly as a potential: $$\phi_{ij}(r) = \frac{Z_i(r)Z_j(r)}{r}$$ Splines for $Z(r)$ are provided in Table II.

Analytic Forces: Because embedding energy depends on neighbor density, the force calculation is many-body: $$\vec{f}_{k} = -\sum_{j(\neq k)} (F’_{k} \rho’_{j} + F’_{j} \rho’_{k} + \phi’_{jk}) \vec{r}_{jk}$$

Models

The functions $F(\rho)$ and $\phi(r)$ are modeled using cubic splines, with parameters fitted to reproduce bulk experimental constants. The embedding function $F(\rho)$ is constrained to have a single minimum and to be linear at high densities (preventing unphysical behavior under extreme compression). Energy minimization uses the conjugate gradients technique. The paper explicitly lists spline knots, coefficients, and cutoffs in Tables II and IV, making the method fully reproducible.

Evaluation

Fitting Data (Used for Parameterization):

Bulk experimental properties for Ni and Pd only:

- Lattice constant ($a_0$)

- Elastic constants ($C_{11}, C_{12}, C_{44}$)

- Sublimation energy ($E_s$)

- Vacancy-formation energy ($E_{1V}^F$)

- Hydrogen heat of solution (for fitting H parameters)

Validation Results (Predictions Without Further Fitting):

| Property | Predicted | Experimental | Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni(110) surface contraction | -0.11 Å | - | Qualitative |

| Ni(100) surface energy | 1550 erg/cm² | 1725 erg/cm² | Close |

| H migration in Pd | 0.26 eV | 0.26 eV | Exact |

| H embrittlement in Ni | Qualitative model | - | Qualitative |