Paper Information

Citation: Lennard-Jones, J. E. (1932). Processes of Adsorption and Diffusion on Solid Surfaces. Transactions of the Faraday Society, 28, 333-359. https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9322800333

Publication: Transactions of the Faraday Society, 1932

What kind of paper is this?

This is a foundational theoretical paper. It derives physical laws for adsorption potentials (Section 2) and diffusion kinetics (Section 4) from first principles, validating them against external experimental data (Ward, Benton). It bridges electronic structure theory (potential curves) and statistical mechanics (diffusion rates). It is not an experimental or computational paper in the modern sense but rather a work that provides a unifying theoretical framework to explain a range of experimental observations.

What is the motivation?

The primary motivation was to reconcile conflicting experimental evidence regarding the nature of gas-solid interactions. At the time, it was observed that the same gas and solid could interact weakly at low temperatures (consistent with van der Waals forces) but exhibit strong, chemical-like bonding at higher temperatures, a process requiring significant activation energy. The paper seeks to provide a single, coherent model that can explain both “physical adsorption” (physisorption) and “activated” or “chemical adsorption” (chemisorption) and the transition between them.

What is the novelty here?

The core novelty is the application of quantum mechanical potential energy surfaces to the problem of surface adsorption. The key conceptual breakthroughs are:

Dual Potential Energy Curves: The paper proposes that the state of the system must be described by at least two distinct potential energy curves as a function of the distance from the surface:

- One curve represents the interaction of the intact molecule with the surface (e.g., H₂ with a metal). This corresponds to weak, long-range van der Waals forces.

- A second curve represents the interaction of the dissociated constituent atoms with the surface (e.g., 2H atoms with the metal). This corresponds to strong, short-range chemical bonds.

Activated Adsorption via Curve Crossing: The transition from the molecular (physisorbed) state to the atomic (chemisorbed) state occurs at the intersection of these two potential energy curves. For a molecule to dissociate and chemisorb, it must possess sufficient energy to reach this crossing point. This energy is identified as the energy of activation, which had been observed experimentally.

Unified Model: This model elegantly unifies physisorption and chemisorption into a single continuous process. A molecule approaching the surface is first trapped in the shallow potential well of the physisorption curve. If it acquires enough thermal energy to overcome the activation barrier, it can transition to the much deeper potential well of the chemisorption state. This provides a clear physical picture for temperature-dependent adsorption phenomena.

What experiments were performed?

This is a theoretical paper with no original experiments performed by the author. However, Lennard-Jones validates his theoretical framework against existing experimental data from other researchers:

- Ward’s data: Hydrogen absorption on Copper - used to validate the square root time law for slow sorption kinetics

- Benton’s observations: Referenced for activated adsorption phenomena

- van der Waals constant data: Used existing measurements of diamagnetic susceptibility to calculate predicted heats of adsorption (e.g., Argon on Copper yielding approximately 6000 calories)

The validation approach involves deriving theoretical predictions from first principles and showing they match the functional form and magnitude of independently measured experimental results.

What outcomes/conclusions?

Key Outcomes:

- The paper introduced the now-famous Lennard-Jones diagram for surface interactions, plotting potential energy versus distance from the surface for both molecular and dissociated atomic species. This graphical model became a cornerstone of surface science.

- Derived the square root time law ($S \propto \sqrt{t}$) for slow sorption kinetics, validated against Ward’s experimental data.

- Established quantitative connection between adsorption potentials and measurable atomic properties (diamagnetic susceptibility).

Conclusions:

- The nature of adsorption is determined by the interplay between two distinct potential states (molecular and atomic).

- “Activated adsorption” is the process of overcoming an energy barrier to transition from a physically adsorbed molecular state to a chemically adsorbed atomic state.

- The model predicts that the specific geometry of the surface (i.e., the lattice spacing) and the orientation of the approaching molecule are critical, as they influence the shape of the potential energy surfaces and thus the magnitude of the activation energy.

- The reverse process (recombination of atoms and desorption of a molecule) also requires activation energy to move from the chemisorbed state back to the molecular state.

- This entire mechanism is proposed as a fundamental factor in heterogeneous catalysis, where the surface acts to lower the activation energy for molecular dissociation, facilitating chemical reactions.

Mathematical Derivations

Van der Waals Calculation (Section 2)

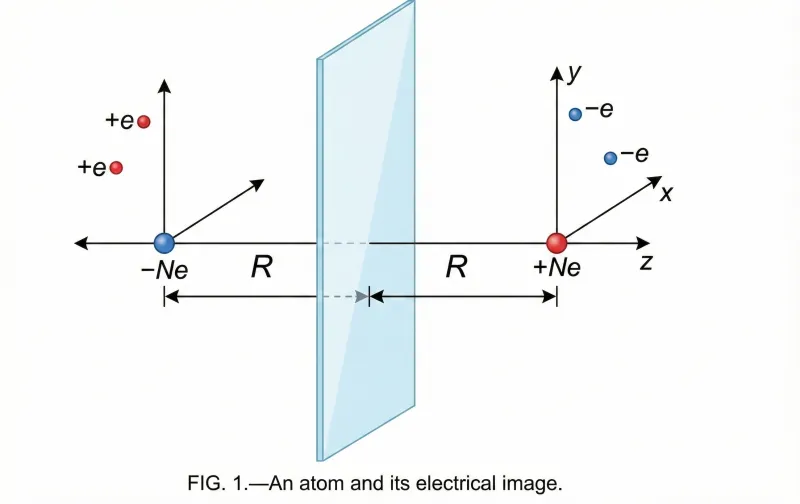

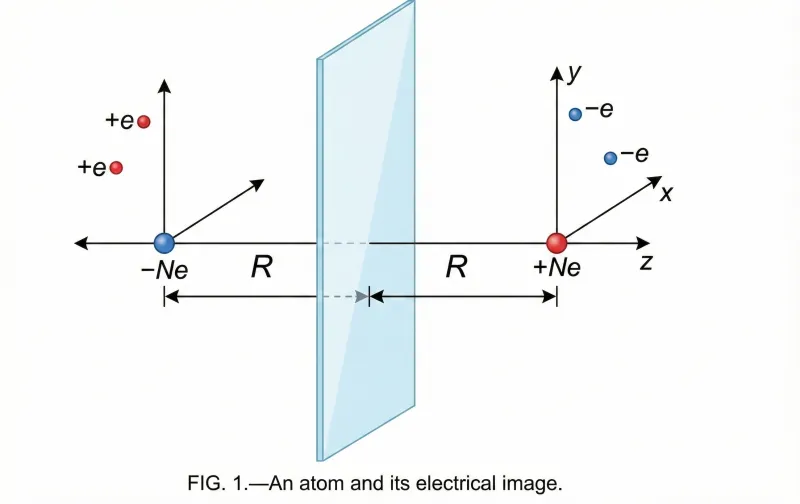

The paper derives the attractive force between a neutral atom and a metal surface using Maxwellian electrical images. The key steps are:

- Method of Images: Lennard-Jones models the metal as a perfect electrical conductor. When a neutral atom approaches, its instantaneous dipole moment induces image charges in the metal surface.

- The Interaction Potential: The resulting potential energy $W$ of an atom at distance $R$ from the metal surface is:

$$W = -\frac{e^2 \overline{r^2}}{6R^3}$$

where $\overline{r^2}$ is the mean square distance of electrons from the nucleus.

- Connection to Measurable Properties: This theoretical potential can be calculated using diamagnetic susceptibility ($\chi$). The interaction simplifies to:

$$W = \mu R^{-3}$$

where $\mu = mc^2\chi/L$ connects the adsorption potential to measurable magnetic properties of the atom.

- Repulsive Forces and Equilibrium: By assuming repulsive forces account for approximately 40% of the potential at equilibrium, Lennard-Jones estimates heats of adsorption. For Argon on Copper, this yields approximately 6000 calories.

Kinetic Theory of Slow Sorption (Section 4)

The paper extends beyond surface phenomena to model how gas enters the bulk solid (absorption). This section is critical for understanding time-dependent adsorption kinetics.

The “Cracks” Hypothesis

Lennard-Jones proposes that “slow sorption” is lateral diffusion along “smekal cracks” (fissures or defects) in the solid surface. This explains why sorption rates differ from predictions based on bulk diffusion coefficients.

The Diffusion Equation

The problem is formulated using Fick’s second law:

$$\frac{\partial n}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^{2}n}{\partial x^{2}}$$

where $n$ is the concentration of adsorbed atoms, $t$ is time, $D$ is the diffusion coefficient, and $x$ is the position along the crack.

Derivation of the Diffusion Coefficient

The diffusion coefficient is derived from kinetic theory:

$$D = \frac{\bar{c}^2 \tau^2}{2\tau^*}$$

where:

- $\bar{c}$ is the mean velocity of mobile atoms

- $\tau$ is the time an atom spends in the mobile (activated) state

- $\tau^*$ is the interval between activation events

Atoms are “activated” to a mobile state with energy $E_0$, after which they can migrate along the surface.

The Square Root Law

Solving the diffusion equation for a semi-infinite crack yields the total amount of gas absorbed $S$ as a function of time:

$$S = 2n_0 \sqrt{\frac{Dt}{\pi}}$$

This predicts that absorption scales with the square root of time:

$$S \propto \sqrt{t}$$

Experimental Validation

Lennard-Jones validates this derivation by re-analyzing Ward’s experimental data on the Copper/Hydrogen system. Plotting the absorbed quantity against $\sqrt{t}$ produces linear curves, confirming the theoretical prediction.

Surface Topography and 3D Contours

The notes above imply a one-dimensional process (distance from surface). The paper explicitly expands this to three dimensions to explain surface migration.

Potential “Tunnels”

Lennard-Jones models the surface potential as 3D contour surfaces resembling “underground caverns” or tunnels. The potential energy landscape above a crystalline surface has periodic minima and saddle points.

Surface Migration

Atoms migrate along “tunnels” of low potential energy between surface atoms. The activation energy for surface diffusion corresponds to the barrier height between adjacent potential wells on the surface. This geometric picture explains:

- Why certain crystallographic orientations are more reactive

- The temperature dependence of surface diffusion rates

- The role of surface defects in catalysis