Paper Summary

Citation: Levinthal, C. (1969). How to Fold Graciously. In Mössbauer Spectroscopy in Biological Systems: Proceedings of a meeting held at Allerton House, Monticello, Illinois (pp. 22-24). University of Illinois Press.

Publication: Mössbauer Spectroscopy in Biological Systems Proceedings, 1969

External Links:

- Full Paper (PDF): Georgia Tech Biosimulation Course

- Levinthal’s Paradox (Wikipedia)

1. Taxonomy Classification

This paper functions differently than a standard experimental or methods paper:

- Primary Basis: Perspective. This paper defines a “Grand Challenge” and argues for a conceptual shift in how we view biomolecular assembly.

- Secondary Basis: Theory. It uses formal combinatorial arguments to establish the bounds of the search space ($10^{300}$ configurations).

- Tertiary Basis: Discovery. It uses experimental data on alkaline phosphatase to validate the kinetic hypothesis.

2. The Grand Challenge: Levinthal’s Paradox

The Hook: How does a protein choose one unique structure out of a hyper-astronomical number of possibilities in a biological timeframe (seconds)?

Levinthal provides a “back-of-the-envelope” derivation to define the problem scope:

- Degrees of Freedom: A 150-amino acid protein has ~2,000 atoms. While physically constrained by planar peptide bonds, it still possesses ~450 degrees of freedom (300 rotations, 150 bond angles).

- The Combinatorial Explosion: Even with conservative estimates, this results in $10^{300}$ possible conformations.

- The Time Constraint: If a protein explored these sequentially (random search), even at maximum physical speed, it would require orders of magnitude longer than the age of the universe to fold. Yet, nature does it in seconds.

The Insight: The existence of folded proteins proves that random global search is impossible. The system must be guided.

3. The Core Argument: Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control

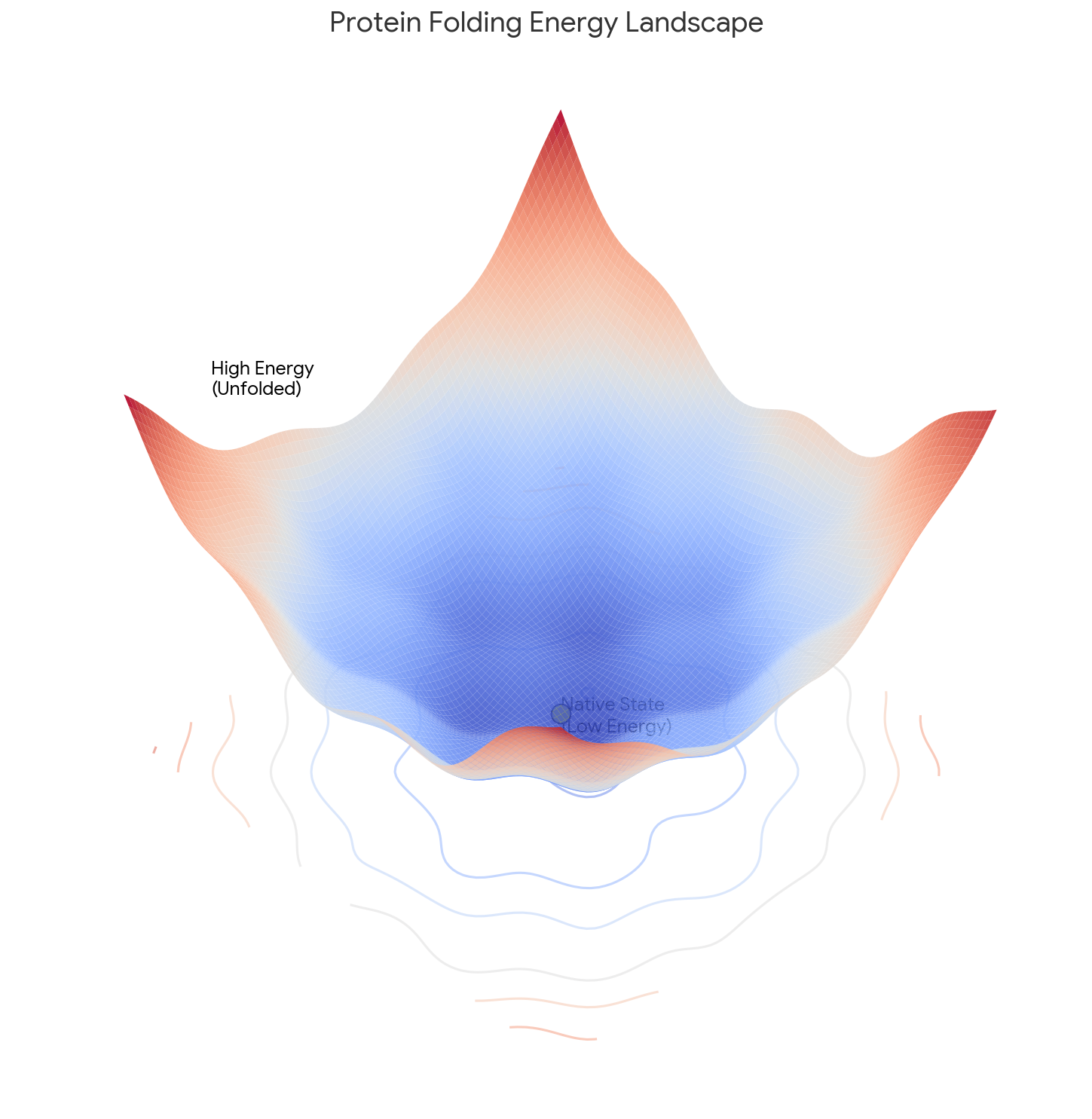

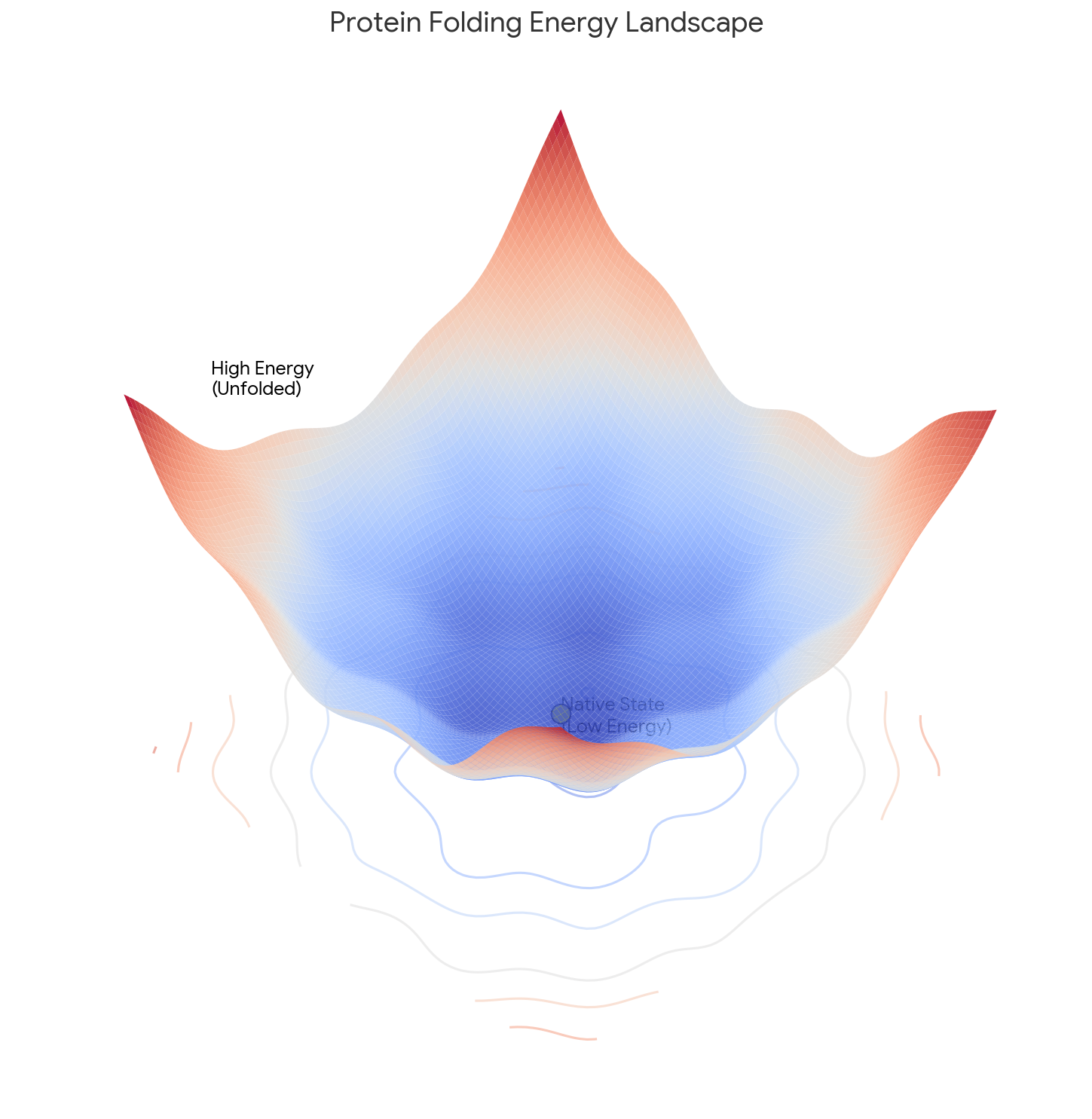

This is the central perspective contribution. Levinthal challenges the “logical assumption” that proteins fold by seeking the Global Minimum of Free Energy.

The Hypothesis: Pathway Dependence

Levinthal proposes that folding is under Kinetic Control:

- Nucleation: The process is “speeded and guided by the rapid formation of local interactions.”

- Pathway Constraints: These local interactions (likely within proximal amino acids) serve as nucleation points that restrict further folding, effectively pruning the search space.

- The “Metastable” State: The final structure is not necessarily the global energy minimum. It is simply a “metastable state” in a sufficiently deep energy well that is kinetically accessible via the folding pathway.

Experimental Validation

To support this “Pathway” argument, Levinthal cites work on Alkaline Phosphatase:

- Renaturation Window: The enzyme refolds optimally at $37^{\circ}C$ (biological temp) but poorly at higher/lower temps.

- Stability vs. Formation: Once folded, the enzyme is stable up to $90^{\circ}C$.

- Implication: If the native state were simply the global thermodynamic minimum, it should form spontaneously at any temperature where it is stable. The fact that it requires a specific temperature to form (but not to stay) proves that the pathway determines the outcome, not just the final energy landscape.

4. Connection to AI for Science

Understanding this paper is crucial for reading modern deep learning papers on protein folding (e.g., AlphaFold, ESMFold).

- Inductive Bias: Levinthal’s observation that “local interactions” guide folding is the biological justification for using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Attention mechanisms that prioritize local neighbor connectivity ($k$-nearest neighbors) in molecular representation learning.

- The Optimization Landscape: Levinthal’s rejection of “random search” prefigures the need for modern optimization techniques (like Gradient Descent) that navigate high-dimensional landscapes by following local gradients rather than brute force.

- Generative AI & The Manifold Hypothesis: Levinthal explicitly asks: “Is a unique folding necessary for any random 150-amino acid sequence?” and answers “Probably not.” This anticipates the core challenge of Inverse Folding (Protein Design). Most random sequences do not fold; valid proteins lie on a low-dimensional manifold. Generative models (like ProteinMPNN) are essentially trying to learn the boundaries of the “foldable” space that Levinthal first defined.